The outside of everything, now

Sun. May 1, 2005Categories: Abstract Dynamics

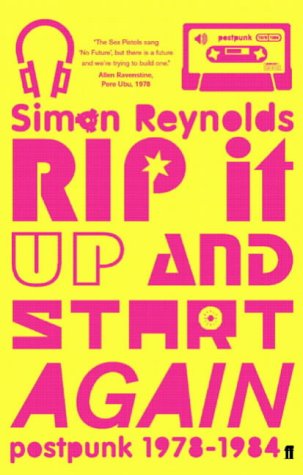

A week dominated in every way by Rip It Up and Start Again, and rightly so.

Perhaps the best tribute you can pay to the book is that it makes you positively look forward to train and bus delays, to any moment when you can return to feed the hunger, scratch the itch ….

The size of the crowd at the Boogaloo event on Wednesday, but, more than that, a certain sense of ferment in the atmosphere, testified to the fact that this is something more than a book. Stirring up the ghost of postpunk cannot but be an act, an intervention in cultural politics – since postpunk not only judges contemporary pop culture (harshly), it brings back the legitimacy, the necessity of being judgemental, of having some criteria (non-musical criteria, non-hedonic criteria) for enjoyment. Such a position is not repressed by contemporary pop culture (=the cultural logic of late capitalism), it is made unthinkable by it.

Something in Paul Morley certainly seemed to wake up on Wednesday. (And something in us?….)

A certain Morley was knowingly complicit in the termination of postpunk – as Simon wryly reminded him when, after Morley had fulminated against the facile notion that the worth of a pop record is determined by its popularity, he asked him: ‘but didn’t that idea come from you?’ It’s not accidental that, grotesquely but inevitably, Morley’s early eighties Pop(ul)ist stance should have inspired some NME readers to turn towards neo-conservatism. In retrospect, it’s possible to see the turn to Popism as the beginning of a giving voice to a creeping disappointment which spread slowly, insidiously yet incrementally during the period until almost everything of postpunk – even the traces – was disappeared (in the way that political prisoners are). The disappearing trick was almost complete when the Pod-Zombie duplicates started to arrive a few years ago, formally perfect copies mass-produced by kapital.

It’s easier to see now than it was at the time the extent to which the cultural artifiacts – and the discourse surrounding them – produced in the wake of postpunk were being programmed by resurgent Kapital. A certain notion of realism began not only to prescribe what could now happen, but to airbrush out what had actually happened. The idea that pop could be more than a pleasant divertissement in the form of an easily consumable commodity, the idea that popular culture could play host to concepts that were difficult and demanding: it wasn’t sufficient to disavow these possibilities, they must also be denied. Operation Amnesia, Pacification Program: it never happened did it, it was a delusion, a folly of youth, and we’re all grown up now….

Naturally, Morley’s railing against amateurism, his advocacy of ambition and lushness, play rather differently in 2005 than they did in the early 80, but that’s only fitting, since his manifestos-as-works-of-art-in-themselves were produced as strategic provocations rather than timeless aesthetic philosophies. Even though the Morley of the disappointing Words and Music claimed 00s web Popists as his offspring, it’s hard to imagine the Morley and Penman of 1981 being gratified by the thought that their legacy would be the de-conceptualization and de-politicizing – i.e. the consumerization – of Pop. They could scarcely have imagined, then, the way in which Pop would de-speed over the next twenty years, that their embrace of Entryism would prove to be the last word in rough-and-tumble theoretical dialogue that seemed, then, as if it could go on forever.

Reading Rip it Up is like re-living my early Pop life – but now at a distance, like Spider in Cronenberg’s film, an adult at the corner of the screen watching himself as a child. With Simon as my Virgil through that Paradiso lost, I can now recognize that Pop for me was postpunk – Kings of the Wild Frontier was the first LP I bought and ABC were the first group I saw live. But Rip It Up makes me cognizant of what I, growing up absurd into postpunk, couldn’t have appreciated at the time: that the richness of Pop then – not only sonically, but also in terms of concepts, clothes, images – lasted only a relatively short period, made possible by specific historical contingencies.

Nevertheless, expectations were raised in me, and more or less everything I’ve written or participated in has been in some sense an attempt to keep fidelity with the postpunk event. Cyberpunk – both in its restricted literary generic sense and in the broader sense we have given to it in ccru – was up to its neck in postpunk. Gibson’s debt to Steely Dan and the Velvet Underground has long been acknowledged, but the dominant tone of Neuromancer was an overhang from postpunk. Gibson named his high-tech prostitutes after the Meat Puppets, but Neuromancer’s technihilistic ambience, dub apocalypticism, amphetamine-burned-out Cases and hectic, twitching finger-on-fastforward and comatone-cut-out narrative, seem to be transposed straight out of the British postpunk scene.

