‘Father, can’t you see I’m burning?’ The death drive in X-Men: The Last Stand

Tue. June 6, 2006Categories: Abstract Dynamics

CONTAINS SPOILERS

|  |

There’s a great deal to be said about the tremendous new X-Men film, (and much has already been said, very well, in Josef K’s piece on Different Maps). By some distance the best film of the sequence so far, what is impressive about X Men: The Last Stand is that it dares to take itself seriously, avoiding the bad reflexivity of Pomo in favour of an unscreened exploration of a mythos. After all, the Pulp Unconscious of comics, populated by human-animal hybrids, is our closest equivalent to Greek or Roman myths, and thankfully, there is no Frank Miller style anti-mythic psychobiographical chin-rubbing in The Last Stand; this is not a film that tries to be ‘psychologically realistic’. No, it is a film about the Real, that which we flee from when we awake from a dream. Thus it takes place in the apocalypses we encounter every night, in the endlessly collapsing and reconfiguring blue-black landscapes of nightmare.

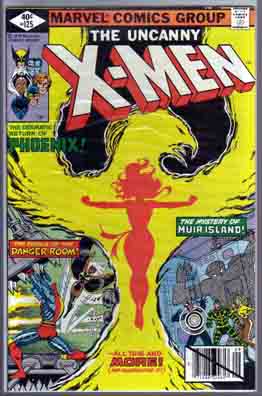

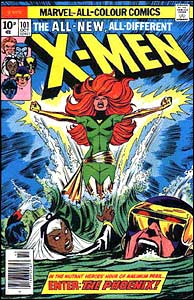

The Last Stand, like the New X-Men comics on which it is based, is dominated by the theme of death. (Long before the Phoenix story, on only their second mission, one of the New X-Men, Thuderbird, died in action.) Jean Grey had heroically died at the climax of the previous film, and The Last Stand risks bathos by having her return from the dead, as Phoenix. But any fears that the film would retrospectively cheapen the impact of the previous instalment by reviving Grey are quickly dispelled. The Last Stand is unwavering in its message that the return from is worse than death itself.

You may recall that last year that when I had to fill in a meme about what my superhero name would be, I, predictably, chose the name Death Drive. But Phoenix – not so much that which endlessly returns to life as that which cannot die – might as well be called Death Drive. In fact, you will not find a handier illustration of the distinction between the Death Drive and the desire to die than the opposition between Jean and Phoenix. Jean begs to die, whereas Phoenix is endlessly re-incarnating undead desire. Jean’s wish to die is precisely, then, a wish to resist the Death Drive, to cease to be the meat puppet slave-shell inhabited by impersonal, inhuman, unliving desire.

The film is not only about phyical but also subjective-death – what is ‘Jean Grey’ if she is taken over by this uncontrollable, implacable force? (Conversely, what are Magneto or Mystique without their mutant powers?) We learn, though, that there is no ‘Jean Grey’ the authentic Self, that the Jean Grey persona was itself always a ‘screen identity’ developed by Xavier to contain Phoenix. (And, naturally, all of our identities are negatively shaped by the deforming pulsions of the Death Drive.)

|  |

Josef K rightly draws attention to the sexualized nature of the mutations and the implicit Queer politics of the film. The most traumatic and genuinely disturbing scene comes very early on:

- The teenage Warren Worthington (the X-Man Archangel) has locked himself in a bathroom and is breathing heavily. He is trying to cut off his wings with some rusty scissors. His father demands that he opens the door, “You’ve been in there for over an hour!” A panicked act of attempted concealment ensues, he opens the door, his father immediately understands, “Not you as well…”

This ambivalence of this scene is fascinating – on the one hand it functions as allegory of being caught in the act of masturbation (I made a similar parallel in my review of X-Men 2 – m k-p), on the other hand it seems to concern even more fundamentally the act of self-harm. Both noted patterns of teenage behaviour – and it seems to me that what the audience is being invited to understand here is that from a certain perspective (namely, that one of militant heteronormativism) these acts amount to the same act: sexuality (masturbation) as disease, as sin.

I couldn’t help thinking, too, of the Birthday Party’s ‘Mutiny in Heaven’ and the junkie-Cave’s delirial scream, ‘fucken wings burst out mah back (like ah was cuttin teeth!!)’. Transforming the body and mind through drugs is, needless to say, something else that parents dread teenagers are up to behind the locked bathroom door.

