Traps and cats

Mon. March 19, 2007Categories: Abstract Dynamics

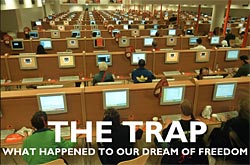

There’s nothing very surprising in Adam Curtis’ The Trap: What happened to our dreams of Freedom, compelling as it is. Judging by the second episode (I missed the first one last week), The Trap might as well be called A Brief History of Neo-Liberalism. Using his trademark oneiric style, Curtis shows how the spread of reductive models of human motivation from the Cold War into economics, education and science led to the occlusion of politics. This week, Curtis concentrated on New Labour, demonstrating how the Blairites’ fixation on targets and quantification of the unquantifiable led not to increased efficiency of public services, but what I have called ‘market stalinism’. Curtis’ detailing of the way in which harrassed managers ‘game the system’ – cutting waiting times in casualty by employing nurses whose only job was to say ‘hello’ to patients, or re-classifying trolleys as beds – made for a bitter comedy, whose punchline is the fact that social mobility has actually declined under a Labour government.

Ironically, as Bat complained in his review, The Trap performs its own occlusion of politics. ‘There is no sense of any kind of alternative vision, nor any pointers to a solution. Episodes such as the rise of Margaret Thatcher just “happen”, with the immense political conflicts of that period relegated to a footnote. Rather than seeing ideas as being consciously promoted by particular social forces, Curtis paints a world where we all just sleepwalk into oblivion.’

What that is left out of The Trap – struggles, contestation, alternatives – is covered in Marker’s A Grin Without a Cat, which Kino Fist will be showing next week. I wrote the following about A Grin Without a Cat last year:

- The revolutions were cultural; which is to say, they understood that culture and politics could not be conceived in isolation from one another. Both Althusser and the situationist-inspired students of 68, in many ways so opposed, could agree on at least one thing: that cultural products were never merely cultural. In their condemnations of recuperated Spectacle and Ideological Apparatuses, they granted a weight to cultural products which few would countenance now.

… ‘which few would countenance now’… An observation that, sadly, is confirmed by the comments thread on this post of Daniel’s, where the idea that ‘entertainment’ could have any political implication is considered so self-evidently ridiculous that anyone holding it must be ‘sexually inadequate’. This, mind you, is in relation to 300, a film described by Ahmad Sadri as follows:

- Nobody expects historical accuracy from a Hollywood movie based on a graphic novel. But using domestic racial and sexual stereotypes to demonize the enemy is breaking new ground. In the movie 300 Persian immortal knights are snarling beasts beneath their sinister masks and their king is a pierced and bejeweled androgynous savage. But, more significantly, Snyders Persians I am not talking about the disposable extras covered up to their eyes in male burqas are predominantly black and by implication of mannerism and affect, homosexual. Allowing the widest berth for the genre and medium one still marvels at Snyders audacity in demonizing the Asiatic hordes while morphing the Spartan warrior into the typical white American survivalist. Snyders Spartans are white guys fighting a sea of racially inferior blacks, yellows and browns. They are staunchly heterosexual and weary of their elected elders (ephors) who are seen as sacrilegious lepers, traitors and scheming politicians.

If it is regarded as an absurd stretch to find political meaning in a film like this, what hope is there? This, assuredly, is the militantly complacent view from inside the entertainment-opiated Trap.

The accusations of ‘sexual inadequacy’ are particularly telling. Perhaps we need to reverse this; it is not that political awareness is a symptom of sexual inadequacy, but quietism that is a symptom of hedonic satiation.