One of the things that is most remarkable about postpunk, actually, is its near total erasure of America and Americanness. When I was in my early teens, the only American pop you’d hear that wasn’t disco would be encountered while trudging round the shops on Saturday afternoon, as Paul Gambacini’s Hot 100 was broadcast over the store PAs, and it was a window into a horrifyingly deprived world of barely imaginable banality.

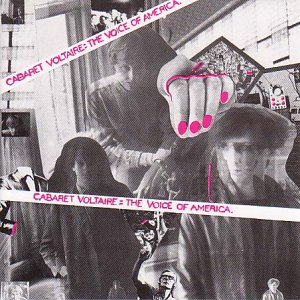

Of the few American groups of any significance in this period, perhaps only Devo and the Meat Puppets took much inspiration from the American landscape (in Devo’s case of course, the US was processed as a thoroughly aritificial PKD-US-trash heap of post-industrial detritus). No Wave emerged from the rootless cosmopolitanism and transnational nihilism of New York, while in many ways the most interesting American groups – Tuxedomoon and the Residents – were Europhiles. In postpunk, America increasingly featured as a series of ethnographic traces – as in the ecstatic, hysterical and authoritarian ghost chatter of Amerikkkan TV and media flittering through Cabaret Voltaire’s Voice of America or Byrne and Eno’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts.

It’s hard to remember now, but in the period after Vietnam and before the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, America was a paranoid and enfeebled nation, Nixon-sickened and introspective, scared of its own shadows. Postpunk was there to witness – and mock – the seeming absurdity of the idiot actor Reagan being wheeled on to give America’s confidence a shot-in-the-arm, although initially, even Reagan’s rise to power seemed to be a kind of sinister postpunk prank, since it made eerily real what had been predicted by one of perhaps postpunk’s most important influence, Ballard. (In the States, Ballard’s Atrocity Exhibition was re-titled Love and Napalm: Export USA, and that novel – so omnipresent in postpunk production – was a kind of simultaneous observation of the way in which Britain was being turned into an LA of ubiquitous advertising hoardings as well as a British view of the US.) By the time that postpunk went out in a neon-blaze of irony-tainted glory on MTV, the joke had, to say the least, worn thin. Pop had gone Blue-Gene American rock, again (I still remember the barely comprending horror I felt when the NME started to give covers to the t-shirt and jean-clad Springsteen; worse was to follow, with the likes of The Long Ryders). Boredom was back, but this time, without the punks to denounce it. The arid shopping mall at the end of history opened up as the only possible future. Worse than the career opportunities that never knocked were the ones that did: jobs for everyone in the striplit wall-to-wall mart of ‘Time Out of Joint’ America in which it is 1955, forever…. No shadows to hide in…. No room to move, no room to doubt….

Ironic in some ways that Rip it Up should be named after an Orange Juice song, since Orange Juice and Postcard were responsible for what was in many ways a British equivalent of Springsteen’s US return-to-roots. If the comparison seems strained, think about the way in which both Springsteen and Orange Juice self-consciously advocated a kind of locally-rooted authenticity defined by its rejection of artificiality. For Springsteen’s reich and roll uniform of denim, substitute OJ’s Brideshead Revisited sweaters. Like the Smiths, the Postcard-era Orange Juice retrospectively imagined a British Pop-that-never-was. The Brit equivalent of American open-throated stridency was a kind of floppy-fringed, tongue-tied dithering that was just as much of a self-conscious reclaiming of signifiers of national identity as Springsteen’s passional working stiff poses were. (Is it too fanciful to hear in the early Orange Juice an anticipation of Hugh Grant’s unbearable foppery and faffing?)

By the time I got to University in 1986, Orange Juice, and the Smiths, had achieved hegemonic control of the undergraduate ‘imagination’. It was perfect Pop for young men who were destined to go on to careers in marketing but who liked to think of themselves as ‘sensitive’.

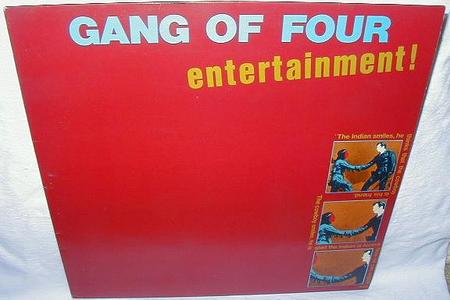

Orange Juice also played in a major part in rehabilitating the love song. If romance featured in postpunk at all, it was as something to be derided and demystified (as in the Slits’ ‘Love Und Romance’ or Gang of 4’s ‘Love Like Anthrax’) or as something to be politically and theoretically interrogated a la Scritti or Devoto. The renewed preoccupation with love was a re-occupation of ‘the ordinary’, a re-statement of a revivified humanist confidence in a dehistoricised continuity of ‘things that go on the same’.

