How the Other Half Doesn’t Live

Sun. September 20, 2009Categories: Abstract Dynamics

- 1: Woman sawn apart in a wooden crate, wearing a bathing suit, smiling, a trick done with mirrors, I read it in a comic book: only with me there had been an accident and I came apart. The other half, the one locked away, was the only one that could live; I was the wrong half, detached, terminal. I was nothing but a head, or no, something minor like a thumb; numb.

- 2: Pleasure and pain are side by side they said but most of the brain is neutral: nerveless, like fat. I rehearsed emotions, naming them: joy, peace, guilt, release, love and hate, react, relate; what to feel was like what to wear, you watched the others and memorized it. But the only thing there was the fear I wasn’t alive: a negative, the difference between the shadow of a pin an what it’s like when you stick it in your arm, in school caged in the desk I used to do that, with pen-nibs and compass points too, instruments of knowledge, English and Geometry; they’ve discovered rats prefer any sensation to none. The insides of my arms were stippled with tiny wounds, like an addict’s. They slipped the needle into the arm and I was falling down, it was like sinking from one level of darkness to a deeper, deepest; when I rose up through the anesthetic, pale green and then daylight, I could remember nothing.

- 3: I didn’t feel awful; I realized I didn’t feel much of anything. I hadn’t for a long time. Perhaps I’d been like that all my life, just as some babies are born deaf or without a sense of touch; but if that was true I wouldn’t have noticed the absence. At some point my neck must have closed over, pond freezing or a wound, shutting me into a head; since then, everything has been glancing off me, it was like being in a vase, or the village where I could see them but not hear them because I didn’t understand what was being said. Bottles distort for the observers too: frogs in the jam jar stretched wide, to those watching I must have looked grotesque.

Dysphoria screams quietly out of Margaret Atwood’s Surfacing. In some respects, Surfacing, published in 1972, could be seen as registering the bitter awakening after the militant euphoria of the Sixties, Atwood’s famously cold prose freezing over the Sixties’ heated loins, and drawing, from the semi-desolation of the Canadian bush, a new Cold World landscape as alluring and forbidding as any in literature. A conservative reading suggests itself – what surfaces here, it might seem, are the consequences that Sixties permissiveness imagined it had dispensed with. The repressed – which in this sense would mean the agencies of repression themselves – returns in the spectral form of the unnamed narrator’s aborted child, encountered in a dark lake space where excrement and jellyfish-like foetal scrapings float, the abjected and the aborted commingling in a sewer of the Symbolic. Far from enabling her to ‘regain’ some ‘wholeness’, the reintegration of this lost object destroys the fragile collage of screen memories and fantasies the narrator’s unconscious has artfully constructed, projecting her from the frozen poise of dysphoria into schizophrenia – which, in the conservative reading, would constitute a proper punishment for her licentiousness.

There’s a great deal at stake in resisting this conservative reading, and I think it takes us to the heart of what is so valuable in the concept of a militant dysphoria. Certainly, Surfacing savagely deflates the pretentions of the counterculture, which Atwood’s narrator remorselessly eliminates, exposing a libertarian-misogynistic “Americanism” underneath. “I could see into him, he was an imposter, a pastiche, layers of political handbills, pages from magazines, affiches, verbs and nouns glued on to him and shredding away, the original surface littered with fragments and tatters. … Second-hand American was spreading over him in patches, like mange or lichen.” In his recent LRB review of Atwood’s The Year Of The Flood Jameson admiringly cites one of the anti-American fulmination which punctuate Surfacing. Yet it should be remembered that Atwood cooly ironises the anti-Americanism of her characters by having the swaggering boors that they had imagined to be American turn out to be fellow Canadians – Canadians who had themselves thought that the narrator’s group were Americans. Everyone – it appears – is Americanised now, none more so than these hip(pie) longhairs spouting anti-American rhetoric.

If Surfacing rejects the facile gestures of an exhausted, narcissistic counterculture, there is no question of its endorsing the (apparently) safe and settled world which the counterculture repudiated. That world of supposedly organic solidity – her parents’ world, where people have children who grow like flowers in their back garden, the narrator imagines – is gone, Atwood’s narrator notes, with an edge of witstfulness that nevertheless stops somewhat short of nostalgic longing. What remains is not any politics rooted in an actual lifeworld, but a politics of the Cold World. The question that Surfacing poses, and leaves hanging, is how to mobilise dysphoria rather than treat it as a pathology that requires cure – either by successful reintegration into the Symbolic/ civilization or by some purifying journey out beyond the Symbolic into a pre-linguisitic Nature. How, in other words, is it possible to keep faith with, rather than remedy, the narrator’s affective dyslexia?

