‘… without any consequence for the individual villains’

Mon. May 18, 2009Categories: Abstract Dynamics

At the European Business Ethics Network UK conference last month – at which I was lucky enough to be a keynote speaker (I will post up the presentation that I gave there very soon) – Campbell Jones gave a paper entitled “The Subject Supposed To Recycle”. In posing the question, who is the subject supposed to recycle? Campbell was denaturalising an imperative that is now so taken for granted that resisting it seems senseless, never mind unethical. Everyone is supposed to recycle; no-one, whatever their political persuasion, ought to resist this injunction. The demand that we recycle is precisely posited as a pre- or post-idelogical imperative; in other words, it is positioned in precisely the space where ideology always does its work.

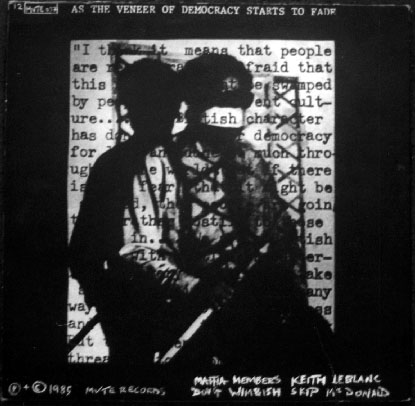

But the subject supposed to recycle, Campell argued, presupposed the structure not supposed to recycle: in making recycling the responsibility of ‘everyone’, structure contracts out its responsibility to consumers, by itself receding into invisibility. The discussion after Campbell’s paper turned on the question of agency – since “corporations are made up of individuals” doesn’t this mean that there is always hope for change? But it seems to me that “individual” is best defined as one incapable of acting. I would suggest that, at this time when the appeal to individual ethical responsibility has never been more clamorous – in her new book, Judith Butler Frames Of War uses the term “responsibilization” to refer to this phenomenon – it is necessary to wager instead on structure at its most totalizing. Instead of saying that everyone – i.e. every one – is responsible for climate change, we all have to do our bit, it would be better to say that no-one is, and that’s the very problem. The cause of eco-catastrophe is an impersonal structure which, even though it is capable of producing all manner of effects, is precisely not a subject capable of exercising responsibility. The required subject – a collective subject – does not exist, yet the crisis, like all the other global crises we’re now facing, demands that it be constructed. Yet the appeal to ethical immediacy that has been in place since at least 1985 – when the consensual sentimentality of Live Aid replaced the antagonism of the Miners Strike – permanently defers the emergence of such a subject.

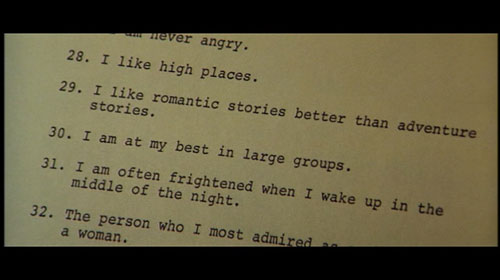

Similar issues were touched on in Armin Beverungen’s paper on The Parallax View. Armin saw Pakula’s film as providing a kind of diagram of the way in which a certain model of (business) ethics goes wrong. For The Parallax View is in a sense a meta-conspiracy film: a film not only about conspiracies but about the impotence of attempts to uncover them; or, much worse than that, about the way in which particular kinds of investigation feed the very conspiracies they intend to uncover.

The Parallax View came to my mind frequently when watching the Red Riding films, and all three could be seen as compulsions to repeat Pakula’s film. 1983‘s apparently redemptive coda might have constituted a failure of nerve, but 1974 and 1980 reiteratively traced the circuit of fatality which The Parallax View described with such grim elegance. It was perhaps 1974 – with its brutalist backdrops, and swaggering journo-rebel protagonist ultimately framed for the very crime he is investigating – that most echoed Pakula’s film (appropriately since 1974 was the year in which not only The Parallax View, but also The Conversation and Chinatown were released). Yet none of the Red Riding films achieved quite the satisfying horror that The Parallax View reached at its moment of bleak closure. It’s not only that the Beatty character is framed/killed for the crime he is investigating, neatly eliminating him and undermining his investigations with one pull of a corporate assassins trigger; it’s that, as Jameson noted in his commentary on the film in The Geopolitical Aesthetic his very tenacity, quasi-sociopathic individualism make him eminently frameable.

