Ontological rot

Wed. November 15, 2006Categories: Abstract Dynamics

I present below a piece on Nigel Cooke which was originally intended to be published in the Portuguese magazine, Slang; sadly the magazine has folded, so waste not, want not… I think I compared Cooke to Burial in the first post I wrote on the album…

.jpg) | .jpg) |

The theme of Nigel Cooke’s paintings, a small number of which were exhibited in his show ‘A Portrait of Everything’ at the South London Gallery earlier this year, might best be described as ontological rot.

Cooke’s work explicitly presents us with what seem to be (at least) two different realities, both decaying. His foregrounds, typically, are ultra-naturalistic (christmas card snow scenes are a particular favourite). The backgrounds, meanwhile, are desolated, empty to the point of being Tanguy-abstract. Typically, they are also defaced by graffiti.

Why is Cooke so fascinated with graffiti? He has described the rendering of graffiti in his painting he uses oil paints to create the effect as ‘slowed down street language’, and there is a way in which his paintings function like a motion capturing device, transliterating the energies of urban culture into paint. This is painting after hip hop and jungle, with the paintings’ ‘impossible architectures’ paralleling the bizarre topologies invented by sampler-based sonic productions.

.jpg)

Richard Dadd, The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke (1855-1864)

The graffiti in Cooke’s paintings seems to do two things at once: it does ontological violence to the represented reality of the paintings by drawing our attention to the fact that, after all, the painting is nothing more than a flat surface – it tells us what we already know: this is not a world. At the same time, the graffiti constitutes itself as a reality, a painting within a painting (or perhaps a painting over a painting): this is a world, it insists. And, immediately, we have to infer the existence of yet another reality, this time unseen – the reality of the graffiti-painter, the ‘idiot’ author who has defaced the represented world of the painting. Here we are in the painting equivalent of the textual labyrinths designed by Beckett, Borges or Robbe-Grillet, but instead of embedded authors, we have an embedded painter, a creature-turned-creator, a golem-become-god, a drunken demiurge who must conjure a world with only a spraycan to hand.

Nigel Cooke, The Philosopher (2005)

What kind of world does Cooke’s wounded god dream up? It is a world let us call it late capitalism of the rejected, the dejected and the addicted. When he spoke at the Tate a few months ago about the relationship between his work and the Gothic, Cooke described his anthropomorphic flowers and vegetables as figures from advertising or children’s stories who have grown up and found themselves in dead-end jobs.

.jpg)

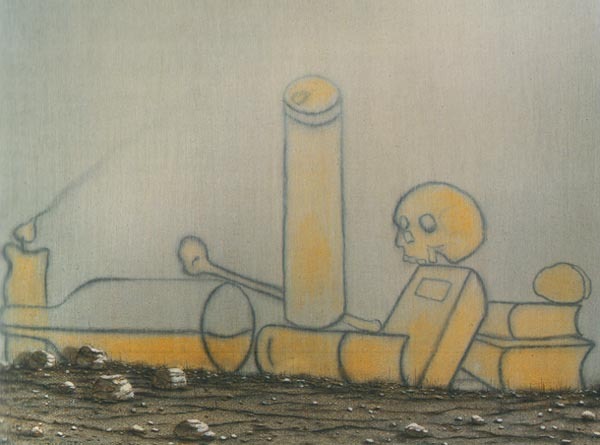

Nigel Cooke, Thinking (2005)

The graffitied figures on/in the paintings – the junkie vegetables, the smoking flowers, the morose, hungry bones – can be related, not only to their sprightlier cousins in advertising, but to their ancestors in fairy paintings. What have fairy myths been about, after all, if not a world hidden within our world? The fairy world vivid, hyperdetailed – was a delirial aristocracy, often cruel and exploitative, dreamt up by minds intoxicated with psilocybin. The drug analogue for Cooke’s fairy gardens gone to seed would not be a fungus consumed on some greed glade but housing estate heroin. The flowerbeds have become a junkyard. They are not teeming with a fecund, indominitable Life, but populated by creatures who have taken one step towards animation, then fallen back into the mineral condition of addiction. The paintings are illustrations for fairy tales re-written by the Freud of Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

Nigel Cooke, Beer and Wine (2005)

A timeless image of Death lies miserable in front of us. A pathetic cowled bone. It could be a medieval plague victim or a kid in a hooded top stalking a shopping mall.

Graffiti painters, Baudrillard enthused in 1977, free walls ‘from architecture and turn them again into living, social matter.’ In Cooke’s paintings, by contrast, graffiti turns living, organic landscapes into walls. The rural-vital becomes the urban-undead. Cooke described his paintings as a ‘flawed idea of representing the after-life’, saying that they were ‘a frontier site where paintings go to die, an elephant’s graveyard of images.’

Nigel Cooke, The Dead (2005)

It seems that all the worlds are rotting at once. The colours are fading. Everything looks washed out. Morning has broken, and there is no-one to fix it.

Thanks to Karl Kraft for the scans, and for introducing me to Cooke