Mors Ontologica

Thu. September 21, 2006Categories: Abstract Dynamics

- Spray a bug with a toxin and it dies; spray a man, spray his brain, and he becomes an insect that clacks and vibrates about in a closed circle forever. A reflex machine, like an ant. Repeating his last instruction.

In his recent interview with Ballardian, Iain Sinclair told Tim Chapman that theyre treating these literary classics from another era as if they were heritage Dickens. Probably thats a mistake youve got to really get down and hack it to pieces and find something that really works in film terms, something that honours the spirit of the original book. You cant just make the film of the book it doesnt work.

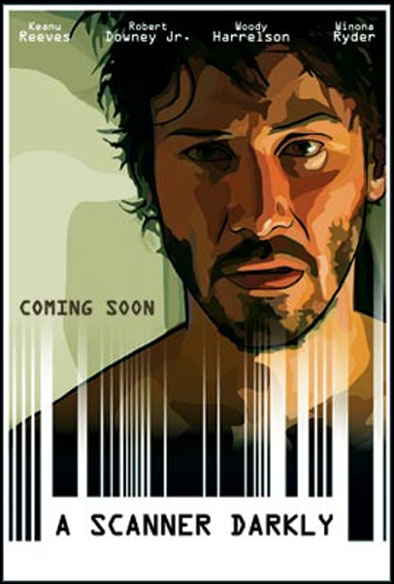

It would be hard to think of a film that follows this advice less assiduously than Richard Linklaters A Scanner Darkly, surely the most faithful adaptation of a PKD novel to date. Oddly, the rotoscoping technique adds to the sense of fidelity to the novel, since it has the effect of lending the film something of the oneiric vagueness of the images that pass through your mind as you read the book.

As Steven Shaviro pointed out, ‘the look and feel of the rotoscope technique is itself the real meaning’ of Linklaters A Scanner Darkly. ‘Rotoscoping, at least in Linklaters use of it, is rooted in the real, but the real has been somehow displaced or distorted with the implication that this displacement and distortion is itself, in a deeper sense, the bedrock Real of the society of addiction and control.’

I (contra Sinclair) maintain that, as a rule, SF adaptations should be made as period pieces, and Linklaters film works because it remains rooted in the 70s. There is no facile attempt to update the novel or its concerns. One of my problems with Weisss Atrocity Exhibition, the film which prompted Sinclairs remarks, is that it is not sufficiently rooted in the Sixties.

A Scanner Darkly is about the painfully drawn-out end of the Sixties the collapse of psychedelic expansiveness into sulphate pyschosis. Its analogue in pop would lie somewhere between the sleazy strung-out street corner clamour of On the Corner and the burned-out synaptic tenements of Unknown Pleasures, between Funkadelic’s derangement at its most doleful and Cabaret Voltaire’s paranoia at its most personality-disintegrated. A Scanner Darkly is one of Dicks bleakest novels, and almost certainly his saddest. Few could remain unmoved when confronted with the list of real-life casualties listed at the end of the novel (a litany of the drug-damaged that Linklater solemnly repeats at the end of the film).

- To Jim … deceased

- To Val … massive permanent brain damage

- To Nancy … permanent psychosis

- … and so forth

Although it was published in 1977, A Scanner Darklys mood is already postpunk. Or postpostpunk, since the novels scenario speedfreaks inserted into an acephalic Control apparatus fast forwards past the highs and cuts straight to the comedown whine of long-term psychiatric damage, institutionalisation and premature death. Both the novel and the film are remarkable, in fact, for their unstinting desublimation of drugs . The most censorious anti-drug campaigner could not have portrayed them more negatively. Only the bad side of Substance D (=speed) permanent psychosis, bugs crawling from out under the skin into the Real, where they are ineradicable is expressionistically presented. Instead of showing the speed rush from inside the delirium, Dick and Linklaters unblinking scanners (as unforgiving as a reality TV camera) record the vices of the habitual drug-user – unreliability, tedious self-involvement, a seemingly infinite capacity to squander time and resources – from outside.

- ‘The dead… who can still see, even if they can’t understand: they are our camera…’

Both the novel and the film function as a kind of requiem for speed. In the immediate postwar years, amphetamine was sold – like ubik – as a wonder-drug cure-all prescribed for a stupefyingly compendious array of medical problems, including asthma, epilepsy, obesity, travel sickness, narcolepsy, schizophrenia, impotence, Parkinsons disease, hyperactive disorders in children and apathy in old age. A 1946 report listed thirty-nine different disorders for which Benzendrine only one of the three main types of amphetamine was the recommended treatment.

