The gaze of the object

Sun. September 25, 2005Categories: Abstract Dynamics

Well, the Kate Moss post I had promised and planned has been somewhat overtaken by events, but it’s worth observing that the affair has brought forth a near-inventory of Lacanian themes.

The politics of enjoyment

The ‘scandal’, such as it is, clearly centres upon enjoyment: she has it, whereas ‘we’ – the interpellated subjects of the tabloid stories – are denied it. The British tabloid press has long understood the appeal of stories that play upon readers’ resentment of Those Others who Enjoy (such stories are especially popular if the Enjoyment is seen to be at ‘our’ expense). The fantasy space that the lurid ‘revelations’ about lesbian orgies and ‘fist-sized’ balls of intoxicants opens up is that of an impossible, obscene, total enjoyment, an enjoyment which is only possible for Others (there are innumerable, supposedly contingent, reasons why we don’t have access to Total Enjoyment, but they, they revel in it…) At a certain point, the moral condemnation of obscene luxury inevitably gives way to an acknowledgement that Total Enjoyment was not, in fact, possible, as ‘irresponsible hedonism’ becomes ‘My Cocaine Hell’. The resentment of enjoyment is only sated once this final stage is reached, and it is satisfied that the enjoyment was not there to be had in the first place.

The big Other must not see all

There can be no-one who was shocked or even slightly surprised by the ‘revelations’ about Moss. Model takes cocaine… Next….

But we will be missing one of the lessons that the Moss affair has to teach if we simply sigh and move on, since nothing could more clearly exemplify how the the big Other functions in contemporary culture than the way in which Moss has been treated. Zizek has tirelessly insisted that we are liable to overlook the importance of the enormous difference between what is known universally (but secretly) and what is known officially. Terrible consequences always ensue once unacknowledged, obscene popular knowledge crosses over into the official culture. The big Other resides in the distinction between our all knowing something and it being publicly acknowledged, so when something that was once universally known is actually publicly ‘revealed’, the big Other must act. Or, better (given that the big Other doesn’t exist, except as a retrospeculative fiction), officials feel that they must act on the big Other’s behalf. As a perfect example of the latter phenomenon, witness the now almost completely discredited Ian Blair’s ludicrous pronouncements about the Met considering action against Moss because of ‘the possible effect on impressionable young people’. ‘Impressionable young people’ is of course one of the names of the big Other, one of whose crucial features is that it cannot know all. We might all know that models and celebrities routinely use class A drugs, but the big Other remains does not know. Those who rightly condemn Blair’s intervention on the grounds that his stance implies that it was perfectly acceptable for Moss to snort cocaine anywhere except on the front pages of the tabloids must at the same time recognize that it is not the commissioner of the Metropolitan Police who has invented this bizarre situation: PR, advertising, the judicial system, politics, all depend on the highly artificial but routinely functional distinction between obscene and official knowlege. What Deleuze calls an ‘incorporeal transformation’ happens when events are reported in the press: the exact same occurrence becomes something of quite another nature.

