Dead to the wordly

Sun. July 6, 2008Categories: Abstract Dynamics

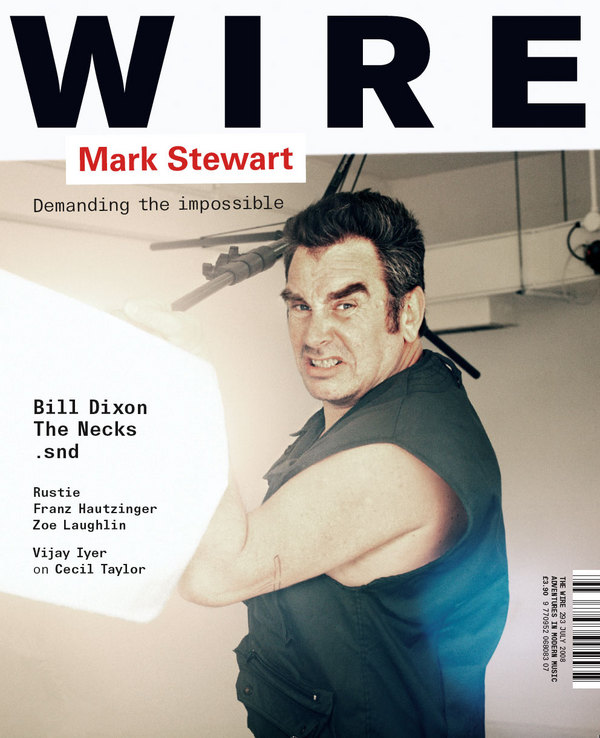

(being a belated plug for the July issue of The Wire)

“I grew up in a family where psychic stuff was normal,” Mark Stewart told me when I interviewed him for The Wire. “My grandmother was a clairvoyant and we would have sessions every Sunday when we were kids.” I didn’t end up including this in the feature, but it strikes me that one link between the post-punk trio I wrote about in the July issue (Stewart, Mark E Smith, Ian Curtis) is channeling. In order to get at what is at stake in so-called psychic phenomena (and its relationship to performance and writing), it’s necessary to chart a middle course between credulous belief in the supernatural and the tendency to relegate any such discussion to metaphor: being taken over by other voices is a real process, even if there is no spiritual substance.

The most disquieting section of the Joy Division documentary is the cassette recording of Curtis being hypnotised. It’s disturbing, in part because you suspect that it is many ways the key to Curtis’s art of performance: his capacity to evacuate his self, to “travel far and wide through many different times”. You don’t have to believe that he has been regressed into a past life in order to recognise that he is not there, that he has gone somewhere else: you can hear the absence in Curtis’s comatoned voice, stripped of familiar emotional textures. He has gone to some ur-zone where Law is written, the Land Of The Dead. Hence another take on the old ‘death of the author’ riff: the real author is the one who can break the connection with his lifeworld self, become a shell and a conduit which other voices, outside forces, can temporarily occupy.

Mark E Smith once understood this very well; perhaps still understands it, even now, sitting at the bar at the end of the universe, his psychic antenna dulled by booze. In a very different way to Curtis, Smith at his most incendiary was a depersonalised host for stray, strange signal. Where Curtis’s dispossession was concentrated into a single and singular voice that sounded as if it was already dead, Smith became a cacophony, an ‘ESP medium of discord’, a damaged transmitter that was like Baudrillard’s schizophrenic: a switching centre for all the networks of influence. That is partly why the Smith ‘auto’ ‘biography’ is so disappointing. Biography is an end of history form, deflationary and reductive in its rush to reassure us that it was always about people. The point that artists come to believe it it is all about them – and not about their ability to channel externalities which erased them – is usually the point at which they lose it.

The Joy Division documentary succeeds in a way that neither Control nor the Mark E Smith biography did not, precisely because it resists this biographical closure. It emphasises the difference – the absolute difference – between Curtis the biographical subject and Curtis the singer. Carl was right to say that, in Control, “Curtis isnt seen from anyones perspective but his own”. But ‘his own perspective’ is very far from being the subjectively destituted perspective of the music, the art. The naturalistic distance that Control adopts keeps us outside all that; with the result that the focus on Curtis makes him seem not sympathetic but self-centred, and inexplicably so. There’s very little sense of what it was that captured him, what drove him and rode him, the dread-ful euphoric trips out of his self to which he was addicted.

Voices, de-naturalised voices … Curtis, Stewart and Smith all deprive the voice of its homeliness and its worldliness. Curtis because his voice was so sepulchurally cold; Stewart because his voice is so hot, so inflammatory. Fire, speak with me … As I try to argue in the Stewart feature, Stewart remains an incendiary presence live because of his ability to channel rage and utopian longings (“one spark can start a prairie fire“), to set aside the etiquette of ‘being a person’, someone who is self-possessed, as represented in the usual expressive repertoire of a singer. The sound of the impossible being demanded as a resistance to the dreary certainties of capitalist realism.