RETURN THE TICKET

Mon. January 3, 2005Categories: Abstract Dynamics

(Apologies for interruption of service; due to serious problems with my flat, I have had to move all my stuff to Scanshift’s place for a while… Major upheaval obv so no time… (Ab)normal service should be resumed tonight when I set up my computer…. That which does not domesticate me, that which breaks my habit lines, makes me stronger….)

‘Man’s creations have been destroyed by Mother Nature…’ (ITN news Sunday evening) (Ah, so it’s a woman’s fault, as usual).

Astonishing, really astonishing piece in The Telegraph on Sunday by the Archbishop of Canterbury, in which he said that it understandable that the tsunami has made believers questions their faith in God.

Thousands of people dying each day from poverty, but that doesn’t make us question our faith. Six million exterminated in the Holocaust, but a merciful, lovng, personal God could stand by and watch that happen. And previous natural disasters that have destroyed whole populations, whole cultures. Pompeii, Lisbon, Krakatoa. Even children know of these catastrophes.

What is Williams saying? That it took television pictures to suddenly bring home to him the reality, the obvious reality, of the omnipresence of human suffering, the indifference of nature, the sublime cruelty of fate?

What faith is this, that has never confronted such matters?

Williams must be being disingenuous, surely. It is not as if the problem of suffering hasn’t been recognized by theists as the most intractable, most terrible dilemma to which belief in the personal God gives rise. I can only assume that he was playing to the gallery, cynically colluding with tabloid piety (which always goes alongside tabloid cynicism – the same old tawdry tits and tat, emotional and physical pornography, the sensational collaging of sex and catastrophe that made the then still openly moralistic McLuhan recoil in horror from newspaper front pages in The Mechanical Bride).

As Williams is well aware, the Christian response to evil and suffering has usually taken one of two forms: the Augustinian and the Irenaean theodicies.

Augustine’s brief was to ward off the Manichaean Heresy: the doctrine that the universe is primordially divided into a Good and Evil, which are in balance. Augustine used all his diabolic intelligence to resolve the prima facie irreconcilability of the belief that God created everything with the (apparently) undeniable reality of Evil. Yes, God created every Thing, Augustine insisted, but Evil is not a Thing, it is not a substance, it is a privative, a lack, a failure of the Good. The consequence of this was that, while Good was necessary in order that Evil might exist, the reverse was not the case. Since Evil is only a lack of Good, wherever there is Evil there must be Good. Augustine uses the analogy of blindness. Blindness, like all evils, could not exist in its own right; it was only a failure of sight.

Augustine supplemented this ontological account of Evil with an ‘Historical’ account derived from Genesis. Evil comes from Man (misled by Woman, natch) turning away from God. Both Moral AND Natural evil are consequences of this act of rebellion. No earthquakes or tsunamis in Eden.

Hence the doctrine of Original Sin; the formula ‘sin is either sin or the consequences of sin’ allowing Jahweh to attribute his negligence to other, human, Fathers.

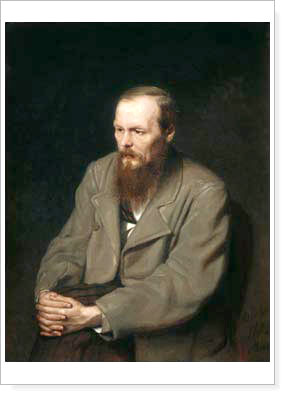

Yet this ‘justification’ was easily prey to the anguished protest Dostoyevsky’s Ivan Karamazov howled out:

‘If they [children], too, suffer horribly on earth, they must suffer for their fathers sins, they must be punished for their fathers, who have eaten the apple; but that reasoning is of the other world and is incomprehensible for the heart of man here on earth. The innocent must not suffer for anothers sins, and especially such innocents!’

So now, even the Roman Church of Child abuse has all but abandoned the cruel genius of Augustine, and turned to versions of Ireanaus’ theodicy.