The gaze of the object

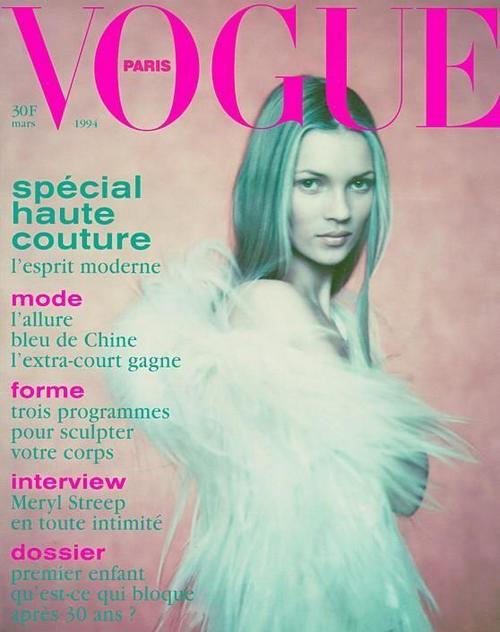

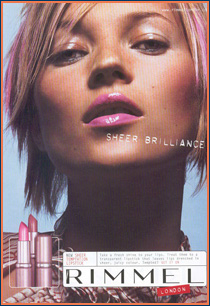

My original topic, what I wanted to address before the scandal broke, was Moss’s appeal. In what does it reside? A useful article in the Guardian earlier this year by Joanna Briscoe provides some clues. ‘Women – perhaps even more than men – are intrigued’ by Moss, Briscoe observes. Part of the attraction for women is the very ‘naughtiness’ that now sees her castigated (Moss ‘manages to embrace the middle ground between self-destruction and steely control’), part is the whiff of the vernacular that no amount of cosmetics and lighting can extirpate from her features. Briscoe writes that Moss’s ‘paradoxical, multi-faceted appeal means that in the post-Benetton age, the faintly Asian cast of Moss’s features translates into internationally comprehensible beauty, yet she is deeply English, to a degree that makes the icons of the 60s – Jagger, Twiggy, Faithfull – her only true antecedents, for all the posturing of Britpop. While contemporaries such as Kate Beckinsale or Minnie Driver undergo LA makeovers to secure global appeal, Moss trails the whiff of the Croydon comp, of Primrose Hill hedonism, of NHS teeth and pure, dirty London.’

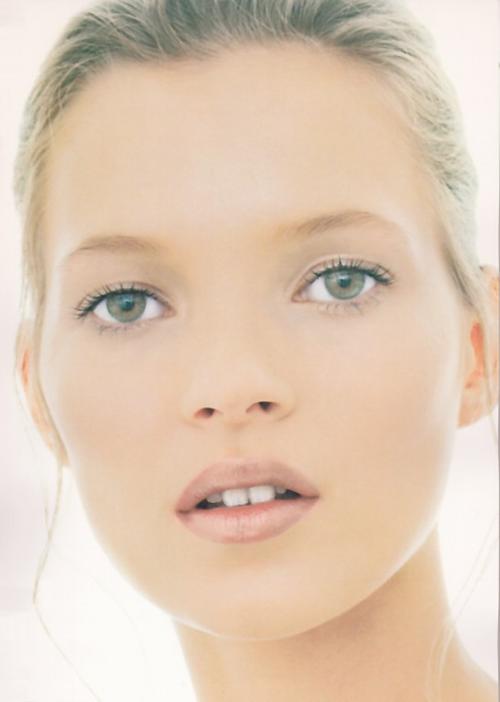

Yes, Moss certainly has an ineradicable flavour of the quotidian about her, but that only deepens the mystery of her appeal. What is it that makes her more than just an ordinary London woman with unusual looks?

The model’s task is to transform herself into images of the Sublime, to attain what Lacan calls the ‘dignity of the Thing’. Now more than ever, the Sublime cannot be confused with the Ideal. Once it may have been possible to produce a sustainable image of the Ideal by covering up, maintaining a certain distance, but the intrusive nature of contemporary media make Idealization impossible; it isn’t long before a photograph or an ex-lover appear to shatter the illusion. Moss’s allure has not therefore depended on cultivating an impossible inviolability; on the contrary, as Briscoe writes, she is ‘more often snapped fag in hand, screwing up pisshole eyes to take a drag on a London street, than posing on a red carpet’. The drugs stories might have destroyed her career, but they have had little impact on her allure. That’s because Moss has managed to capture the inherently elusive qualities of the objet petit a itself, that which can never be possessed or caught. The important thing to remember, however, is that the object petit a is transcendentally, rather than empirically, inaccessible (much as we fantasize that the blocks to attaining the object are always merely contigent, ‘if only X or Y had not happened, I would really have had it’). Moss’s photographs manage to suggest that, even if you ‘had’ her sexually, that would not be ‘it’, there would still be something in her that will always lie beyond reach, no matter what.

