SELLING ENGLISHNESS FOR THE DOLLAR (SLIGHT RETURN)

Mon. October 13, 2003Categories: Abstract Dynamics

|

|

|

It’s back – thanks to perfect angel, Mr Michael Carr. Sadly the comments are unrecoverable.

Well, we agree on one thing. Gabriel’s ‘Sledgehammer’ was the end of something. But of what, precisely?

If I was to date the utter end of “the Sixties” in music terms to a single record it might be Peter Gabriel’s “Sledgehammer”. Those albums around “Games Without Frontier” and “Shock The Money” were his “postpunk” efforts (paranoia, alienation, no cymbals on the drums). “Sledgehammer” is him selling out to the Eighties, that burnished airless Go West beige-funk sound.

Is there a record more emblematic of the Eighties – the post 82 80s, the post postpunk 80s – than that ? The bright and breezy, brassy, stodgy Eighties ‘Soul’ sound – horribly like Go West – that awful, played-every-five-minutes, conspicuously Expensive video…. It’s like being trapped in a shopping mall on Saturday afternoon. Forever.

In an interesting post on House at World’s End , Robin Carmody develops Simon’s argument, pointing out that ” ‘Sledgehammer’ and ‘Invisible Touch’ were consecutive US No1’s around the time of Andrew and Fergie’s wedding.” By then, Robin avers, it became evident that High Tory Englishness was no protection against US capitalism.

Mention of ‘Invisible Touch’ can’t help but bring to mind Patrick Bateman in American Psycho. In perhaps the most hilarious scene in the movie, Bateman – US consumer-capitalism personified – perfectly ventriloquizes the Eighties’ revisionist take on Genesis’ career:

‘I’ve been a big Genesis fan ever since the release of their 1980 album, Duke. Before that, I really didn’t understand any of their work. Too artsy, too intellectual. It was on Duke where, uh, Phil Collins’ presence became more apparent. I think Invisible Touch was the group’s undisputed masterpiece. It’s an epic meditation on intangibility. At the same time, it deepens and enriches the meaning of the preceding three albums… Listen to the brilliant ensemble playing of Banks, Collins and Rutherford. You can practically hear every nuance of every instrument. … The peak of professionalism. … Take the lyrics to Land of Confusion. In this song, Phil Collins addresses the problems of abusive political authority. In Too Deep is the most moving pop song of the 1980s, about monogamy and commitment. The song is extremely uplifting. Their lyrics are as positive and affirmative as, uh, anything I’ve heard in rock. … Phil Collins’ solo career seems to be more commercial and therefore more satisfying, in a narrower way. Especially songs like In the Air Tonight and, uh, Against All Odds. … But I also think Phil Collins works best within the confines of the group, than as a solo artist, and I stress the word artist. This is Sussudio, a great, great song, a personal favorite.’

(But, like Gabriel’s ‘Melt’ album, [the one which includes ‘Games Without Frontiers’ etc.], wasn’t ‘In the Air Tonight’ Collins’ take on Neuwave?)

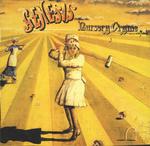

Certainly, what fascinates about the early Genesis is the quaint Olde Worlde Englishness of their record covers. Take the Nursery Cryme sleeve (see above), with its sinister Lewis Caroll croquet lawn and suggestion of a Faery-tale Albion of pantomime-gone-bad Punch and Judy menace. I’m not sure I’ve heard this one, to be honest, but the Gabriel-era Genesis I have heard falls disappointingly short of the English Can-plus-Spirit of Eden-plus Edward Lear plus medieval carnival perverse pastoral epic I idly imagined. Gabriel’s vision and voice – then that quasi-hysterical anglo-quaver – were the saving graces but really the band are so poor, so lacking in imagination and deftness, that the end result is not the nobly deluded, elephantine absurdity one always associates with Prog, but a plodding, workmanlike competence. Like most Prog I’ve heard, Genesis’ problem is not self-indulgent excess; it’s dullness. Listening to the two Gabriel Genesis tapes I have (borrowed long ago from my Prog correspondent, Bruce), what strikes me about their music is its lack of nuance. It is either Quiet or Loud – no middle ground, no eddying flow or ebbing undercurrents, just a stuttering study in jerky contrast. Isn’t that jabbing masculine jerkiness, that anti-plateau jumpiness, what is so much of a turn-off about Prog? Genesis’ sound was English by default – still Blues/ r and r-based, it was English only in the sense that it was a specifically English take on American forms, not in the sense that it evoked England.

What I’ve heard of Gabriel’s solo stuff is much more intriguingly English than Genesis. I’ve always found ‘Solsbury Hill’, for instance, movingly evocative of the rural English experience: the sharpness of clear air, that hollow, mossy feeling of earth beneath the feet, the town lights scattered below. In any case, if Gabriel-era Genesis were a failed attempt to produce a convincingly English rock sound, Collins-era Genesis and post-‘Sledgehammer’ Gabriel were an achieved attempt at simulating – and indeed outdoing – US AOR. Robin is right; by then, there is not a trace of English public school resistance to American hegemony. They are part of the programme.

But what is it that ‘Sledgehammer’ ends? I’ll come back to that.