Irenaeus’ adversaries were not the Manicheans, but the Gnostics (and indeed much of our knowledge of Gnostic writings and thoughts in fact comes from Irenaeus’s satires and attacks upon them). The Gnostics, like Hume and Schopenhauer after them, drew the obvious conclusion from the endemic suffering and misery of the world: if the planet was designed at all, they suggested, then it must have been the work of a demented sadist.

To combat this reasoning, Irenaeus argued that it was plain that the world could not have been designed as a place fitted for human happiness. It must then be what John Hick, following Keats, calls a ‘vale of soul-making’. Evil and suffering are challenges, opportunities for us to grow and develop as individuals. A world without suffering would be a meaningless cartoon in which no actions carried moral weight, since nothing anyone did would have any real consequences.

This rationalization of moral and natural evil does nothing, really, to address the basic ontological scandal which obtains as soon as there is one innocent who suffers. No divine plan, no post hoc rationalization of suffering could possibly make good the pointless agony of one child – and a God who conceived of such suffering as part of an overall divine plan would have to be a cruel and vicious monster.

‘Can you understand why a little creature, who cant even understand whats done to her, should beat her little aching heart with her tiny fist in the dark and the cold, and weep her meek unresentful tears to dear, kind God to protect her? Do you understand that, friend and brother, you pious and humble novice? Do you understand why this infamy must be and is permitted? Without it, I am told, man could not have existed on earth, for he could not have known good and evil. Why should he know that diabolical good and evil when it costs so much? Why, the whole world of knowledge is not worth that childs prayer to dear, kind God! I say nothing of the sufferings of grown-up people, they have eaten the apple, damn them, and the devil take them all! But these little ones! I am making you suffer, Alyosha, you are not yourself. Ill leave off if you like.

….

But what pulls me up here is that I cant accept that harmony. And while I am on earth, I make haste to take my own measures. You see, Alyosha, perhaps it really may happen that if I live to that moment, or rise again to see it, I, too, perhaps, may cry aloud with the rest, looking at the mother embracing the childs torturer, Thou art just, O Lord! but I dont want to cry aloud then. While there is still time, I hasten to protect myself, and so I renounce the higher harmony altogether. Its not worth the tears of that one tortured child who beat itself on the breast with its little fist and prayed in its stinking outhouse, with its unexpiated tears to dear, kind God! Its not worth it, because those tears are unatoned for. They must be atoned for, or there can be no harmony. But how? How are you going to atone for them? Is it possible? By their being avenged? But what do I care for avenging them? What do I care for a hell for oppressors? What good can hell do, since those children have already been tortured? And what becomes of harmony, if there is hell? I want to forgive. I want to embrace. I dont want more suffering. And if the sufferings of children go to swell the sum of sufferings which was necessary to pay for truth, then I protest that the truth is not worth such a price. I dont want the mother to embrace the oppressor who threw her son to the dogs! She dare not forgive him! Let her forgive him for herself, if she will, let her forgive the torturer for the immeasurable suffering of her mothers heart. But the sufferings of her tortured child she has no right to forgive; she dare not forgive the torturer, even if the child were to forgive him! And if that is so, if they dare not forgive, what becomes of harmony? Is there in the whole world a being who would have the right to forgive and could forgive? I dont want harmony. From love for humanity I dont want it. I would rather be left with the unavenged suffering. I would rather remain with my unavenged suffering and unsatisfied indignation, even if I were wrong. Besides, too high a price is asked for harmony; its beyond our means to pay so much to enter on it. And so I hasten to give back my entrance ticket, and if I am an honest man I am bound to give it back as soon as possible. And that I am doing. Its not God that I dont accept, Alyosha, only I most respectfully return him the ticket.’

Yes, suffering should make theists lose their infantile faith in the Big Daddy. Which is why the only concept of God that makes any sense, that offers any comfort, is the impersonal God, the God which is Nature, and which has no will, which does not punish, and has no interests or desires whatsoever.

A very thought provoking post, to be sure. The early Church’s attempts to deal with the various heterodoxies and heresies of gnosticism are things we should all be reminded of periodically, because to even remind people that the Church has a history of internal dissent is itself useful in getting people to see that there is a lot more to all of it than the crap they are fed in Sunday school.

