I’m lost, you got me looking for the rest of me…

Thu. August 17, 2006Categories: Abstract Dynamics

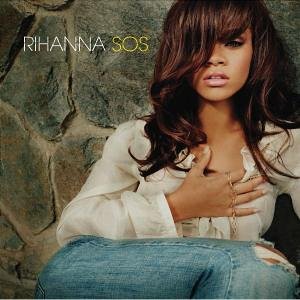

I almost missed one of this year’s great songs about obsession, Rihanna’s ‘SOS’. It nearly passed me by because my initial encounters with the song came via the video. The punitive predictability of R and B* promos (interchangeable digitally-slicked flesh endlessly rolling off an editing suite production line) repels interest, so I paid little heed to ‘SOS’ – ‘Tainted Love’ sample notwithstanding – when it came out a few months ago.

My interest in ‘SOS’ was piqued by Rihanna’s follow-up single, the fabulously overblown ballad, ‘Unfaithful’. ‘Unfaithful’ is a ballad in a quaint and apparently outmoded sense, in that it is about regret, pain and responsibility rather than getting it on. But listening back to ‘SOS’, you realise that it, too, is not so much about carnality as the pathology of love.

‘SOS’ ingests the sonic substance of the Soft Cell version of ‘Tainted Love’ – the familiar coldly addictive electronic bass line and subway-at-night synth stabs – but remotivates it. (Interesting to note that ‘SOS’ returns ‘Tainted Love’ to a black woman, the song having passed from Gloria Jones to Soft Cell – I’m ignoring Marilyn Manson, obviously.) The toxicity in ‘Tainted Love’ came from betrayal and infidelity, love turning sour; with ‘SOS’ love itself is inherently poisonous: ‘it’s not healthy… for me to feel this way… it don’t feel right’. If there is betrayal in ‘SOS’, it is (implicitly) Rihanna who is doing the betraying (the ‘don’t feel right’ suggesting moral corruption as well as love’s dis-ease).

‘Tainted Love’ was about the struggle between the desire to remain intoxicated by love’s sweet sickness and the wish to throw the monkey off the back. There was more than a hint that the grandstanding, climactic declaration – ‘now I’m going to pack my things and go’ – was bravado, a statement made without meaning it, or made only in front of the mirror. The very form of the song, the very fact that the wronged lover is still addressing the betrayer, indicates that the fixation remains. The threat of leaving is still a demand addressed to the lover who is supposedly being rejected. The truth of ‘Tainted Love’ is no doubt contained in the line ‘I love you though you hurt me so’ except that the line should read, ‘I love you because you hurt me so….’

The form of the love song is often that of a letter which is not sent, or should not be sent. (The psychosis of David Kelsey in Highsmith’s This Sweet Sickness is that he has no concept that could be such a thing as a letter that should not be sent, a feeling that should not be symbolically transmitted.) The most powerful love songs always turn on the discrepancy between the act of declaring love and the knowledge that the ostensible addressee is no longer there, was never there, and could never be there. Everyone knows that people continue to write letters or to talk to lovers long after the loved one is dead. But, very far from being unusual, this is the reality of erotic love laid bare. To give up the fantasy that there is someone there listening is far harder than giving up the object itself. The converse of this is the horror of receiving love letters or declarations of love: we know is that they are never really addressed to us.

‘SOS’ retains the theme of obsession, but, unlike ‘Tainted Love’, ‘SOS’ is about the head-over-heels, early stages of love. The willing submission to love’s vertiginous sickness is an encounter with the hole at the heart of subjectivity : ‘I’m lost/ you got me lookin’ for the rest of me’. The contest between love and the subject is always unequal: ‘Love is testing me but still I’m losing it’. Check the way in which Rihanna gives sibilant voice to a phrase like ‘stressing, incessantly pressing’, and the leering way she delivers the line (a steal from the ‘Tainted Love’ lyrics, of course) ‘toss and turn/ can’t sleep at night’. It as if she is the voice of the maternal superego, which knows that its demands to ‘enjoy’ can never be met, and which gains its own enjoyment from witnessing our torment. (Perhaps it is oddly fitting, then, that ‘SOS’ should have been used by Nike: lovesickness as an analogue for ‘the sheer explosive pointlessness of capital itself‘?)