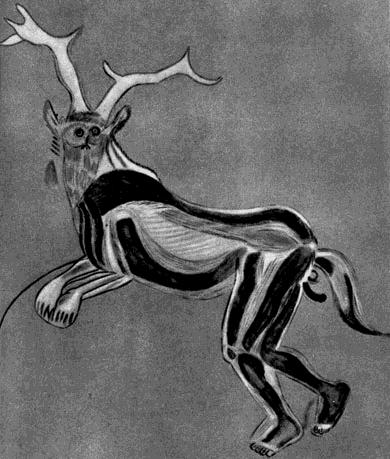

Surfacing belongs to the same moment as Baudrillard’s Symbolic Exchange And Death, Lyotard’s Libidinal Economy, Irigaray’s Speculum: Of The Other Woman – and Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus. Though it is A Thousand Plateaus that Surfacing most obviously prefigures – yet what separates Surfacing‘s “terrifying Deleuzian devenir-animal” (Jameson) from Deleuze and Guattari is precisely Atwood’s refusal of affirmation(ism). At her moment of schizophrenic break-rapture, the narrator certainly sounds like a good Deleuzean: “they think I should be filled with death, I should be in mourning. But nothing has died, everything is alive, everything is waiting to become alive”, but this febrile delirium is more in tune with Ben Woodard’s “dark vitalism” than Deleuze, and what flows and stalks in the body-without-organs zone of animal- and water-becomings is something like Ben’s sinister “creep of life”. “I hear breathing, witheld, observant, not in the house but all around it.” The place beyond the mortifications of the Symbolic is not only the space of an obscene, non-lingustic “life” but also where everything deadened and dead goes, once it has been expelled from civilization. “This is where I threw the dead things…” Beyond the living death of the Symbolic is the kingdom of the dead. “It was below me, drifting towards me from the furthest level where there was no life, a dark oval trailing limbs. It was blurred but it had eyes, they were open, it was something I knew about, a dead thing, it was dead.”

Surfacing can be situated as part of another fin-de-Sixties/ early 70s moment: the post-psychedelic oceanic. Atwood’s lake, viscous with blood and other bodily fluids, has something in common with the “bitches brew” that Miles plunges into in 69, emerging, catatonic, only six years later; it approaches the deep sea terrains John Martyn sounds out on Solid Air and One World. “Pale green, then darkness, layer after layer, deeper than before, seabottom: the water seemed to have thickened, in it pinprick lights flicked and darted, red and blue, yellow and white, and I saw that they were fish, the chasm-dwellers, fins lined with phosphorescent sparks, teeth neon. It was wonderful that I was down so far…” But these spaces of dissolved identity are not approached from the angle of a now tortured, now lulled male on a vacation from the Symbolic, but from the perspective of someone who was never fully integrated into the Symbolic in the first place.

Surfacing, like the later Oryx And Crake, is a kind of rewriting of Civilisation And Its Discontents – the text with which all that early 70s theory had to wrestle, and reckon. Just as at the end of Oryx And Crake, Surfacing concludes with a moment of suspension, with the narrator, like Oryx‘s Snowman, poised between the schizophrenic space beyond the Symbolic and some return to civilisation – is this suspension not the proper place of the dysphoric militant? Perhaps what is most prescient about Surfacing is its acceptance that civilization/the big Other/ language cannot in the end be overcome and overwhelmed by means of libido, madness, mysticism or whatever other weapons the militant euphorics had thrown against it – yet, despite all this, Surfacing does not recommend an acquiescence to the reality principle. “For us, it’s necessary, the intercession of words,” the narrator concedes – but who is this “us”? It seems at first to encompass only the narrator and the lover with which she may be about to be reconciled. Then we might be tempted to read the “us” as humanity in general, and the novel would be ending with a fairly cheap reconciliation between civilisation and one who was discontented with it. Yet it’s more interesting to think of the “us” as indicating those, like the narrator, who do not properly belong to humanity at all – what kind of language, what kind of civilisation, would these discontents make?

- He calls for me again, balancing on the dock which is neither land nor water, hands on his hips, head thrown back and eyes scanning. His voice is annoyed: he won’t wait much longer. But right now he waits.

The lake is quiet, the trees surround me, asking and giving nothing.