… magical and unreal, and yet necessary…

Fri. March 16, 2007Categories: Abstract Dynamics

Further to my remarks on the musical in my post on Brecht, Matthew Moore writes:

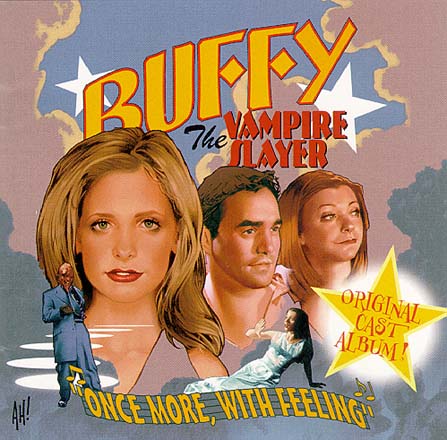

- In the musical episode of Buffy, “Once More With Feeling”, the characters are only honest with each other when they are possessed by the Spirit of The Musical. By Song. Whilst this might sound like a trad version of Singing Voice = Unmediated Truth it doesn’t play out that way. The unveiling of feeling through song is not positive – there is no Singing Cure – but leaves the characters more lost, bitter & confused than at the beginning. The Song here is literarally something demonic & unnatural – and destructive (if you sing & dance for too long, you spontaneously combust). This happens in Season 6 of Buffy – which is all about becoming an adult with the compromises & decisions that entails. Song is something unpleasantly Grown-Up, something that forces you to both say & hear you do not want to. Which is a nice reply to the accusation that Musicals are infantile.

I confess that I haven’t seen ‘Once More with Feeling’, but this sounds very much like Pennies from Heaven and The Singing Detective, where the truth of the characters’ feelings and fantasies emerges in Song. Yet this truth cannot appear in its own right, but only as an interruption of the ordinary rules and conventions of realism (one way, perhaps, in which truth must appear in the guise of fiction). That was what fascinated me about Brecht’s take on songs – that, in the Musical, their role was to produce an ontological rupture, a break in realism’s entrancing imitation of life.

Pennies from Heaven is of course about the power of songs, and perhaps Arthur’s tragic fate is sealed once he seeks to make the two worlds – the world of everyday reality and the ‘world that the songs are about’ – co-incide.

In Edith’s Diary (which may well be her masterpiece), Highsmith produces a vivid description of music’s power to disrupt everyday life. Edith is a talented writer who has sacrificed her career to take on the roles of wife, mother (of a slacker misfit) and carer (to her husband’s helpless geriatric uncle). She uses music as a means of keeping the urgencies of everyday life – the relentless, Sysiphian ‘household flow’ of domestic tasks – briefly at bay.

- Edith put some Brahms waltzes (Opus 39) on the record player, and closed the living room door which went into the hall … She had lit a cigarette, and was relaxing in an armchair. The piano music delighted her, transported her to a world of beauty and brilliance – with a beginning and an end. It was odd to feel for a few seconds at a time – the sensation came and went – completely like the music, quite at home with it, familiar with every note, yet to realize that the music was not her home, was not the main part of her life. Sometimes, she thought music that she especially liked was a drug for her, magical and unreal, and yet necessary.

Unreal, and yet for many seconds the inspired waltzes made her love her house more, made her remember that the house and the semi-rural life she had now was after all what she had wanted for years. …

When the first side of the record was finished, the silence began to attack Edith like a live thing, eating away at her brief contentment. This was life, she thought, back to the ironing which she now did in the kitchen, back to thinking of where next she might send the article on recognising Red China. A vague depression crept through her, crepuscular, paralysing.

Notice the way that the word ‘home’ functions in two different ways: when Edith is ‘at home’ with the music she is momentarily transported out of her ‘home’ (‘the music was not her home’). Yet the narcotic effects of the music, which are uncanny, ‘unhomely’, cast for a while an enchanting glow on her domestic space, suspend the constant reproaches and dissatisfactions that her home, with its uncompleted and uncompletable myriad of tasks, customarily brings. Music is in excess of life, but it is also that which makes life possible (‘magical and unreal, and yet necessary’). Silence, meanwhile, is life – within a sentence, Highsmith moves from seeing silence as a ‘living thing’, voracious and predatory, to seeing it as life itself (‘this was life’).

Edith’s style of listening is somewhat old-fashioned. As I argue in the current issue of Fact, it is well-known that the discipline and drama of listening to an LP is anachronistic in postmodern conditions of ‘total flow’. The turntable is an antique object, the practice of turning a record over a lost ritual, arcane and archaic. (In club culture, it goes without saying, turntables remain central, but their role here is precisely to render records as part of a flow, not as a series of discrete objects.)

Edith’s foreground listening is a relic. More common now is the way that Edith’s son, Cliffie – a character who, to modern eyes, cries out to be diagnosed as autistic – uses music. Cliffie habitually plays a transistor radio in his bedroom, less because he wants to commune with the music, and more because he wants to mark a boundary, ward off others. This use of music – as a means of defence and of withdrawal – is facilitated by the Walkman and later the iPod, which further enable the integration of music and everyday life. Yet this at the cost of the heightened, magical, transformative power which Edith experiences in music – because that power depends upon music being used as an interruption of the quotidian. Instead of enhancing everyday life, music has increasingly become part of everyday life, consumed and compromised by its banality.

Anahid Kassabian (via blah-feme) talks of an era of ‘ubiquitous listening’. Kassabian reports that, ‘[m]any of my students (and my daughters baby-sitters) leave the radio or MTV on in different rooms, so that they are never without music. They say it fills the house, makes the emptiness less frightening.’ Music’s ubiquity extends far beyond music programming, evidently; pop is now an omnipresent background in soap operas, documentaries and advertisements alike (at the moment, Razorlight are a particular favourite on British TV, and it is practically impossible to watch television for any length of time without being confronted with their dull meat and potatoes indie grind.) Music, deprived of any ‘scene’, any special context or staging, is fully integrated into what Baudrillard called ‘the ecstasy of communication’. Must we then speak, as blah-feme suggests, of an ‘end of music’? Not because music has disappeared, but because, on the contrary, it is impossible to avoid.