Releasing ‘Unfaithful’ as the next single make it seem like the next instalment in a story. It’s a few months later; the dizzying allure of the affair has dissipated, and Rihanna is overcome by guilt. Both she and the lover she has betrayed know she has being having an affair, although this knowledge remains unspoken: ‘And I know that he knows I’m unfaithful/ And it kills him inside..’ (I pause to note that ‘Unfaithful’ is just about the only record by a contemporary black female to be have made the Radio 2 playlist in the last few months – there’s plenty of Razorlight and Snow Patrol, naturally.)

‘Unfaithful’ is remarkable for its gloriously unselfconscious, baroque sense of drama – like a muted Jim Steinman production, if you can imagine such a thing. ‘I don’t wanna do this any more/ I don’t wanna take away his life/ I don’t want to be…. a murderer….’ It is remarkable also because it has a woman assuming the role of betrayer. If ‘SOS’ was about the jouissance of losing one’s autonomy, ‘Unfaithful’ is about belatedly taking responsibility. ‘On a lot of records,’ Rihanna says, ‘men talk about cheating as though it’s all a game. For me, “Unfaithful” is not just about stepping out on your man, but the pain that it causes both parties.’

‘SOS’ was turned down by Christina Milian, and Rihanna now emerges as the most serious rival to both Milian and Beyonce. (She shares their notorious work ethic: her latest album, A Girl Like Me is Rihanna’s second in less than a year.) Rihanna, a mere 18, wants to position herself as ‘having a personal conversation with girls my age. My goal on A Girl Like Me was to find songs that express the many things young women want to say, but might not know how.’ Certainly, there is a space for female desires and anxieties on Rihanna’s record that is missing on Milian or Beyonce’s recent records. The persona Milian projects in her songs – witness her absolute mistresspiece, ‘I Can Be That Woman’ – is passive to the point of abjection. Beyonce, meanwhile, has moved from singing clever songs about ambivalence and the failings of men to subordinating herself utterly to a caricatured male desire. She is now either the devoted Soul sister cooing bland syrup (a la most of the last Destiny’s Child album) or the pneumatic sex machine who will do anything for her man.

The significance of the subjective position adopts in ‘Unfaithful’ is that it is about both female desire and responsibility. Even the preposterous self-assertion of something like Destiny Child’s ‘Survivor’ stilll assumed a woman that, although undefeated, was wounded by a man, and who still addressed her statement of triumph to the man who had underestimated or dismissed her. ‘Unfaithful’ is peculiarly touching because it is not addressed to a man at all; it is written in the third person, as if Rihanna is talking to a friend about what she has done. The real addressee of ‘Unfaitfhful’, of course is the big Other. Perhaps it is only in the third person, when the fantasm of reciprocity is set aside, that expressions of love can pass beyond narcissism.

* Strictly speaking, it is perhaps a little misleading to describe Rihanna’s sound as R and B. Even though Jay-Z is executive producer on A Girl Like Me, the album is thankfully free of the rap cameos that blight most R and B. Indeed, A Girl Like Me, which has – to my ears – at least eight possible hits on it, holds open the utopian possibility of a black music liberated from the dead phallic weight of hip hop. A Girl Like Me‘s mixture of electro, dancehall, old skool skank and R and B makes it something like a Cupid & Psyche 2006. It isn’t the sadness of some of the songs that makes the album unique; it is their ambivalence. Check the next single, ‘We Ride’, for instance, a superficially summer-breezy tune that turns out to be freighted with conflicted longings.