Nomadalgia: The Junior Boys’ modernist MOR

Sat. March 4, 2006Categories: Abstract Dynamics

I’ve lived with the new Junior Boys’ album So This is Goodbye for nearly two weeks now… Or rather, it has lived with me and taken me over – its melodies taking up residence in the back of my mind, its moods interleaving with my own – a benign narcotic that grows more sweetly addictive with each listen. There’s no question it’s a masterpiece, but I suppose you knew I’d say that.

So This is Goodbye is to be released on Domino, also home of the Arctic Monkeys, and it’s an absurd irony that many casual listeners would cast the Junior Boys, not the AMs, as retro. That’s because rock has been eternalized, removed from any responsibility to renew itself, whereas electronic pop is cursed to be forever associated with a brief period in the 70s and 80s. But the synthpop revivalist tag has always been misleading and reductive in the case of the Junior Boys. Some of the Junior Boys’ textures may be borrowed from synthpop but, formally, their songs would be impossible without twenty years of the rave discontinuum. And where synthpop was self-consciously European, the Junior Boys have pioneered an electronic Pop that speaks in a Canadian accent. So This is Goodbye is a deeply Canadian record: crisp and white, like the Canadian winter.

Synthpop remained attached, for the most part, to the three-minute format; ‘extended’ remixes were a concession to the imperatives of Dance. But space comes as standard with the Junior Boys. Only one of So This is Goodbye‘s 10 tracks is under four minutes. Space is integral , not only to their sound, but to their songs. Space is a compositional component, a presupposition of the songs, not something retrospectively inserted at a producer’s whim. The pauses, the imagist-allusiveness of the lyrics, the breathy phrasing would not work, or make much sense, outside a plateau-architecture imported from Dance; crushed into three minutes Junior Boys’ songs would lose more than length.

|  |

The point can be reinforced by comparing So This is Goodbye to another recent electronic pop LP, Goldfrapp’s Supernature. Supernature‘s conceit is beautifully simple: imagine an alternative history of pop in which glam rock was played on synthesizers. The Alvin Stardust with moogs thing is often winning, but the form of the Goldfrapp Song remains pre-House, whereas House provides the template for much of So This is Goodbye‘s version of Pop. House references are everywhere: the title track is gorgeously, oneirically poised on a honeyed Mr Fingers’ plateau, and it is not only the arpeggiated synth which drives many of the tracks that is reminiscent of Jamie Principle. Yet the LP does not sound either like House or like most previous attempts to synthesize Pop with House. So This is Goodbye is like House if it had started in the wilds of Canada rather the clubs of Chicago. Too many House-Pop hybrids fill up House’s Space with business, hectic activity. On Vocalcity and, to some extent The Present Lover, Luomo did the opposite: dilating the Song into an unfolding driftwork. But the Luomo LPs were more Pop House than Pop per se. So This is Goodbye is, however, very definitely a Pop record; if anything, it’s even more seductively catchy than Last Exit.

The obvious difference between So This is Goodbye and its predecessor is the absence of the tricksy stop-start stutter beats on the new record. (That aspect of the Junior Boys will be explored and extrapolated by former JB Jonny Dark, whose record is soon to be released by the JBs’ old label, kin.) If Junior Boys’ inventiveness is no longer concentrated on beats, that is a reflection as much of a decline of the surrounding Pop context as it a sign of the JB’s newfound taste for rhythmic classicism. Last Exit‘s reworkings of Timbaland/Dem 2 tic-beats meant that it had a relationship with a rhythmic psychedelia that was, then, still mutating Pop into new shapes. In the intervening period, of course, both hip hop and British garage have taken a turn for the brutalist, and Pop has consequently been deprived of any modernizing force. Timbaland’s beat surrealism became water-treading repetition years ago, displaced by the ultra-realist Thuggish plod of corporate hip hop and the ugly carnality of Crunk; and 2 Step’s ‘feminine pressure’ has long since been crushed by the testosterone-saturated bluntness of Grime and Dubstep. That skunk-fugged heaviness remains the antipodes of the Junior Boys’ cyberian, etherealized, plaintive physicality; listening to the Junior Boys after Grime or Dubstep is like walking out of a locker room thick with dope smoke out onto a Caspar David Friedrich mountain. A lung-cleansing experience. (Significant also that those other ultra-heterosexual post Garage musics should have bred out the influence of House, while the Junior Boys return to it so emphatically.)

