Can it be that it was all so simple then?

Sat. November 4, 2006Categories: Abstract Dynamics

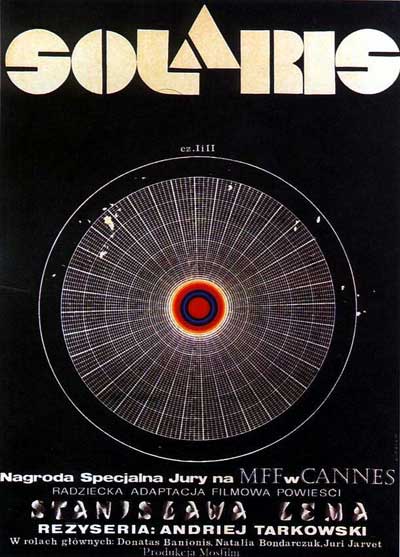

The reality of nostalgia is nowhere better invoked than at the end of Tarkovsky’s Solaris. When the camera pans away from Kelvin embracing his father on the rain-soaked steps of his dacha, we realise that the scene is yet another of the simulations produced by the inscrutable planet. The whole film can be read as a treatise on the dangers and seductions of nostalgic desire. With the perversity of literalism, the revenants that the planet throws up consist of nothing but memory, and in the grotesque absurdities of Kelvin’s relationship with his wife’s double, Solaris demonstrates that desire may well depend upon the inhuman partner, but the inhuman partner alone can only be an object of horror. (And what is this dreaming ocean – absolutely alien to us, yet horribly aware of our every desire and memory – if not the unconscious itself?)

Tarkovsky’s film ends with a simulation of a place – the Russia that Tarkovsky would soon lose, and which he would pine for in his own Nostalgia. The elision between time and space in nostalgia – as Simon tells us, nostalgia was originally defined as an intense longing for a place, before it was thought of as a craving for the past – is easy to credit. (Simon is right that the precedence of the spatial over the temporal holds even if ‘nostos’ originally meant ‘return’ rather than ‘homeland’. Interestingly, of course, ‘return’ carries both spatial and temporal connotations.)

No doubt the fantasy of time travel is so powerful because the idea that the past is waiting somewhere, pristine, intact, awaiting our return, is so hard to eradicate from the unconscious. Nostalgia reverses the sense of Hartley’s epigram whilst retaining its equation of lost time with a faraway place: the past is not a foreign country but a homeland. Here we must recall one of the most famous passages in Freud’s essay on ‘The Uncanny’:

- It often happens that neurotic men declare that they feel there is something uncanny about the female genital organs. This unheimlich place, however, is the entrance to the former Heim [home] of all human beings, to the place where each one of us lived once upon a time and in the beginning. There is a joking saying that Love is home-sickness; and whenever a man dreams of a place or a country and says to himself, while he is still dreaming: this place is familiar to me, Ive been here before, we may interpret the place as being his mothers genitals or her body. In this case too, then, the unheimlich is what was once heimisch, familiar; the prefix un [un-] is the token of repression.

What Freud calls the ‘lascivious’ fantasy of ‘intra-uterine existence’ seeks something impossible, and not only physically. The logic of desire is itself contradictory: what is sought is a conscious experience of a dissolution of the ego, the very seat of consciousness. If this is the model for all nostalgia, then it is clear that the nostalgic desire seeks something more unattainable even than the recovery of the past; it wants the past as seen from now. The past which we had to live through headlong can be savoured only now that it has been subtracted from the flow of becoming.

Thomas Hardy’s poems, topical at the moment because of Claire Tomalin’s Time-Torn Man, (a ‘haunted and haunting biography’ according to Hilary Spurling in The Observer) bring out this dimension of nostalgia with a peculiar power. ‘The Self-Unseeing’ pictures Hardy – doubled like Spider in Cronenberg’s film, an observer of the past and an actor in it – watching a bucolically re-staged scene from long ago: ‘Childlike, I danced in a dream;/ Blessings emblazoned that day/ Everything glowed with a gleam; Yet we were looking away!’ And yet it is clear that the ‘gleam’ depends upon the ‘looking away’; it is something that the scene has acquired by virtue of a long period of time having elapsed. What is mourned for is an unselfconscious casualness; what is wanted is the possibility of experiencing those moments again, but with the added piquancy brought by age and loss. Again, this is not only empirically impossible; to re-experience the past like this would be to lose the very lightness that is yearned for in it.

