He was the man-ager

Mon. June 9, 2008Categories: Abstract Dynamics

|  |

- Smith had wanted the book to read like the autobiography of a football manager: ‘like Malcolm Allison’s’. A key part of his job, as he sees it, is to take apprentices and mould them into Fall musicians, firing them as they become complacent or take on airs.

These comments by Nicholas Blincoe about Mark E Smith’s ‘autobiography’ substantiate many of Owen’s observations on Mark E Smith and management. Smith has made the analogy before, in this Guardian piece:

- Running the national football team is very much like running my group, the Fall. As a manager, you’ve got to maintain a certain detachment from your players, and it’s the same with my musicians. When we’re on tour, I sit at the back of the bus. We’re friendly but the secret of it is never get too ally-pally.

The obvious football manager parallel for Smith has always been Brian Clough (mentioned in passing in Renegade as it happens) – both representatives of a fierce Northern working class intelligence, both capable of dominating and beguiling others with their charisma and their will, both achieving their greatest successes at the end of the 70s and the beginning of the 80s (Clough winning the European cup in successive seasons, Smith releasing Dragnet, Grotesque and Hex Enduction Hour); and both ultimately sinking into alcohol soaked degeneration. Another parallel is their troubled relationship with collaborators: the extrovert Clough never won a major honour without the anxious, cautious Peter Taylor by his side, his shadow, the supplement without which he was never fully himself (and who, accordingly, he both loved and hated). Smith, meanwhile, has been more likely to depend on women: as the Blincoe piece suggests, it’s no accident that Smith’s greatest moments coincided with the time that Kay Carroll managed the group.

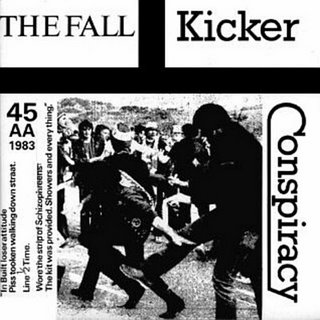

Reading David Peace’s incantatory The Damned United recently – a book I’d avoided until then for all kinds of strange reasons: Clough and Peace together! A combination so irresistible to me that I resisted it – I was repeatedly reminded of the line from The Fall’s “Kicker Conspiracy”: “how flair is punished”. They hate flair here, Clough reflects when he arrives in the cursed heartland of Peace’s Yorkshire to begin his short (ill fated) tenure as manager of Leeds. It’s not clear who was more perverse – the Leeds board for offering the job to Leeds’ and Revie’s most outspoken critic or Clough for taking it.

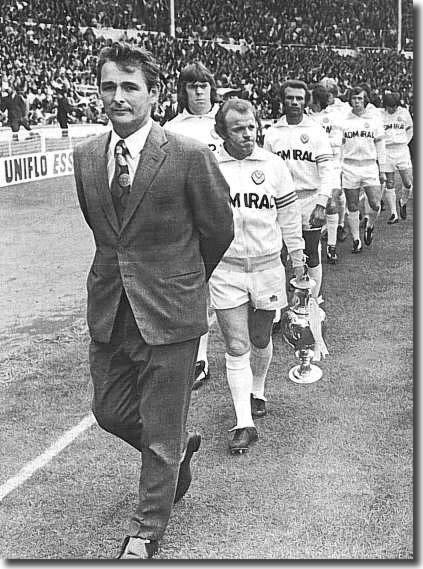

Look at the photograph of Clough leading out the Leeds team at the 1974 Charity Shield at Wembley, his first game in charge (a doctored version of it is on the front of Peace’s book): their shoulders sloped, their faces grim, many of them looking older than Clough himself, the players already appear defeated, confirming Clough’s judgment that they were past it. Look at Billy Bremner, just behind Clough, his face contorted into a rictus of rage and resentment – but directed at whom? Clough? His departed mentor, Don Revie? Himself? The then present and the future, which held only disappointment and decline? We get no answers from Peace’s book, which, cleverly, claustrophobically, is focalised entirely through Clough, amplifying his sense of isolation and estrangement to the point where it quickly becomes unbearable. Bremner – who, in some of the saddest scenes in Peace’s novel, Clough makes a futile attempt to cultivate – remains a black box, a taciturn malignity, his ultimate motives imponderable, veiled by a blank mask of hostility. Whatever the causes of Bremner’s anger that day, he took it all out on Kevin Keegan, provoking the Liverpool striker into an act of retaliation which would end, notoriously and scandalously, in their both being sent off: black Yorkshire clouds already gathering over Clough’s reign.

