Look at the light

Wed. November 16, 2005Categories: Abstract Dynamics

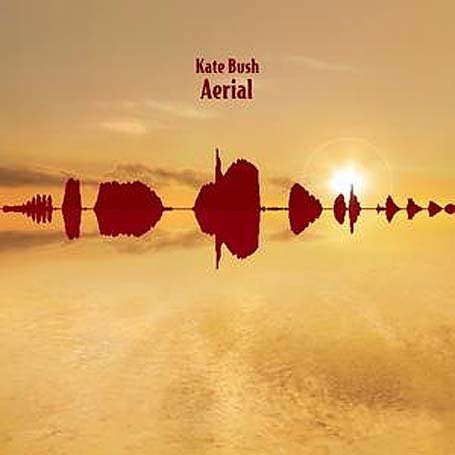

Its cover image is a waveform of a blackbird’s song re-imagined as a geological formation. Kate Bush’s Aerial is Deleuzian MOR: a numinous, luminous twitterscape of women-animal becomings, a hymn to light, and lightness.

I’d concur with what’s already coalescing into a critical consensus: ‘King of the Mountain’ apart, the first disc – ‘Sea of Honey’ – is merely an appetizer for the second CD, the sumptous song suite that is ‘A Sky of Honey’.

On the face of it, for this, her return after twelve years, Bush could either make a show of pursuing Relevance a la Bowie, or Madonna, or else recline into a session-musician airbrushed ‘timelessness’ like Bryan Ferry. In the event, she tacks closer to the second option, but with considerably more success than Ferry has mustered in any of his solo albums for the last twenty years. The sonic pallette from which Bush has constructed Aerial contains few rogue elements, and hardly anything that would have discomfitted a mid-80s audience.

And yet … ‘A Sky of Honey’ in particular has the flavour, if not the instrumentation, of later genres. The intermittent birdsong, the lambent washes of subdued strings and synth, the shifts in atmosphere – now tranquil, now tempestuous, now humid, now temperate – recall ambient jungle (I’m put in mind more than once of Goldie’s ‘Mother’), the lush opiated vastness of microhouse, English pastoral techno such as Ultramarine.

It is in A Thousand Plateaus‘ ‘Of the Refrain’ that Deleuze and Guattari write of birdsong. On one side, the refrain is a territorial marker, the tracing of an interiority; on the other, it opens out into the cosmos. Aerial is similarly double: ‘A Sea of Honey’ exploring the heimlich, ‘A Sky of Honey’ dreaming the cosmic.

‘King of the Mountain’ has been one of the singles of the year – insidious and insinuating rather than immediate, a blind-side seduction which makes itself a habit before you’ve registered awareness of it. Its snowswept eyrie contains the grandest, most elemental, rendition of the twin themes that dominate ‘A Sea of Honey’ – domesticity and isolation. Kane in Xanadu doubles Elvis in Graceland, wind howling around the melancholy opulence of their empty mansions.

The other songs on ‘A Sea of Honey’ retreat from these media myth-scapes into more intimate territory. Bush flirts with sentimental indulgence on the song addressed to her son, ‘Bertie’, while meditating on the line between bliss and banality, pathos and bathos, on ‘How to be Invisible’ and ‘Mrs Bartolozzi’, with their imagery of anoraks, wallflowers and washing machines.

What is fascinating about ‘Sea of Honey’ is its exploration of the Mother’s bliss, which has by definition been excised from a history of rock that has endlessly staged the cutting of the apron strings, the rejection of the maternal. There’s something oppressive and cloying about this domestic space, something suffocating and greedily insatiable about the protected interiority Bush creates. The ‘domestic idyll’ is literally agoraphobic, troubled by an Outside it seeks to keep at bay. ‘How to be Invisible’ is a spell in which ultra-ordinary objects are brandished as protective charms, preservatives of a domesticity that has withdrawn from the wider social world. Yet the heimlich, the homely, is always, also, the unheimlich, the unhomely, the uncanny. In ‘Mrs Bartolozzi’, a widow’s solitude transforms laundry into a Svankmajer erotic dance, the boredom, loneliness and sadness of a confined mind transfiguring empty clothes into an animist memory-theatre. In these circumscribed horizons, washing the floor becomes a religious observance, an act of mourning and melancholy.