In his later years, Hardy retreated from the modern world his novels had confronted (a world that, in many ways, he saw as not modern enough; Jude, for instance, was destroyed by the dead man’s grip of a past) and gave himself over to composing a lyric poetry decorated with archaic diction. All of Hardy’s love poems – written by an old man, recalling feelings he had experienced half a century before – combine nostalgia with necromancy. But the figure they are devoted to was in large part his own invention. The poems are seances that summon an inhuman partner, a fantasmatic double of his dead wife. When she was alive, Hardy’s wife Emma suspected that he could only love imaginary women (she believed that he was in love with his own creation, Tess). It is ironic then that the love poetry Hardy addressed to her confirms that he could only love his own creations, since it was only when Emma herself had died and could become an imaginary woman, a ‘voiceless ghost’ as he put it in ‘After a Journey’, that Hardy could love her again. (Emma and Hardy had been effectively estranged for many ears.) ‘After a Journey’ makes repeated play of the doubleness of the word ‘haunt’, entangling a sense of the place with the call of the past in a way that is typical of all Hardy’s love lyrics, which are such vivid illustrations of the nostalgic impulse in general.

What Hardy’s poems shy away from is the possibility that the much longed-for past is a retrospective confabulation; that his love for Emma thrived on obstacles, and gained its impetus at the end from the most serious obstacle of all, death.

Can it be that it was all so simple then?

By contrast, the reason that ‘The Way We Were’ is one of the best nostalgia songs is that it is precisely about the ways in which nostalgia depends upon a falsification – a ‘misty watercolouring’ – of the past. When the Wu Tang Clan sampled ‘The Way We Were’, the line they hijacked and looped – from the Gladys Knight version, not the Streisand original – was ‘can it be that it was all so simple then?’, the plaintive tremor of the original now become a repeated reproach, its wraith-like insubstantiality made all the more affecting by being placed in RZA’s siren-scarred brutalist NYC.

In the original, of course, this line is followed by, ‘or has time rewritten every line’? The impossible existential dilemma – ‘and if we had the chance to do it again/ would we?’ – poses a Nietzschean challenge (one reminscent of the plight of the lovers in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind), which Hamlisch’s lyrics resolve in an appropriately Nietzschean way, with an celebration of the power of forgetting (falsification as the necessary precondition for all affirmation): ‘what’s too painful to remember, we simply choose to forget’. We choose to forget… rather than we are unable to remember, as in trauma. We return to a past, the past does not return to (or through) us; the repetition is not a compulsion.

It strikes me, however, that the nostalgia mode is another kind of pathology altogether. The Way we Were was part of the 1970s’ thematization of nostalgia, as were Roxy, whose dyschronic collages might have seemed quintessentially postmodern twenty years ago, but which now look like exercises in modernist nostalgia (with Bowlly, rock and roll and a – then still imaginable – synthetic future converging in an impossible Overlook Hotel simultaneity).

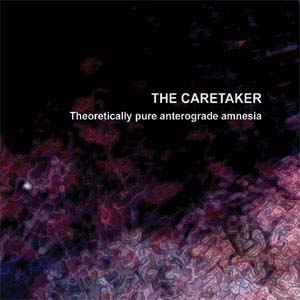

Mention of the Overlook inevitably brings to mind is the Caretaker who, with Theoretically pure anterograde amnesia has provided one of the most acute – and also, not coincidentally, one of the bleakest – diagnoses of our condition. As I put it in my sleevenotes, Theoretically pure anterograde amnesia is not about a craving for the past but inability to get out of the past. It might seem strange to suggest that our condition is amnesiac, but anterograde amnesia is the incapacity to produce new memories. Beneath the superficial bonomie of the endless television rundowns (100 bests, I Love 1971-2-3-4……), Theoretically pure anterograde amnesia finds a dementia. The young have become like the very old, living in a past that they confuse with the present. More horrible than being trapped in one’s own reminiscences, this is about being condemned to forever wander someone else’s memory lanes (a fate which cannot but remind us of Rachel’s situation in Blade Runner). The present looms emptily, an unsymbolizable abstraction, an abandoned echo chamber, forbidding in its abstraction; the only landmarks are the fragments of the past which flare intermittently in the murk. The genius of Theoretically pure anterograde amnesia is that it reinforces the very condition it describes; the seventy odd tracks, each one Beckett-sparse, are impossible to remember – each time you hear them, it is as if for the first time (even though the first time was already an instance of deja entendu).