The Damned United is in part about different sorts of resentment. The glowering resentment of Leeds against Clough versus the sense of resentment that burns in the young manager. Clough’s managerial career is envisaged as an act of revenge for the injury which prematurely, tragically, curtailed his playing career. Finished for ever. Second best. For ever… This is how you shall live – in place of life, a revenge. But revenge against whom? Why, Fate of course… The Fate in which Clough refuses to believe. ‘I don’t believe in luck’, you tell Don. ‘And I don’t believe in God.’

The Damned United is also, of course, about different types of management, with Clough’s existentialist rationalism – I don’t believe in luck, I’m a socialist – set against his arch rival Revie’s neurotic voodoo. Peace’s Clough understands the mechanics of hyperstition: if you believe in luck, then you will fall prey to the Signs, your destiny will slip from your own hands. (Revie’s Leeds ‘unluckily’ lost out on winning the championship on the last day on several occasions, once to Clough’s Derby in 1972.) Don Revie made them believe in luck, made them believe in ritual and superstition, in documents and dossiers, in bloody gamesmanship and fucking cheating, anything but themselves and their own ability. Whereas Clough and Taylor thought that you can’t win unless you believe you can win. The point was to instill self-belief.

This is bloody good management. This is you and Pete at your best –

Spotting the talent, buying the talent and then handling that fucking talent –

Insulting that talent. Humiliating that talent. Threatening that talent.

Hurting that talent and then kissing it fucking better again –

Again and again, bringing out the bloody best in folk –

In that fucking talent, that’s you and that’s Peter.

There’s no better example of the way in which success in football depends on management than Clough and Taylor. Clough and Taylor – who, remember, took a backwater Second Division club, and made them into League champions, not once but twice, with players, for the most part, that no-one else wanted or could do anything with. No accidents, no luck, this was real sorcery, not hocus pocus. No player was a greater testament to their approach than John McGovern – who makes a brief, sad appearance in The Damned United, the time and the place not right for him. McGovern seemed destined to be a middling journeyman professional, but with Clough and Taylor’s help he cheated that destiny and ended up winning two league championships (one with Derby, one with Forest), and two European cups. No accidents, no luck.

Being a good manager is about being an engineer of collectivity; not about assembling the best players but about getting the best out of the ones you’ve got. There’s nothing supernatural about esprit de corps, although any team that it has it will seem to have (at least one) extra player. Compare Smith’s remarks on the England team again:

- The way the England team is now is ridiculous. A team of superstars is like a supergroup. It’s like picking the best guitarist in Britain, the best drummer and the best singer, and expecting them to produce something that isn’t prog-rock mush. It doesn’t work: this England team will never work at the highest level. I know that. See, Sir Alf Ramsey – people never liked him for it, but he’d always have the full-backs from the second division. He took players and moulded them, like I do with musicians. Gordon Banks, the goalkeeper, was from Stoke City, who were bottom of the first division.

At a certain point, though, the sorcery stops working: self-belief becomes arrogant hubris, motivational techniques become mere bullying, everything dries up, apart from the drinks, which keep on coming. The fearless leader who inspires loyalty becomes the drunken Lear surrounded by sycophants. It happened to Clough, it happened to Smith.

If only Smith had a ghost writer as accomplished as Peace, who gets better the less he seems to do. The Damned United removes the thin veneer of anonymity and that kept GB84 (whose subject, Arthur Scargill – another Clough/ Smith analog – is never named) resembling a conventional work of fiction. But Peace’s art, like Gordon Burn’s in the recent Born Yesterday, is the skillful manipulation of facts as found objects. It’s anti-biography, mythography. Peace insinuates the grain of the Seventies into the weft of his prose, into its rhythms – he doesn’t shove period signifiers in your face in the way that clipshow-as-drama Life On Mars did.

Without wishing to lapse into the Rod Liddle eulogy for a lost era of working class football that Simon Sellars rightly excoriates, The Damned United reminds you of a time when proletarian managers could control football clubs by force of will. Ferguson is the last of that breed, but he is a relic, his control over United weakening, his long tenure a throwback to an older time. The puffed-up patricians who hounded Clough out of Derby have long since been replaced on the boards of football clubs by bland accountants representing corporate interests or pharaonic figures with vast personal capital available for potlach. The continuous upheaval of post Fordism has destroyed the long term in football, as everywhere else. In a perfect reflection of the general situation after thirty years of neoliberalism, the rich clubs have become richer, more remote, impervious. Derby, Forest or some other small club winning the Premiership is unthinkable. The grim Seventies – the Eastern Bloc as an era – has become a time of fairy tales.