Observing the mutations of teen bodies through drugs and sex led recanting Marxist turned cultural conservative Leslie Fiedler to write of a ‘feminization’ of the young in his astonishingly prescient 1965 essay – which already referred to ‘post-Modernism’ and ‘post-humanist sexuality’ – ‘The New Mutants’ (the title of which lent itself to an X-Men spin off). For Fiedler, feminization initially appears as a kind of ultra-passivity, which immediately crosses over into schizophrenia; Fiedler is describing the spreading of a condition that someone like the psychotic Judge Schreber had already experienced back in the nineteenth century.

IT lookalike Rogue sporting ‘badly home-dyed tribute to Billie Piper’ hairstyle

Strafed by the rays of God, Schreber felt himself to be ‘unmanned’. His delirium – echoed in the central image of the techno-invaginated Max in Cronenberg’s Videodrome – was already telematic (but, then, isn’t schizophrenia, its best known symptom the hearing of voices, an inherently telematic disorder?) The other side of the schizophrenic dread of being overwhelmed by a signal transmitted from outside is the terror of yourself becoming the transmitter. In both states, there is what Baudrillard characterized as ‘the absolute proximity, the total instantaneity of things, the feeling of no defense, no retreat’. Not only Phoenix, but also Rogue is in horror of ‘the unclean promiscuity of everything which touches, invests and penetrates without resistance’ – precisely because she herself is the one whose touch is deadly, who can touch (and destroy) without resistance. Rogue therefore chooses subjective death – the elimination of her powers through the ‘mutant cure’ – in order to return to ‘heterosexual normativity’ via her relationship with Bobby Drake.

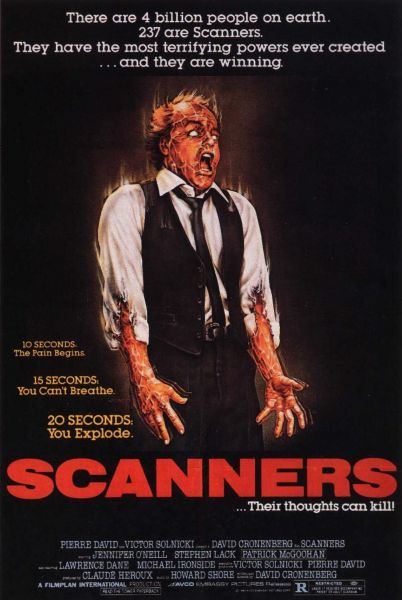

The best known film to deal with the dread of becoming a transmitter of lethal telekinetic signal is of course Cronenerg’s Scanners. (Is it any accident, by the way, that Loefah samples Scanners in his dubstep favourite, ‘Goat Stare’? Isn’t the ‘scanning experience’ an analogue for being irradiated by bass waves?) Yet Scanners was in many ways a recapitulation of De Palma’s underrated Fury, which itself refrained the theme of ‘uncontrollable telekinetic power’ in De Palma’s previous, more celebrated, effort, Carrie.

|  |

The problem, in Carrie, Fury and The Last Stand is the failure of the Father. If, as Josef K persuasively suggests, The Last Stand re-presents, in the characters of Professor X and Magneto, the splitting of the Father into the Name of the Law and Pere Jouissance, then the film is remarkable for its refusal to vindicate either model of paternal authority. Both Fathers fail in their attempts to control, help or manipulate (and the film is very clear that these terms become interchangable) Phoenix; both, that is to say, cannot heed the cry of ‘Father, can’t you see I’m burning?’ which her desire poses.

In the end, the only riposte to the unstoppable force of the Death Drive is the immovable object of love. It is tempting to read the highly affecting scene in which Wolverine kills Jean after being flayed by Phoenix’s ‘arrows of desire’ as Eros winning out over Thanatos. In fact, Wolverine’s love for Jean, as much as Phoenix’s ‘pure will, instinct, glee, rage’, is beyond the pleasure principle. Earlier, Wolverine withdraws from a sexual encounter with the newly revived Phoenix (a scene that promised to be utterly Burroughsian: reality-warping psychic vortex fucks animal-warmachine cyborg), suppressing Eros in the interests of Agape. In his discussion of this scene, Josef K refers to Zizek’s “I love you, but inexplicably I love something in you more than you, and therefore I destroy you.” Yet, doesn’t the scene present something that is almost the reverse of this? ‘Even though you are totally possessed by something in you that is more than you, I still love you, and therefore I destroy you.’