- In the USA in the 1940s, there was little need for an illicit market in speed. Legally manufactured pharmaceutical tablets could be bought wholesale over the counter by any adult at a price of about fourteen pills per penny a staggering 75 cents per thousand speed pills. It would not be hyperbole to say that speed was being sold like sweets are sold to kids. Tablets continued to be available over the counter without prescription until 1951. During the 1950s and 1960s, amphetamines were being widely prescribed for fatigue, as slimming aids and even marketed in combination with barbiturates as Drinamyl (purple hearts) for depression. In 1958, 3.5 billion tablets were produced in the USA alone enough to supply every man, woman and child in the country with twenty standard doses. (Miriam Jospeh, Speed)

Amphetamine, safe if used as directed? Even the advertising slogans Joseph cites such as Two pills are better than a months vacation sound like they have been lifted wholesale from Dicks fiction.

There is a sense in which – metonymically – speed was postwar, prepostmodern capital, not only because amphetamine gave users more time to consume, but because it induced their bodies into a becoming-capital. As they ingested speed, users transformed their own nervous systems into miniaturized version of capitals boom and bust cycles. Like capital, speed, in itself, is nothing; the great pretender, a charlatan that deceives the body into adjusting to heady heights of nervous activity by

altering its internal thermostat, speed stimulates, but without bringing any new energy into the organism. Like speed, capitals hype-dynamics appear to produce something from nothing. But the cost when it is called in – and it always is – is vast …

Speed was certainly the Cold War drug – everyone knows that Kennedy was famously wired during the Cuban Missile Crisis – and seeing A Scanner Darkly now makes one suddenly aware that Dicks fiction presupposed the Cold War as a constant backdrop. The Cold War recurs – distorted, refracted, deflected -as a Real in all of Dick’s worlds. It’s possible to position A Scanner Darkly was one of the last moments in a trajectory of Cold War SF paranoia dating back to the 50s. SF and the Cold War were inseperable from the start: it would be too hasty to say that something like Invasion of the Body Snatchers was a simple transposition of Cold War paranoia into SF, because the Cold War itself already mobilized a Science Fictional language of stealth invasion, parasitism and insidious transformation.

Its no surprise, then, to find that A Scanner Darkly is the novel in which Dick is closest to Le Carre. The phrase Zizek uses to describe Highsmith’s deadlocks and longueurs – the inertia of the Real – applies equally to Le Carre and Dick. In all three, narrative runs aground on ‘the lack of resolution, the dragging-on of the “empty time,” which characterize the stupid factuality of life.’

- Waiting, and listening.

- Waiting, and listening, and remembering.

- Waiting, and listening, and remembering – more or less baldly ad hoc, or only the tiniest bit better than the Other Side’s other chap. (Waiting for the doppleganger Man.) Waiting, and listening, and drinking, and trying to manoeuvre other people into your version of a future, which is never really any kind of future proper, because futures are entirely unpredictable (which is also why they are hated by conspiracy nuts.), whereas yours is more like future memory in waiting you have tailored to fit whoever you’re currently talking to. (Ian Penman on Le Carre)

Inertia… Although Dick already takes for granted what Donna Haraway will eventually plod onscreen to tell us: that we are disturbingly inert, while our machines are disturbingly lively. When Dick recounts the same message, it is in the terms of Beyond the Pleasure Principle: ‘The drive of unliving things is stronger than the drive of living things‘

In A Scanner Darkly, as in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, all intersubjective relations devolve into webs of suspicion and betrayal. It goes with the territory, and the territory is nowhere – an existential East Berlin where everything you do has to be deniable. You’re guided by the grim categorical imperative which agents ignore at their peril: act as if the person to whom you are talking to will sell you out. If they haven’t fucked you over yet, just wait… If they don’t fuck you over, you’ll do it to yourself… Before long, you split in two, like Arctor, and then there’s no way back (all the king’s horses and all the king’s men … ). But total mental breakdown is the best cover of all (‘they can’t interrogate something, someone, who doesn’t have a mind’). Double agents, double lives, shivering on street corners, not sure if you’re the Man or waiting for the Man, but you’re always waiting… Cold war and junkie Cold, cold efficiency (“I am warm on the outside, what people see. Warm eyes, warm face, warm fucking fake smile, but inside I am cold all the time, and full of lies”), the duplicities and self-deceptions of the addict doubling those of the spy in deep cover:

- I get the idea Donna is a mercenary, he thought. … And they are the most wraithlike. They disappear forever. New names, new locations. You ask yourself, where is she now? And the answer is –

- Nowhere. Because she was never there in the first place.

