Image management in the Imperium

Thu. January 18, 2007Categories: Abstract Dynamics

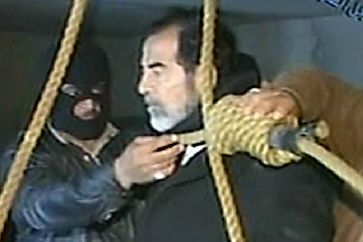

There is no better illustration of American cultural entropy, of the sense that things have finished but they continue to grind on, than Saddam’s execution. The scene is appalling, of course, in the way that all executions must be: the contrast between the quotidian dreariness of the surroundings and the terrible metaphysical threshold over which the executed individual must pass; the squalid brutality of the act of pre-meditated killing, which remains brutal and squalid no matter how atrocious the crimes of the condemned were. Films of live death are attempts to screen the Real, but, inevitably, the Real of death cannot be captured. What we are left with, instead, is another reality TV moment, recorded on mobile phone videocamera and distributed by YouTube. It begins with Shock and Awe and ends in Snuff…

The significance of the sounds and images of Saddam’s execution resides in what is absent from them: namely, any sense of ceremony. The images confirm the impression that, far from being the gleaming citadel of a nascent democracy (even Bush has given up on that pretence) Iraq is given over to casual atrocity, lynching and civil disorder.

The execution is a reminder that the American-led invasion of Iraq has singularly failed to produce any images that possess Symbolic efficacy. There is very far from being any equivalent of the flag-raising at Iwo Jima: an image powerful enough to itself constitute an incorporeal transformation. The scenes of Saddam’s statue being felled, all too obviously staged, played like a weak echo of similar, more powerful, scenes at the close of the Cold War.

The failure of image management is no trivial matter. We might go so far as to say that this alone indicates the final failure of the Neo-Conservative project, which, after all, was supposed to be about generating popular images and myths. No image which the US military-industrial-entertainment complex has produced in the last half decade can compare even remotely with the TV pictures of the twin towers collapsing, which remain – by some distance – the most significant semiotic event of the century. Instead of countering 9/11, indeed, the images of US bombing raids on Afghanistan and Iraq seemed to belong to the same symbolic moment. Rather than some succesfully stage-managed US photograph, it is the improvised Snuff of Abu Ghraib which has come to represent the campaign in Iraq. Saddam’s execution may have been intended as a moment of closure, but it signalled quite the opposite: the horrors continue. The images of Saddam being taunted by hooded figures horribly rhyme with the Abu Ghraib pictures.

With Saddam, it is as if the object of the Americans’ desire receded every time they closed in upon it. The first time they caught him, a bewildered old man cowering in a hole in the ground, the very radicality of the desublimation counted against the Americans perhaps even more than against Saddam himself: surely this could not be the personification of Evil that the war had been waged against? In this case, Saddam was too dehumanised to serve as the proper object of avenging American justice. But the execution produced the opposite effect: it did what the spectacle of executions cannot fail to, it humanised Saddam, all the more effectively because of his stoic demeanour in the face of the taunts of his tormentors.