The terrifying climactic moment of The Parallax View* – the silhouette of Beatty’s anonymous assassin against migraine white space – for me now rhymes with the open door at the end of a very different film, The Truman Show. But where the door in the horizon opening onto black space at the end of Weir’s film connotes a break in a universe of total determinism, the nothingness on which existentialist freedom depends, The Parallax View‘s final “open door … opens onto a world conspiratorially organized and controlled as far as the eye can see” (Jameson). This anonymous figure with a rifle in a doorway is the closest we get to seeing the conspiracy (as) itself. The conspiracy in The Parallax View never gives any account of itself. It is never focalised through a single malign individual (compare, for instance, the grandstanding justification given by Richard Widmark’s hospital administrator at the end of Michael Crichton’s Coma, or even the opening scene of 1983, with pere-jouissance Bill Molloy holding court). Although presumably corporate, the interests and motives of the conspiracy in The Parallax View are never articulated (perhaps not even to or by those actually involved in it.) Who knows what the Parallax Corporation really wants? It is itself situated in the parallax between politics and economy; is it a commercial front for political interests, or is the whole machinery of government a front for it? It’s not clear if the Corporation really exists – more than that, it’s not clear if its aim is to pretend that it doesn’t exist, or to pretend that it does. As Jameson observes, what Pakula captures so well in The Parallax View is a particular kind of corporate affective tonality:

- For the agents of conspiracy, Sorge is a matter of smiling confidence, and the preoccupation is not personal but corporate, concern for the vitality of the network or the institution, a disembodied distraction or inattentiveness engaging the absent space of the collective organization itself without the clumsy conjectures that sap the energies of the victims. These people know, and are therefore able to invest their presence as characters in an intense yet complacent attention whose centre of gravity is elsewhere: a rapt intentness which is at the same time disinterest. Yet this very different type of concern, equally depersonalised, carries its own specific anxiety with it, as it were unconsciously and corporately, without any consequences for the individual villains.

… without any consequences for the individual villains… How that phrase resonates just now – after Hillsborough (whose grisly catalogue of police incompetence, malice and mendacity was exhumed again recently because of the twenty year anniversary), after Jean Charles De Menezes, after Ian Tomlinson, after the banking fiasco. And what Jameson is describing here is the mortifying cocoon of corporate structure – which deadens as it protects, which hollows out, absents, the manager, ensures that their attention is always displaced, ensures that they cannot listen. The haunting power of David Morrissey’s rendering of Maurice Jobson in the Red Riding films came from the way that he caught that abstracted corrupt/ corporate blankness just so. The delusion that many who enter into management with high hopes is precisely that they, the individual, can change things, that they will not repeat what their managers had done, that things will be different this time; but watch someone step up into management and it’s usually not very long before the grey petfification of power starts to subsume them. It’s here that structure is palpable – you can practically see it taking people over, hear its deadened/ deadening judgements speaking through them. And surely we have all felt the effects of structure whenever we assume a so-called position of responsibility: we immediately find ourselves second-guessing our responses, anxiously concerned about whether we are doing what It wants, never sure if we are measuring up…

