‘My death is everywhere, my death dreams’

Fri. March 9, 2007Categories: Abstract Dynamics

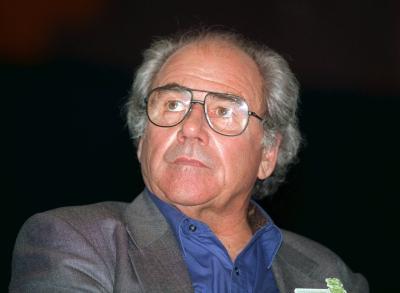

Baudrillard’s contribution can be most easily appreciated when you consider who condemned him and why. He was denounced by Brit-American empiricists as an incomprehensible obscurantist at the same time as he was dismissed by the overlords of Continental Philosophy for being a pop philosopher, flimsy and insubstantial. Behind these denunciations, you gain a glimpse of a theorist who was playful yet solemn, an opaquely lucid stylist who was in love with jargon and in touch with media.

Baudrillard was never quite laborious or detached enough to qualify as a Continentalist, nor even as a philosopher (he was based, improbably, in a Sociology department). Always an outsider, projected out of the peasantry into the elite academic class, he ensured his marginalization with the marvellously provocative Forget Foucault, which wittily targeted Deleuze and Guattari’s micropolitics as much as it insouciantly announced the redundancy of Focault’s vast edifice.

In Baudrillard, theory escaped the 60s. Baudrillard’s texts, in their disappointed tone as much as anything else, belong to our world, our era. The various revolutions of the sixties were petering out as Baudrillard began to produce his work. The system proved to be voracious, protean; it absorbed the attacks of its would-be enemies and sold them back as advertising. Critique was useless; new – fatal – strategies needed to be developed, which involved the theorist homeopathically introjecting elements of the system, the code, in the hope of setting the system against itself, overbalancing it.

It is a commonplace that science fiction reveals more about the time it was written than it tells us about the future. But Baudrillard’s self-styled science-fiction-theory – which drew upon the theoretical fictions of Ballard and Dick – actually did foretell the future, which is our present. Already, in the 1970s, Baudrillard was basing theoretical riffs on reality TV and the media logic of terrorism. His texts, which dispensed with the academic machinery of footnotes and references around the time of Symbolic Exchange and Death in 1977, became increasingly incantatory and aberrantly lyrical until they resembled a glacial cybernetic poetry, which, especially in the later works, you could easily believe was the work of some dejected AI, endlessly remixing its own concepts and linguistic formulas.

Baudrillard is condemned, sometimes lionised, as the melancholic observer of a departed reality. He was certainly melancholic, but what he mourned was not a lost reality but what he variously termed the illusory, symbolic exchange, the seductive. Reality disappeared at the same moment that art and artifice were eliminated. Deprived of its heightened reflection, extension and hyperbolization in myth, art and ritual, reality cannot sustain itself. It is the very quest to access reality in itself, without illusion, that generates the hyperreal implosion. Here, as Baudrillard long ago realised, reality TV is exemplary. Film an unscripted scene and you might not have art, but you do not have reality either. You have reality’s uncanny double, its excrescence: simulation, precisely.

Baudrillard: the prophet in our desert, the prophet of our desert.

‘The irreversibility of biological death, its objective fact and character, is a modern fact of science. Every other culture says that death begins before death, and that life continues after life, and that it is impossible to distinguish life from death. Against the representation which sees in one the term of the other, we must see try to see the indeterminacy of life and death, and the impossibility of their autonomy in the symbolic order.’

– Symbolic Exchange and Death

See also: Antigram and Sit down man…