But the removal of rhythmic tricksiness perhaps also indicates something of the scale of the Junior Boys’ Pop ambitions, which are best seen as the pionering of a New MOR rather than another attempt at New Pop. If, as Simon convincingly proposes on this Dissensus thread , there is no cutting edge, then it makes more sense to abandon the former margins and refurbish the middle of the road. The Junior Boys’ songs have always had more in common with a certain type of modernist MOR – Hall and Oates, Prefab Sprout, Blue Nile, Lindsay Buckingham – than with any rock. Modernist MOR is the opposite of the discredited strategy of entryism: it doesn’t ‘conform to deform’, it locates the alien right in the heart of the familiar. The problem with current Pop is not the predominance of MOR, but the fact that MOR has been corrupted by the wheedling whine of Indie authenticity. In any just world, the Junior Boys, not the drippy moroseness of James Blunt nor the earthy earnestness of KT Tunstall, would be the globally dominant MOR brand in 2006.

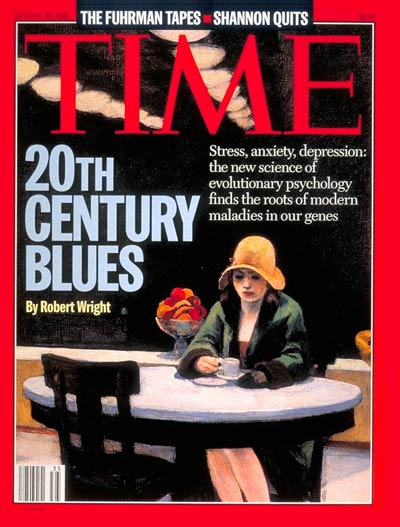

Ultimately, though, So This is Goodbye sounds more middle of the tundra than middle of the road. It’s as if the Junior Boys’ journey into North America Endless has continued beyond the late-night freeways of Last Exit. It’s like the first LP’s city lights and Edward Hopper coffee bars have receded, and we’re taken out, beyond even the small towns, into the depopulated wildernesses of Canada’s Northern Territories. Or rather, it’s as if those wildernesses have crept into the very marrow of the record. In The Idea of North, Glenn Gould suggests that the North’s icy desolation has a special pull on the Canadian imagination. You hear this on So This is Goodbye not in any positive content so much as in the Song’s gaps and absences; the gaps and absences that make the Songs what they are.

Those crevices and grottoes seem to multiply as the album progresses. The second half of the album (what I hear as the ‘second side’; one of the most gratifying things about So This is Goodbye is that it is structured like a classic Pop album, not an extras-clogged CD) diffuses forward motion into trails of electro-cumulae. The title track sets stately synths against the anti-climactic urgency of Acid House’s Forever Now: the effect like running up a down escalator, frozen in an aching moment of transition. ‘Like a child’ and ‘Caught in a Wave’ immerse the agitated drive of the LP’s signature arpeggiated synth in a vapour trail of opiated atmospherics.

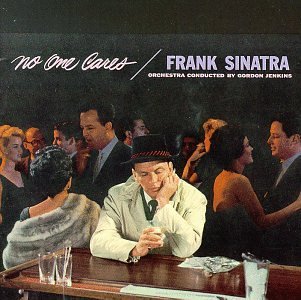

The reading of Sinatra’s ‘When No-one Cares’ is the knot which holds together all of So This is Goodbye, a clue to its modernist MOR intentions (lines from the song – ‘count souvenirs’, ‘like a child’ – provide the titles for other tracks, almost as if the song is a puzzle the whole album is trying to solve). So This is Goodbye‘s songs bear much the same relation to high-energy as the late Sinatra’s bore to big band jazz: what was once a communal, dance-oriented music has been hollowed out into a cavernous, contemplative space for the most solitary of musings. On the Junior Boys’ ‘When No-one Cares’ beats are abandoned altogether, the track’s ‘endless night’ lit only by the dying-star flares and stalactite-by-flashlight pulse of reverbed electronics.