Wraiths, spooks, ‘evaporating girls’, stalking a morally neutral Greeneland in which everyone plays a part but no-one is responsible. Here, paranoia no longer assumes the florid form of Schreber’s delirium; it is routinized, as grey as used bed sheets, as solid as styrofoam, a ‘monochrome game of disappointment, deferral, the next drink, the clink of ice cubes, the creak of mattress springs, the abyssal swirl of cigarette smoke up to the ancient ceiling….’ (IP again)

- There is little future … for someone who is dead. There is, usually, only the past. And for Arctor-Fred-Bruce there is not even the past; there is only this.

The novel is actually set in 1992, and it ominously foreshadows the permanent winter of postmodernity. ‘The winter of spirit. Mors ontologica. When the spirit is dead.’ Arctor-Fred-Bruce’s passage from speedfreak schizophrenic to patched-up penitent uncannily anticipates the switch from speed-modernism to depression that the culture as a whole will undergo. ‘No future … only this‘. Dick’s coolly precise diagnosis of the former Arctor’s condition applies to postmodernity in general:

- “That’s what it means to die, to not be able to stop looking at whatever’s in front of you. … You can only accept what’s put there as it is.”

- “How’d you like to gaze at a beer can throughout eternity? Might not be so bad. There’d be nothing to fear.”

- “He will never again in his life, as long as he lives, have any ideas. Only reflexes.”

Postmodernity as undeath… Reiteration without the possibility of innovation… you’re dead, but you don’t know it…. Human time has run out…

- … no time any more for Bob Arctor. His time – at least if measured in human standards – has run out. It was another kind of time which he had entered now. Like, she thought, the time that a rat has: to run back and forth, to be futile. To move without planning, back and forth, back and forth.

The New-Path centre where Arctor-Fred-Bruce is sent to ‘recover’, with its the mixture of Gestalt nonsense, tranquilizer-enforced pacification and cheap religiose piety, is almost an archetype of postmodern power. Nothing new in New-Path…. No future…only this. The section of the novel in which PKD describes the induction into New-Path – the dead-eyed Arctor-shell asked to mop the floor by an orderly, then sitting impassively, indifferently, a thousand miles away, while others converse ghoulishly around him – chillingly captures the blank withdrawal of clinical depression and the banal horror of institutionalization. No future… only this.

In the (circa 1945-1989) speed modernist era, culture, technology and social change were in a relationship of interexcitation. Postmodernity, by contrast, is characterized by a radical disjunction between technological and social change on the one hand and culture on the other. The rate of technological and social change has by no means decreased quite to the contrary in fact but culture no longer acts as a transmitter and intensifier but as a future-shock absorber (Eshun), which cools and slows the impact of the new. Culture increasingly falls into the role of retrofitting the anomalous into the homely. The Graphic User Interface of the PC – which familiarizes the front-end of the computer by converting it into something that can be understood through the rear-view mirror – is a perfect illustration of this trend. Gadgets themselves take on the role that speed once played – consider the endless electric midday that computer games open up, for instance – with Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) now acting as the dampeners in a seamless stimulus-control interpacification circuit. Look into the black-rimmed insomniac eyes of a teenager to see the system at work… SSRIs are the neurological band-aid late-capital puts on the brain damage it inflicts…

SSRIs are the perfect therapeutic drug for Control society, since they don’t so much cure depression as manage and normalize it. The ‘side-effects’ of SSRIs include slowness of thought, reduced libido and suicidal impulses, i.e. depression. But, since SSRIs suffuse you in a cotton wool haze, you no longer care that you are depressed. You feel like Fred in New-Path, well-adjusted to the fact that nothing can ever happen again. (Why did you ever think it could?)

