Built to Last

Tue. July 31, 2007Categories: Abstract Dynamics

To the splendid opulence of Eltham Palace on Sunday, one of London’s hidden jewels recently eulogised by Owen. Like Portmeirion, but in a very different way, the architectural palimpsest of Eltham Palace – ‘a 1930s graft onto a 15th century Tudor pile’ – is an example of sympathetic modernization. The ‘deco rotunda’, the ‘rooms done in whichever historicist style currently favoured, in this case some ersatz Dutch and Italian bedrooms (with the telephones and radio speakers secreted in imaginative places)’, were ostentatiously new – as Owen observes, ‘the sinister ambience of the moderne’ is everywhere in Eltham Palace – without being violent desecrations.

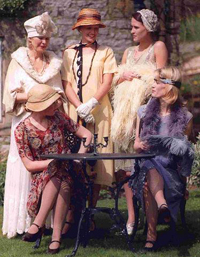

By happy accident, our visit coincided with a show of Thirties fashion organised by the gloriously-named Notty Hornblower of Hope House Costume Museum and Restoration Workshop. Hornblower’s obvious love and enthusiasm for the clothes set her far apart from the tight-lipped smugonautics of the typical – shudder -‘curator’. Her restorations of the dresses, coats and nightwear amounted to acts of reverential hauntological summoning. Her intimate knowledge, not only of the fine details of the clothes themselves, but also of their owners and their personal histories, brought a whole era of women’s lives and preoccupations back to unlife. Naturally, not all of the owners were known, since many of the clothes had been rescued from charity shops, jumble sales or other anonymous sources. She discovered one especially stunning dress, whose detail was all in the sleeves, unceremoniously stashed in a box of oddments, the deco sleeve drape over the side, almost as if it were beckoning to her, the dress quietly inviting its own reconstruction. In the cases where the owner is not known, there is only speculation, spectrality…

- In another apartment, not far away, in Kensington, he opened a wardrobe and found half a dozen pure silk Fortuny dresses that must have formerly been worth a few thousand pounds. They were not hung, but twisted and rolled into skeins to preserve their pleats. These were said to be so fine that one could pass them through a wedding ring, and as he lifted them, he marvelled at their lightness and the soft shining of their subtle colours in the dusty illumination from the windows.

In this same apartment he came across photographs of the woman who must have worn these dresses as a young girl. She was very slender and typically thirties in style – short hair, pale face, dark eyes and lips. The photos showed her standing among her friends in the gardens and drawing rooms of the well-to-do through the years of changing fashions – the austerity of the forties, the grey fifties, and as a good-looking mature woman in the early sixties. After that there were no more photographs, though she must have lived in this apartment for long afterwards.

- John Foxx, ‘The Quiet Man‘

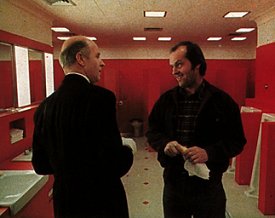

To see these clothes amidst the faux-Hollywood finery of Eltham palace, with elegant thirties tearoom pop wafting in the background, was to experience a double nostalgia, a nostalgia for modernism that had already been reflexively worked through in the 70s, in Roxy, Pennies from Heaven and The Shining. Walking around the long-vacated apartments of the Cortaulds, you half expect to come upon an ‘obsequious manservant’ of the Delbert Grady type, a relic of a disappeared social hierarchy, a ghost who doesn’t remember that he is dead (‘it’s all forgotten now…’) , delivering drinks to deceased masters who will never receive them. Yet Eltham palace is rich in its own wealthy ghosts and, as so often in English Heritage sites*, you imagine the kind of British film that it is impossible to conceive of being made now: a lavish existential epic anatomizing the heartaches within all those leisure class dreamhomes… (Eltham Palace was actually used in the TV adaptation of Brideshead Revisited but, as Owen when we talked after my visit on Sunday, surely Eltham Palace deserves better than that…)

|

Jameson’s comments on the nostalgia of The Shining are worth recalling here, since they are highly pertinent to current discussions of class envy:

- The nostalgia of The Shining, the longing for collectivity, takes the peculiar form of an obsession with the last period in which class consciousness is out in the open: even the motif of the manservant or valet expresses the desire for a vanished social heirarchy, which can no longer be gratified in the spurious multinational atmosphere in which Jack Nicholson is hired for a mere odd job by faceless organization men. This is clearly a “return of the repressed” with a vengeance: a Utopian impulse which scarcely lends itself to the usual complacent and edifying celebration, which finds its expression in the very snobbery and class consciousness we naively supposed it to threaten.

In retrospect, The Shining, rather like Pennies from Heaven and the early Roxy, can be seen not as an example of postmodernism, but rather as a case of pulp modernism. It was still an interrogation of the pull of nostalgia rather than an exemplification of the nostalgia mode; it was still awake, even if its eyes were growing heavy-lidded; still in history, not yet given over to the nightmare of the end of history from which we are yet to awake. Deliberate anachronism means that, for all its soft focus sweet sickness, The Shining‘s longing for the past never produces a seamless simulation. The Shining‘s Gold Room is ostensibly set in the Twenties, but is soundtracked by music from the Thirties – by Ray Noble and Al Bowlly, who feature so heavily in Potter’s work, as it happens. And here is the dishevelled Jack, Oedipus at the end of History, dreamer dreamt by Old dreams, dreaming of Good Old Days where a man knew his place; here he is, a dressed-down mess, drink spilled down his oh-so-inappropriate lumberjacket. He does not fit in – sartorially, existentially, temperamentally. He’s not the right sort of chap at all…

Unmask! Unmask!

In the popular modernism of those thirties fashions, we see an embellishment, a beautification, of the everyday. But at the end of History we all look like Jack, a.k.a. the Last Man, a.k.a. Oedipus, the avatar of capitalist realism. (Capitalist realism, the myth of no myths, is the dullest of masques, where Capital calls the tune, and the revellers imagine that they are their faces.) Life is not even a dress rehearsal now. We tramp around in track suits through the artfully arranged relics of previous events, beliefs and rituals, forever the consumer, the spectator, of (past) stability … ours is world that’s constantly changing. (So this is the atermath…)

Many of the clothes in Lotty Hornblower’s thirties collection, she said proudly, are still in immaculate condition after 70 years. (Amazing, isn’t it, how they managed to produce commodities of such durability without Quality managers, mission statements and ‘core values’?) It was a period of capitalism still naive enough to build things to last… by contrast with the inbuilt obsolescence of the OedIPod at the end of history, where nothing lasts, and only trash keeps returning…

* I fantasise about a collaboration with English Heritage called English Hauntology, in which the sites are used for some Weird confection of fiction, film and music …