The Junior Boys have transformed the song from the lonely-crowd melancholy of the original – Frank at the bar staring into his whisky sour, happy couples partying obliviously behind him (or in his imagination) – into a lament whispered in the wilderness, icy-breathed into the black mirror indifference of a Great Lake at midnight. It is as cosmically desolated as the Young Gods’ version of ‘September Song’, as arctic-white as Miles Davis’ Aura. ‘When No-one Cares’ is one of my favourite Sinatra songs, and I must have first heard it twenty years ago, but with the Junior Boys’ version – which makes the catatonic stasis of the original’s grief seem positively busy – it is as if I am hearing the words for the first time.

Sinatra’s No-One Cares (which could have been subtitled: From penthouse to Satis House) was like Pop’s take on literary modernism, an affect (rather than a concept) album, a series of takes on a particular theme – disconnection from a hyper-connected world – with Frank the ageing sophisticate adrift in the McLuhan wasteland of the late 50s, Elvis already here, the Beatles on the way (who is the ‘no-one’ who doesn’t care if not the teen audience who have found new objects of adoration?), the telephone and the television offering only new ways to be lonely. So This is Goodbye is like a globalized update of No-One Cares, its images of ‘hotel lobbies’, ‘shopping malls we’ll never see again’ and ‘homes for sale’ sketching a world in a state of permanent impermance (should we say precarity?). The songs are overwhelmingly preoccupied with leave-taking and change, fixated on doing things for the first or the last time. ‘So This is Goodbye’ is not the title track for nothing.

Sinatra’s melancholy was the melancholy of mass (old) media technology – the ‘extimacy’ of the records facilitated by the phonograph and the microphone, and expressing a peculiarly cosmopolitan and urban sadness. ‘I’ve flown around the world in plane/ designed the latest IBM brain/ but lately I’m so downhearted’, Sinatra song on No-One Cares‘ ‘I Can’t Get Started’. Jetsetting is now not the privilege of the elite so much as a veritiginous mundanity for a permanently dispossessed global workforce. Every town has become the ‘tourist town’ alluded to in So This is Goodbye‘s final track, ‘FM’, because now at home everyone is a tourist, both in the sense of permanently on the move but also in the sense of having the world at their fingertips, via the net. If Sinatra’s best records, like Hopper’s paintings, were about the way in which the urban experience produces new forms of isolation (and also: that such mass mediated private moments are the only mode of affective connection in a fragmented world), then So this is Goodbye is a response to the cyberspatial commonplace that, with the net, even the most remote spot can be connected up (and also: that such connection often amounts to a communion of lonely souls). Hence the impression that, if Sinatra’s ‘When No-one Cars’ was an unanswered call from the heartless heart of the Big Apple, then the Junior Boys’ version has been phoned-in down a digital line from the edge of Lake Ontario. (Is it accidental that the term ‘cyberspace’ was invented by a Canadian?)

So this is Goodbye is a very travel sick record. It expresses what we might call nomadalgia. Nomadalgia, the sickness of travel, would be a complement to, not the opposite of, the sickness for home, nostalgia. (And what of the relation between nomadalgia and hauntology?) It’s entirely fitting that the final track, ‘FM’, should invoke both ‘a return home’ and radio (not the only reference to that ghost-medium on the LP), since internet radio – with local stations available from any hotel in the world – is perhaps more than anything else the objective correlative of our current condition. A condition in which, as Zizek so aptly puts it, ‘global harmony and solipsism strangely coincide. That is to say, does not our immersion in cyberspace go hand in hand with our reduction to a Leibnizian monad which, although ‘without windows’ that would directly open up to external reality, mirrors in itself the entire universe? Are we not more and more monads, interacting alone with the PC screen, encountering only the virtual simulacra, and yet immersed more than ever in the global network, synchronously communicating with the entire globe?’