It’s worth noting here that the widespread use of mood-altering drugs for depression and anxiety points to an inconsistency in commonsense metaphysics. Most people find the idea that the mind is the brain abhorrent, yet they happily take drugs whose efficacy presupposes just such an equivalence. (Dick’s 1964 novel, The Simulacra, begins with the banning of psychoanalysis: the only permissible treatment for mental illness is pharmacological.)

Perhaps more than any other writer, Dick anticipated the way that postmodernity would turn out, so it is both ironic and fitting that Dick’s own fictions should have been so central to postmodern culture. There has been no film more important in postmodernity than Blade Runner, and it is to be hoped that Linklater’s A Scanner Darkly might rescue Dick (and also SF) from the by now almost entirely negative influence of Ridley Scott’s film.

Gibsons novels are not fashionable at the moment, but despite Neuromancer being so similar to Blade Runner that when he first saw the film, Gibson thought that he was dreaming it, that that the images were streaming direct from his unconscious – Blade Runner remains canonical. Yet Blade Runner, like Neuromancer, effectively postmodernizes both pulp and the avant garde. Noir – itself postmodernized – is the vehicle for this appropriation, providing the texts with a ready-made (and by now far too familiar) veneer of stylishness and street sass. Gibson referred to his use of Burroughs, Ballard and Dick as an airbrushing. This description would apply equally well to Scotts hyper-aestheticized rendition of Dick, which excises all the trash which isn’t picturesque, elmininates the low-rent kookiness and transforms Dick’s balding, paunchy losers into classically anti-heroic Noir ‘tecs. Blade Runner‘s impact quickly went beyond influence, and it became metonymically implicated in late capitalism. Scott’s Noir near-future quickly collapsed into capital’s postmodern present; at a certain point in the eighties, it seemed that every advert was filmed inside the Tyrell corporation. Hollywood, evidently, was hypnotized by Blade Runner; and after The Matrix, SF remains trapped in the sleek, chic noir-lite black leather prison that Blade Runner designed.

Of all the substractions that Scott makes, the most significant is the excision of the theme of ontological vertigo, or reality bleed, from Dick’s fiction. (In maintaining a focus on that theme, Verhoevens pulpier Total Recall is far closer to PKD than is Blade Runner). The question around which Blade Runner is organized is this an android or is it a human? effectively keeps it locked at the level of Baudrillards second order of simulacra, but the prescience of Dicks fiction was to have broached the third order of simulacra, where the status of reality as such is in question. Dicks affinity with Gnosticism consists in large part in his suspicion that the whole of lived reality, not merely technical artefacts within that frame, is a simulation.

In A Scanner Darkly, the moment of reality bleed comes when, in the words of Steve Shaviro,

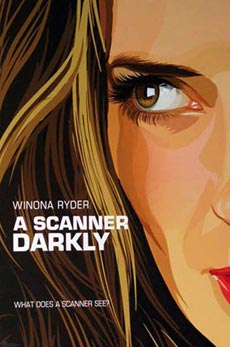

- Reeves/Arctor wakes up, and finds himself next to a woman whom he had enticed into his bed with the offer of drugs; as she sleeps, her body metamorphoses into that of Donna (Winona Ryder) the unattainable woman (she wont let him touch her) Arctor really desires and then back again. Arctor goes to the surveillance room, and (as Fred, in a scramble suit) watches the incident on video replay and the momentary metamorphosis takes place on the tape as well. The hallucination has been objectified: it plays out for the scanner, as well as for Arctor.

How are to read this, the pivotal scene of the film? It is almost as if the scanners have acted as analysts, exposing the Real of Arctor’s desire for Donna. (‘To love an atmospheric spirit. That was the real sorrow. Hoplessness itself. Nowhere on the printed page, nowhere in the annals of man, would her name appear: no local habitation, no name. There are girls like that, he thought, and those you love the most, the ones where there is no hope because it has eluded you at the very moment you close your hands around it.’) Or as if the surveillance machines – the means, supposedly, by which we verify whether an event has happened or not – have themselves begun to fantasize. In any case, this moment of ontological scrambling is the ‘wound in Being’ into which the film and the novel both implode.

In a McDonalds franchise, Donna and Mike discuss damnation:

- “I’m going to hell,” …

“In hell they sell you nickel-bags and when you get home there’s M-and-M’s in them.”

“M-and-M’s made of turkey turds,” Donna said, then all at once she was gone.

Death to New-Path…