To the centre of the city…

Sun. January 8, 2006Categories: Abstract Dynamics

|  |

‘You could feel something lurking in Luton, in the concrete, the brickwork, under the bridges, in the parks. It wasn’t supernatural, it wasn’t anything that would jump out of the dark pockets and grab you. It was more subtle, like the gradual onset of Alzheimer’s. The muggings, race hatred, beatings, car crashes, suicides were just symptoms. Nobody wanted to be around when the disease suddenly accelerated and marched right over our heads’

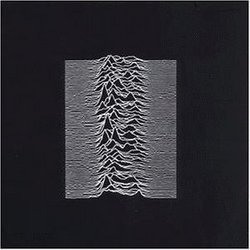

Brilliant post by Martin Beyond the Implode, ostensibly about listening to Joy Division in Luton. It tells you more about Unknown Pleasures than a thousand marks-out-of-ten, listen-to-the-nimble-basslines review could ever hope to; and more about what it is like to live in smalltown England than any Granta-type Eng Lit. essay. Here it is, the existential geography of Joy Division, those between-child-and-adulthood interzones and sub-urban shadowplaces seen from behind the windscreen of a car going nowhere, forever.

‘You know you’re in a fucked area when the KFC imitators loom large – Dallas Fried Chicken, where you can’t differentiate between backside and beak, never mind between Halal, Kosher or Carcinogenic. So, we used to drive around all night. Hockwell Ring, Marsh Farm, Bury Park, Lewsey Farm, Wardown Park, Stopsley. And then sometimes out into the backwater villages, looking for signs of life.’

Where do you find this England? Hardly ever in films (you have to think back long ago, long before cinema lost contact with an England that wasn’t either Gangsta Sexy or Notting Hill prim, to something like Sidney Lumet’s The Offence for anything that summoned this sodium-lit hell); rarely in novels (even Ballard is in some ways too poetic; David Peace captures it better, not so much in physical descriptions, but in the pinched dialogue and claustrophobic, alcohol-fugged thought patterns of characters-as-environment). But it was everywhere in postpunk (not surprising that postpunk is a massive influence on Peace), in every note of Cabaret Voltaire, The Fall, PiL, Magazine, TG, Foxx’s Ultravox, Tubeway Army, the Banshees, Alternative TV. (Part of the reason that postpunk pasticheurs like Franz Ferdinand and The Editors will only ever produce tracings that leave no trace is that they confront only the stylings and the forms, not the mushroom clouds and the piss-stenching alleyways that gave rise to those styles and forms.) In mourning and mocking the Trad Britannia of Empire and tea dance, of music hall and lazy Sunday afternoons, British Pop of the Sixties was still in thrall to Pathe nostalgia; postpunk saw through all that, looked headlong at the Concrete Island, ‘the brickwork illuminated by 1,000 watt tungsten, the crowbar scuff marks across the doors of the ground and first floor flats, the intersections where the concrete turned to pungent yellow grass and the signs pointed’….

What is most draining about this landscape is its banality (decline can have poetry and magnificence; but retail parks and burger parades of the average cloned British high street are like garish grey stains, repelling all attempts at sublimation). And, as Lyotard observed in Libidinal Economy – ‘they loved their annoymous pubs’ – there is something willed about that banality, as if these jaded vistas expressed the replicant desires, the electric dreams, of the first country to host Kapital.