It’s often said that punk was what Britain had instead of ’68, but that in many ways fails to process how punk had surpassed the events in Paris. ’68 was as much a rejection of certain theoretical positions as it was of the institutions of modern liberal society so that, in the conflagration of the Sixties ‘Desirevolution’, the cold Spinozism of Althusser’s structural analysis was burned down with the buildings. Punk and postpunk, however, were profoundly suspicious of the Dionysisan triumvurate of leisure, pleasure and intoxication, so that the required attitude was one of vigilant hyper-rationalism, a kind of popularized Althusserianism in which interiority was exposed as an ideological bluff, and emotions were understood not as ‘real expressions of authentic subjectivity’ but as structurally engineered reactive circuitries. The stance such a perception demanded – and this was a culture that was deliberately and unashamedly demanding – was one of ‘proletarian discipline’ rather than slack indulgence, its puritanism recalling the egalitarian social ambitions of the original Puritans. In this respect, Scritti’s move from pleasure-repudiating Marxism to ‘playful’ deconstruction is enblematic of the way in which the decade would develop, in universitities as much as in the charts. The exorbitant surfaces of Cupid and Psyche‘s might have eschewed interiority but at the same time their simulations of interiority were no less authentic, no less soulful, than other versions of interiority purveyed by more credulous, non-ironic sources in the mainstream. The person being duped now was the Green who imagined that his intelligence would prevent full incorporation.

But the triumphant capitalism Green was already working for had no trouble at all in consuming those who sought entry into it. In the 70s, in an effort to dispel the notion that there were ‘subversive regions’ that would be inherently indigestible for capital, Lyotard compared capitalism to a ‘Tungsten-carbide stomach’ that could consume anything in its path. By the 80s, as Jameson has observed, Kapital had become a gigantic interiority without any outside: a kind of jaded pleasuredome reminiscent of the all-encompassing bubble environments imagined in 70s SF. Except it looked, for all the world, just like a familiar domestic environment: the nice house, nice family set-up ridiculed by Jamie Reid, now refurbished with added ironic distantiation and hooked up to 24 hour MTV. What had been lost was the ‘glam knowledge’ that first entered Pop through Pop Art: that the social scene is a stage set populated by puppets cornfed cheap dreams and sedated by narcotics of every kind. The punks knew they were replicants; that everything that seemed to be inside was bio-psycho-social machinery that should be re-programmed or stripped out. The end of punk was the forgetting that the memories were false, that the domestic scene was so much pasteboard and image virus.

At the time of postpunk, Pop could still be a counter-cultural lab (endlessly raided by, but never subordinated to the diktats of, Kapital). It really is not clear whether Pop could be that again. Someone asked the panel on Wednesday if dredging postpunk up was an exercise in nostalgia. But this is entirely to miss the point of Jameson’s critique of the nostalgia mode. For Jameson, the nostalgia mode is exemplified by cultural artifiacts which deny, or more radically, are unaware of their own total debt to the past. In other words, being contemporary does not guarantee being modern, especially not in a postmodern culture whose temporality is obsessively citational and commemorational. One of the most idiotic tics in cultural gatekeeping today is its need to justify the past in terms of the present: as if Gang of 4 were only significant because they ‘influenced’ no-mark, here today-boot sale tomorrow clones like Bloc Party and Franz Ferdinand. As if simply being here, now, meant that something New and Important is happening…

Pop could function differently in postpunk because, at that time, it was the space which most readily leant itself to the production of a counter-consensual collectivity. Postpunk was an awakening from Kapital’s ‘consensual hallucination’, a means of channeling, externalizing and propagating disquiet and discrepancy. It provided a crack in the way the social represented itself; or rather, exposed that crack. What the social would have us believe is dysfunction, grumbling, failure suddenly became the sound of the ‘outside of everything’. Records, interviews, the music press, were the means by which contact could be made between affects, concepts, commitments that would previously have been locked into private space.

Some of the panel last Wednesday were unsure if they had really done anything, if their dreams of doing something more than simply entertaining were anything more than youthful naivete, understandable then, an embarrassment now. But the achievements of postpunk can be appreciated, negatively, in what culture now lacks. Go into a roomful of teenagers and look at their self-scarred arms, the anti-depressants that sedate them, the quiet desperation in their eyes. They literally do not know what it is they are missing. What they don’t have is what postpunk provided… A way out… and a reason to get out….

So is this a counsel of despair?

Not at all.

There are new means for producing counter-consensual collectivity.

Like this.

The web has a distributional reach, a global instaneity, whose unprecedented scale is easy to take for granted. But its vast potential far outstrips anything that fanzines or records could have achieved in the 70s. What needs to happen is a kind of ‘existential reframing’: to see what happens here not as Kapital wants us to see it, as ‘failed’ writers resentfully carving out some insignificant niche because they can’t ‘make it’ in the overlit interior. The logic of Kapital insists that anything that is not reproducing it, or serving such a reproduction, is a waste of time. But to reframe what is happening would be to radically reverse these idiotic priorities. And the continuing relevance of postpunk is to remind us that such reversals are possible, to provide the impetus for the development of a (punk) will to retake the present….