Perhaps this is part of the reason why Moss has never been a Lad’s favourite. The melancholy of Lads’ relationship to pornography consists in its duped literalism – ‘what I really want from women is their image, and what I really want from their image is to ejaculate’, therefore I might as well wank over pictures. What this misses is the fact that there is no ‘thing’ that is ‘really wanted’.

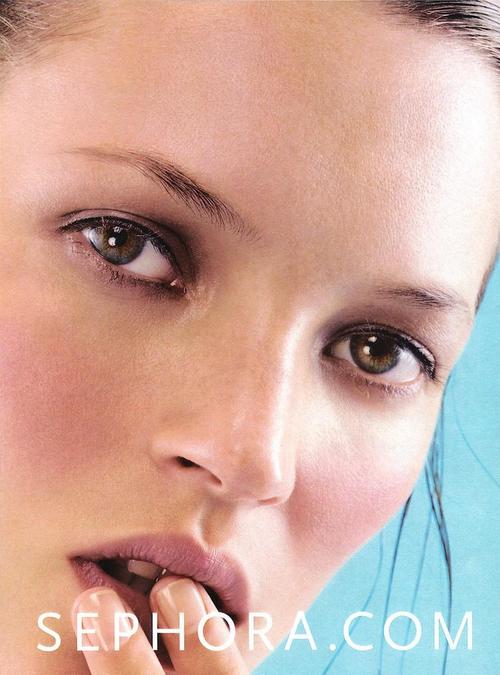

How a model looks is not even half the story; how she looks at the camera is where her artistry lies. The art of so-called glamour modelling consists not so much in entrancing the male eye so much as placating the male ego. That is why such photography has little to do with the dizzying sorcery of glamour (to ‘glamour’ originally meant to cast a spell on men, often to make them impotent) and trades instead on girl next-door homeliness, the slightly tantalizing appeal of the nearly-available. Crucially, the models’ come hither looks are designed to make the male viewer feel desirable. (Hence Zizek’s point that it is the users of pornography who are its real objects; the subjects are those who stir and manipulate desire, the actors and models themselves.)

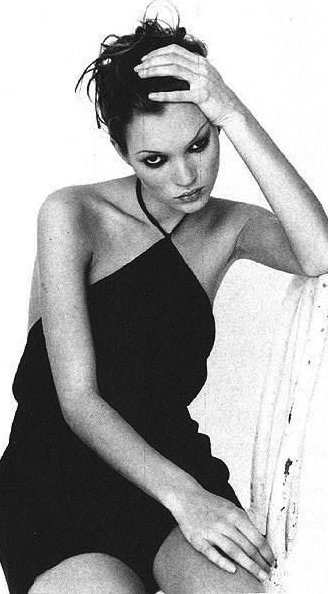

I suspect that Moss is so appealing to women largely because she refuses to give that look. She is not there to make the viewer of her image feel comfortable, still less desirable or interesting. The glamour model either looks to camera smoulderingly or gives the impression of being demurely caught unawares. Moss does neither. She always radiates an easy awareness that she is being photographed, but doesn’t seem especially interested in who is seeing her or the fact that she is seen. Her particular art is the cultivation of a look to camera that verges on the disdainful and the contemptuous, but never amounts to outright confrontation. It is almost as if she is fully aware of the camera (and therefore of us) but that, even when she looks directly at ‘us’, she looks through us, past us, fixating on something just over our shoulders. The challenge this poses is no longer the shock of the object talking, as it was with Grace Jones, because Moss, famously, does not speak.

In Moss’s case, not speaking does not connote a failure to be a subject. No: it connotes a confident embracing of the role of the object. Moss doesn’t talk back, she looks back, confirming the validity of Lacan’s dictum that the gaze is on the side of the object. Lacan was referring to that uncanny sense that objects watch us (the converse of the fact that the petit objet a is a screen for our projections is the sense that beyond the screens, the Real looks back, acquiring all the animation that we have lost). Moss’s gaze suggests that it is not the empowerment of the subject that is the real goal we pursue, but the Sublime serenity of objecthood. To be pored over, stared at, and to look back, not in anger, but with something approaching indifference ….. what could be better than that?