However, Ill limit myself in this response to what I find interesting about Dr. R.W.’s little intervention. This may have the effect of coming off like a defence of Dr. Rowan, which is not really my intention. What Id like to do is contrast R.W.s musings with what I see as the really virulent and nasty aspect of Xianity.

To me, what’s interesting about his latest press conference/twitter is that it offers a way out of faith. One obvious response to such an outburst by the prelate might go something like this: Why the hell would anyone bother to bring up the fact that such disasters as the tsunami rightly cause Xians to doubt their faith, and then go right ahead and come to the wrong conclusion? That is, if you are going to point out to believers that the existence of evil and suffering in the world should cause those of us with even a smattering of common sense to doubt the existence of a merciful and benevolent God, but then go on to recommend the conclusion that nevertheless there is a benevolent and merciful god, then this just sounds fucking crazy, or at the very least highly disingenuous. But I don’t want to stop with this analysis.

I think it is quite unusual for a leader of a “major religion” (if you can really call the C of E that) to bring up these kinds of questions, even if said leaders simply try to foist a stupid conclusion on their listeners. Because to bring up the matter of faith in the context of rational argument is a hell of a lot better than the usual tack, which is to couch matters of faith in terms of fire and brimstone.

Perhaps this is because I am living in the US, but no church leader here would even attempt such an argument in a press intervention. Religion, and particularly Xianity, is understood here to be a matter of fear, not rational discussion. In this approach to religion, Faith is a matter of obeying the putative commands and supposed history presented in the Bible, not of trying to make religion or personal faith fit in with how the world actually is. Rather, it is the world which must be twisted, bent, and jammed into the framework of revealed religion, so as not to upset the Big Guy up there, who will surely damn anyone who questions their faith to eternal firey stuff. That is, people believe because they are afraid that something bad will happen to them if they dont. And when bad things happen to believers, it is because they didnt believe well enough.

What I like about Rowan then, is that to bring up this tired theodicy is still much better than to not bring it up. For what he is doing, in effect, is framing such matters of faith in the context of rational thought, which is not nearly so noxious as to frame faith in the context of fear. It seems to me that the only other response Xianity has to a disaster of the magnitude of the tsunami is to note that good Xians have a duty to help the survivors, and to leave it at that. However, what seems to be implicit in this kind of response, to my mind, is that when bad things happen to people, they must have somehow deserved it. And we, as the survivors, have a Xian duty to try to help out those poor souls. There but for the grace of God etc etc. shit. Since the fear approach as I am outlining it here says that you had better obey god, or something bad will happen to you, blaming the victim seems like the only possible response to evil. And this is what is truly disgusting about Xianity in my opinion.

Getting back to the good Dr. R. W., I’m going to give him kudos for presenting the theodicy at all, since it leaves a person with half a brain the possibility of simply rejecting R.W.’s conclusion. If you can say to people “look, this really bad thing is the kind of thing that makes people doubt their faith” this allows people to…actually doubt their faith! And that to me is a good thing. The other option of Xianity is simply to blame the victim.

I think we can even see a bit of this in Irenaeus’ attempt to deal with the problem of evil. Augustine simply denies evil exists, whereas Irenaeus tells us that evil is a test or challenge for us, and that we have to take evil as an opportunity to grow (incidentally Richard Swinburne has also lately used this tack (I think in Providence and the Problem of Evil 1998), and presents a nice little story about a woman imprisoned in Chile in the 1970s who was repeatedly beaten and raped with a cattle prod. His conclusion? That if this hadn’t been done to her, she would never have experienced what true faith was….ugh!)

The idea that evil is a test, I think, is very close indeed to simply blaming people when bad things happen to them. This theodicy is more disgusting to me, because it is more effective in terms of being a mind virus. If you can get people to believe in God through fear, then you almost have to tell them that when bad things happen, it is the fault of the victim. And people have no choice but to accept this. R.W.’s pathetic discussion seems rather encouraging to me in contrast, because he is unknowingly facing up to the end of the C of E. If the C of E is even presenting to its adherents the option of doubting one’s faith, it’s in a sorry state indeed. And I for one enjoy watching the fag end of a religion, played out in glorious technicolour.