Hauntology in Dublin

Thu. December 14, 2006Categories: Abstract Dynamics

|  |

To Dublin, then, where last week the National College of Art and Design held a one-day symposium on hauntology.

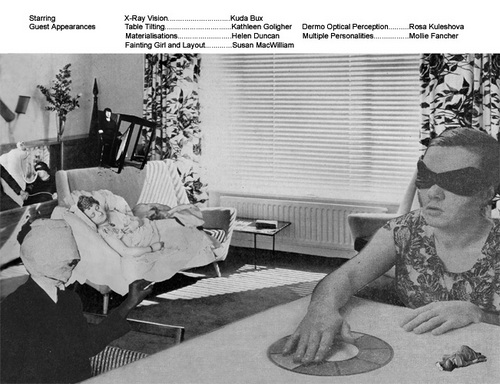

Highlights for me included Susan MacWilliam, who talked about a series of films and installations devoted to seances, telepathy and mediumship. Her piece, ‘The Last Person’, about Helen Duncan, the last person to be tried under the British witchcraft act, was impressively disgusting in its rendering of the phagic physicality of ectoplasm-channeling.

Brian Dillon, who amongst many other things is the UK editor of the excellent Cabinet magazine, spoke about a series of spaces to which he is compelled to keep returning, either actually or virtually: Dungeness, Herne Bay, Estonia. Brian’s fixation on these ‘old haunts’ was brokered by artists: Tacita Dean, who famously filmed the sound mirrors at Dungeness (to which Kode 9 and I made a pilgrimage a couple of years ago), and Jeremy Millar, who, after learning from Dean that Marcel Duchamp had visited Herne Bay while working on the Large Glass, made a film speculating on what the – inherently Dadaist – encounter between the young artist and the decaying Kent seaside town might have involved. (See Millar’s own account of the film here…)

Millar also visited Estonia, searching for the locations out of which Tarkovksy conjured the Zone in Stalker. Millar’s quest, inevitably, was met with some frustration, since much of the Zone was constructed on a set in Moscow. Afterwards, Brian and I talk about how Stalker was haunted by absences: the form the film currently takes was the result of the first print of the film decaying; a wholly different version – using the special effects so conspicuously lacking in the version that was released – had originally been shot. In addition, Tarkovsky had always to second guess the cuts that the censor would make. Tarkovsky made his films anticipating that they would be cut, but he could never be sure which sections would be lost.

Dungeness, which resembles the Suffolk coast near where I live now, is already reminiscent of the Zone: the rotting huts and shacks, the WWII relics, the brooding power station (as used in the Dr Who story The Claws of Axos in 1971 – and I note in passing that one of the things that is missing from the new Dr Who is any exploration of this kind of scurf space), the strange Picabia-like machines left on the beach like detritus abandoned by a departed civilization whose intentions are now opaque to us …

For the citizens of industrialized societies, there is a certain universality of the Zone. Most of us will have been captivated at some time by spaces dominated by derelict factories, burned-out vehicles and military/industrial technology wreathed in resurgent greenery. Such spaces strike a deeply resonant chord with the industrialized unconscious; indeed, they might be an image of that unconscious itself.

In any case, Brian’s presentation made me reflect that there is a room for a kind of hauntological travel writing; or that the best kind of travel writing is already hauntological, already a study of the power of place as a recording system (cf Lethbridge, or Kneale’s The Stone Tape). It also made me think, again, about the relationship of hauntology to place (one of the meanings of ‘haunt’ being ‘a place’, of course); and fantasise, again, about hauntological events which would take place in derelict or semi-derelict spaces.

|  |

I concentrated on sound, talking, as you would expect, about Burial, Little Axe, Ghost Box, Mordant Music and the Caretaker. My claim was that, in hauntology, there is the possibility of a positive alternative to postmodernity. Against the disavowed revivalism of postmodernity’s ‘nostalgia mode’, there are the spectres of lost futures. The ‘spectre that haunted Europe’ was not, after all, a returning revenant, but the avatar of the new, which could only be declared to never have arrived when Communism’s malevolent doppelganger, Stalinism, disintegrated at the end of the eighties.

A decade ago, it was possible to line up rave, jungle, techno and hip hop as alternatives to postmodernity and its discourses. Then, the language of recombination, rather than of spectrality, seemed most appropriate to deal with sampling. But now hauntology is revealed as belonging to the same moebian band as cyberpunk, and both can be opposed to the – linear, progressive – future that SF Capital projected. As Kodwo observes in ‘Further Considerations on Afrofuturism’:

The ‘founding trauma’ of the Black Atlantic involved the shattering of linear time: Apocalypse now (and forever). X marks the spot where identity was permanently erased; what is left is the absence, the memory loss, that is constitutive of Black Atlantean subjectivity as such. (Butler’s Kindred remains one of the most powerful explorations of the bind whereby, for the modern Black Atlantean, wishing away slavery means wishing away oneself.)

The ghost embodies dyschronia (it is the apparition of his father’s spectre, of course, which causes Hamlet to declare that the ‘time is out of joint’), even as it calls for revenge, reparation, for things to be set right (and for its raison d’etre to disappear). Yet hauntology must be about the enjoyment of dyschronia, about the unwillingness to set time back into joint. Ten years ago, the most apt image of dyschronia – in either its traumatic or its ecstatic modes, and these are not always extricable – would have been the future invading the past. Perhaps now, though, dyschronia is most strikingly encountered in the persistent traces of that which has never arrived, but which will never go away.

I ended with a discussion of The Caretaker, whom I still believe offers the most acute diagnosis of postmodernity as pathology. In lighting upon ‘theoretically pure anterograde amnesia’ as the name for our cultural condition, The Caretaker makes us realise that our problem is the inability to make new memories. Who would have suspected that nostalgia and amnesia were twinned in this way? But what is the nostalgia mode if not an amnesia of the present (and future)? (Amnesia of the present, naturally, is the complement to hauntology’s nostalgia for the future.)

We are the ghosts, now, in the Caretaker’s haunted ballroom; the melodic traces of familiar tunes are the fragments of the past to which we cleave in a hostile, abstract present that is unintelligible, unmappable. At this point, we must mention V VM’s other 2006 mega-project of mourning, The Death of Rave (available for download here): rave as revenant, reduced to reverberations. The Death of Rave can be heard as a supplement to the Burial album; another seance of the underground, another burned-out synaptic journey into rave’s lost Eternal Now, another delving the dank dilapidation of its deserted spaces… The temporality of The Death of Rave is that of the flashback, the irrruption of a lost future (from the near-past) into the present…

___________________________________________________________________

Dungeness features – amongst several other Zone analogues – on the tremendous Nothing to see here site (as recently linked to by Owen.

Speaking of space, architecture and related matters, I’ve been meaning for some time to link to another brilliant interview at Ballardian, this time with Geoff Manaugh of BLDNGBLOG. It may surprise people that I agree with Geoff about Crash, which I found difficult to read and incredibly obvious after the far superior Atrocity Exhibition. I also agree that ‘Id like to see Steven Spielberg direct The Drowned World as long as he didnt add any kids to the screenplay’. Surely, now is the time for an adaptation of The Drowned World; but this must be set in London. Whatever the merits of the adaptations of Crash, The Atrocity Exhibition and the upcoming High Rise, I’ve been disappointed that none were set in London. (Basic Instinct 2 is the best version yet of a Ballardian London.)