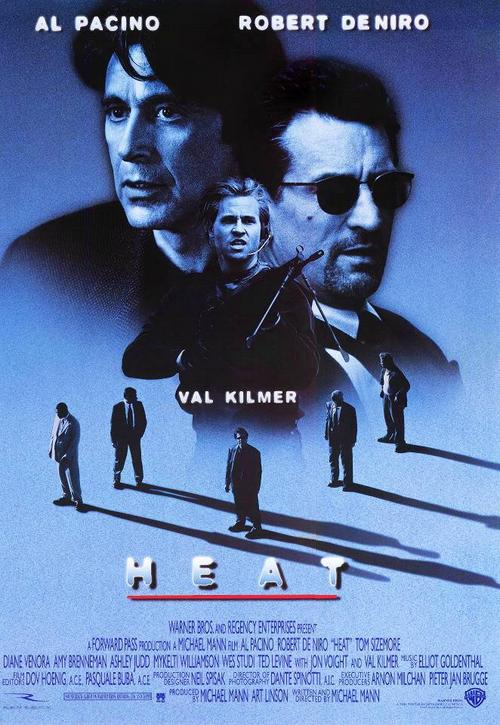

Don’t let yourself get attached to anything: post-Fordist crime in Michael Mann’s Heat

Fri. August 26, 2005Categories: Abstract Dynamics

Re-watching Michael Mann’s Heat, now a decade old.

Heat now looks not just like a great 90s film, but a great film about the 90s. There were probably none better.

This is a post-Fordist organized crime movie, in which the scores are undertaken by crews, not Families, in an LA of polished chrome and interchangable designer kitchens, of featureless freeways and late-night diners, a no-place that is very far from being a utopia. All the local colour, the cuisine aromas, the cultural idiolects which the obvious comparison pieces, the Coppola and Scorsese gangster flicks of the seventies*, depended upon, have been leeched out, painted over, re-fitted and re-modelled. You could be anywhere … It is a world without landmarks. Ours: a branded Sprawl, where markable territory has been replaced by endlessly repeating vistas of replicating franchises. The ghosts of Old Europe that stalked Scorsese and Coppola’s streets have been exorcised, buried with the ancient beefs, bad blood and burning vendettas somewhere beneath the multinational coffee shops.

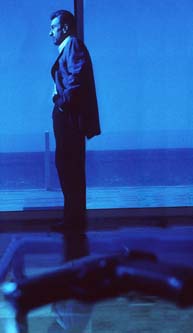

You can learn a great deal about the world the film projects from considering the name of the character De Niro plays – ‘Neil McCauley’. It is an anonymous name, a fake passport name, a name that carries no culture freight, that is bereft of history, as unrevealing as a forced smile (compare ‘Corleone’, and remember that the Godfather was named after a village). McCauley is perhaps the part that De Niro played that is closest to the actor’s own personality: a screen, a cipher, depthless, icily professional, lacking in reflexivity, stripped down to pure Method (‘I do what I do best’). When McCauley meets the love interest, Eadey, he is reading a book on metals.

McCauley is no mafia Boss, no puffed-up chief perched atop a baroque hierarchy governed by codes as solemn and mysterious as those of the Catholic Church and written in the blood of a thousand feuds. Ask his Crew if they are blood brothers, and they would laugh at you. They are professionals, hands-on entrepreneur-speculators, crime-technicians, whose credo is the exact opposite of Cosa Nostra family loyalty. Family ties are unsustainable in these conditions, as McCauley tells the Pacino character, the driven detective, Vincent Hanna. ‘Now, if you’re on me and you gotta move when I move, how do you expect to keep a… a marriage?’ Hanna is McCauley’s shadow, forced to assume his insubstiantility, his perpetual mobility. Like any group of shareholders, McCauley’s crew is held together by the prospect of future revenue; any other bonds are optional extras, almost certainly dangerous. Their arrangement is temporary, pragmatic and lateral – they know that they are interchangable machine parts, that there are no guarantees, that nothing lasts. Compared to this, the goodfellas seem like sedentary sentimentalists, trapped animals rooted in dying communities, doomed territories. McCauley and his Crew couldn’t be less interested in Territory; it is Capital they are after. As McCauley tells those in the bank during the heist, ‘We’re here for the bank’s money, not your money.’

McCauley’s creed – he says it twice – could be written in every post-Fordist boardroom. ‘A guy told me one time, “Don’t let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner.”‘ McCauley’s problem, of course, is that, when it comes to the crunch he is unable to live by this. His fate could stand as a warning to all of us, workers and managers, that late capitalism and attachment do not mix.

* Goodfellas came out in 1990, but it was already elegiac, already about a moment that had passed. Casino was actually released in the same year as Heat, and it, too, was self-consciously a period piece, a historical drama about the near-past.