If ‘A Sea of Honey’ is a kitchen-sink delirium, its spaces all carpeted and walled, then ‘A Sky of Honey’ is widescreen, panoramic, as the words of the stand-out track, ‘Nocturn’, have it. Everything opens out. It’s as if we leave the artificial cocoon of the house to step out into the garden, a garden which becomes a lush Ernst jungle…

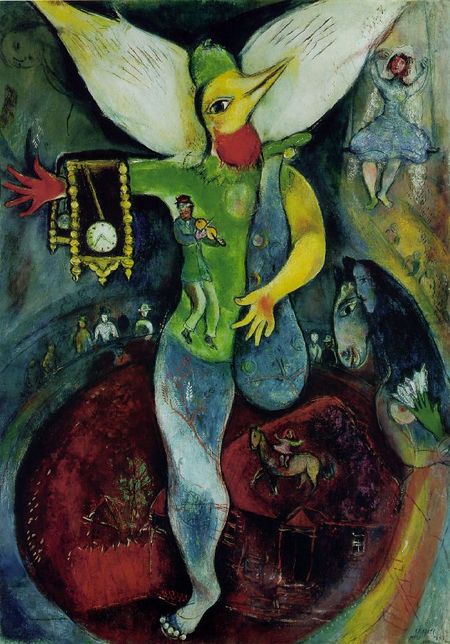

What impresses most about ‘A Sky of Honey’ is the majesty of its composition. It sounds like the sort of thing Bush has done before, but there’s nothing else in her oeuvre quite so sustained as this. I mean ‘composition’ in the painterly at least as much as the musicianly sense, for ‘A Sky of Honey’ is Bush’s most painterly record: each sound a delicate stroke in a delicately constructed and minutely conceived picture. Van Gogh (‘the flowers are melting!’), Chagall, Ernst, as much as Joyce or Bronte, seem to be the guiding hands. The painter’s medium – light – may well be ‘A Sky of Honey’s’ principal preoccupation. The image of a pavement artist’s work destroyed by rain is central to ‘A Sky of Honey’: ‘all the colours are running’. Yet no mood of regret or melancholy can last long here; in an instant, Bush is celebrating ‘the wonderful sunset’ that the run colours have become. Ironically for a record so artfully and fastidiously designed, so foreign to rock and jazz’s spontaneity, the message is that the Accident is the pre-eminent form of creation. We are gently urged to revel in the innocence of becoming, to ‘look at the light… and all the time it’s a changing….’ The record celebrates the butterfly-wing fragility of the Moment, the never-static Hacceities Nature is madly composing and is composed of, the ever-evanescent irridescences of the ‘somewhere in-between’ in which we are always lost. Between wakefulness and sleep, between land and sea, between sky and dust, between day and night, ‘A Sky of Honey’ reaches its poised, anti-climax plateau on the last three tracks, ‘Somewhere in Between’, ‘Nocturn’ and ‘Aerial’. By ‘Somewhere in Between’, we have reached dusk, the time when everything de-substantializes, and the song is a dance of dying light, a savouring of the evening’s bewitched, betwixt state. ‘Nocturn’ is up there with anything she’s done – its oneiric, oceanic disco a kind of becalmed answer to Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’, the white water of Smith’s angsts and passions soothed and smoothed into a placid lake in which amphibious longings swim and commingle. ‘Nocturn’ is a journey to the end of the night very different to the one Celine took: a Van Gogh-visionary stretching, a reaching both up into the sky and down into the sea.

‘The stars are caught in our hair/ The stars are on our fingers/ A veil of diamond dust/ Just reach up and touch it/ The skys above our heads/The seas around our legs/ In milky, silky water/We swim further and further/ We dive down… We dive down…’

There are suggestions of Joyce’s Anna Livia Plurabelle here, the river heading out to the sea that will swallow it, just as the dreaming mind awakens. After this, there is the dappled return of sunlight on ‘Aerial’, glimmers of light on the water’s surface, ‘all of the birds laughing’, Bush joining in.

Magisterial, and better with every listen.