But we shouldn’t rush to impose the individual ethical responsibility that the corporate structure deflects. This is the temptation of the ethical which, as Zizek suggested at the Birkbeck Communism conference, the system is using in order to protect itself – the blame will be put on supposedly pathological individuals, those ‘abusing the system’ (and then deflected onto other targets altogether) rather than the system itself. But the evasion is actually a two-step procedure – since structure will often be invoked (either implicitly or openly) precisely at the point when there is the possibility of corporate individuals being punished. At this point, suddenly, the causes of abuse or atrocity are so systemic, so diffuse, that no individual can be held responsible. And now we are back at Hillsborough and the Jean Charles De Menezes farce, with the individual policemen walking free. But this impasse – it is only individuals that can be held ethically responsible for actions, and yet the cause of these abuses and errors was corporate, systemic – is not only a dissimulation: it precisely indicates what is lacking in capitalism. What agencies are capable of regulating and controlling impersonal structures? How is it possible to chastise a corporate structure? Yes, corporations can legally be treated as individuals – but the problem is that corporations, whilst certainly entities, are not like individual humans, and any analogy between punishing corporations and punishing individuals will therefore necessarily be poor. And it is not as if corporations are the deep-level agents behind everything; they are themselves constrained by/ expressions of the ultimate cause-that-is-not-a-subject – capital.

Let’s be in no doubt. There are certainly conspiracies. I’ve been a victim of one in the workplace (1980 made for uncomfortable viewing, not least at the moment of reversal when Hunter, the man charged with investigating corruption, suddenly finds himself the object of a counter-investigation – but at least I only lost my job, I didn’t get my house burned down or get shot, for which I suppose I should be grateful). But the issue with conspiracies under capitalism is: does anyone really think it would be better if we replaced the whole managerial and banking class with a whole new set of (‘better’) people? Surely it is evident that the vices are engendered by the structure, which is one reason that Marxism is preferable to any moral critiques of capitalism. We also need to ask how it is that particular conspiracies can be successful. Current conditions favour conspiracy – as Nick Davies shows in Flat Earth News the media, rather than uncovering conspiracy (as mythologised in Pakula’s All The President’s Men), now tend instead to obediently propagate whatever PR hype they are fed. Which is why we should take a step back and ponder why it is at this precise moment that the stories about MPs’ expenses have emerged. M John Harrison suggests that the ‘uncovering’ of the irregularities in MPs’ expenses is not the result of intrepid investigative reporting, but is a (successful) attempt at news management: cover-up in the guise of revelation.

- The bankers stole our money: but the MPs have stolen the taxpayers money. Instant uproar.

The bankers stole more. They didnt fiddle a meagre £10,000 here & there. They got away, personally, with fortunes. They didnt fiddle a mortgage; they fiddled millions of mortgages & then collected £7 or £8 million in pensions as their price for leaving the institutions they had wrecked.

They got the taxpayer to pay them to go. How is that not stealing the taxpayers money ?

Paying MPs is a form of public spending. When we are stupid enough to vote the Tories back in, our rage against MPs will be redirected by them on to every other form of public spending. The bankers will get away with it. The blow that should have fallen on them will be received instead by a handful of hapless prats who got their fingers in the petty cash. Result.

Our frustration with the bankers, our rage against the recession they caused, will be refocussed on that arch enemy of Toryism, public spending. Because MPs have been shown to be corrupt, all public services will be blackened by association, then cut: it will seem perfectly logical. The disadvantaged, their ranks swelled by hundreds of thousands of victims of the bankers, will be punished for the sins of the advantaged. As usual, ordinary people will be deftly turned into their own enemies. Fantastically elegant politics.

Charlie Brooker’s Newswipe has shown how Downing Street and the tabloids choreograph particular stories, so that the newspaper ‘outrage’ is factored in from the start. Like Adam Curtis, Brooker has also been dogged in identifying the way in which emotionalised and personalised content increasingly displaces news in the old sense. Bleary sentimentalism blocks any thinking about real abstractions; except when those abstractions are wheeled on as a mystified exculpation in the form of the global economy, which appears to be as sublime, mysterious and incomprensible as any theological entity, and less susceptible to human will than even the weather.

*(The climax of The Parallax View is available on online, but the clip can’t be embedded, so you’ll have to go YouTube to see it.)

__________________________________________________________________

Incidentally, while we’re (back) on Red Riding… I’ve been meaning to link to this excellent Fantastic Journal post for ages now. FJ draws out what I most appreciated in the Red Riding films: their “specifically visual intelligence”.