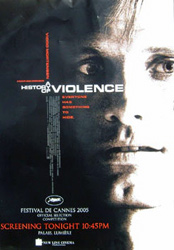

A seamless tissue of fantasies

Tue. October 18, 2005Categories: Abstract Dynamics

Jodi Dean has an interesting reading of A History of Violence that is contrary to mine. She interprets the film as ‘the son’s fantasy of violence underlying the passive, ordinary goodness of his father’. (The son, as Jodi rightly says, was entirely absent from my account of the film). For Jodi, the film is a coming-of-age drama of an aberrant kind, in which, only by splitting ‘the father into the good father of the symbolic and the obscene father of the mob, of underworld violence’ can ‘the son … grapple with his own dilemmas of becoming a man.’

Ingenious as this reading is, I find it unsatisfactory for a number of reasons. First of all, A History of Violenc frustrates an ‘epistemological’ interpretation of this type at every turn. It is not a film like Fight Club, Memento and The Machinist, i.e. an enigma which resolves into questions of epistemological motivation. In those films, once we realise that what we have seen is the product of a psychiatrically and/or neurologically disordered mind, everything falls into place. They are jigsaw puzzles which can be put together, and Sense can be restored. A History of Violence, by contrast, is closer to Mulholland Drive and Eyes Wide Shut, films which scramble Sense and leave it scrambled. Appearances to the contrary, there is no moment of ultimate revelation in A History of Violence. The revelation at the level of diegesis – our discovery that Tom is Joey – does nothing to resolve the film’s most troubling quandary, which is ontological rather than epistemological. At the end, nothing makes sense, because the questions the film has raised – not only ‘what here is real?’, but, more profoundly, ‘what is (the) Real’? – have not been settled.

Part of the problem with Jodi’s reading is that there is no clear ontological hierarchy in A History of Violence. Nothing is ‘marked’ as more real than anything else. This, again, is by contrast with Fight Club or The Machinist, which turn upon a discrepancy – concealed in the early parts of the films, but exposed by their end – between the psychotic delirium of the lead characters and a publicly-validated empirical reality. But there is no such discrepancy in A History of Violence, largely because there is no uncontested, convincing, empirical reality from which we can clearly differentiate the fantasmatic elements; there is only a seamless tissue of fantasies.

This is what makes the superficially conventional A History of Violence more ontologically unsettling than something like Existenz. Existenz presents a ’embedded’ ontological hierarchy, in which different realities are contained within each other, the ‘most real’ being the one that embeds the rest. By the end of Existenz, this hierarchy has been disrupted, first, by the ‘reality bleed’ between ontological levels, so that supposedly ‘inferior’ realities come to contaminate ‘superior’, higher-level realities, and second, by the suggestion of an infinite regress of realities, with no ground level. A History of Violence gets to this sense of groundlessness or ‘abgrund’ without recourse to a ‘vertical’ model of nested realities. Realities are not placed one inside the other, but juxtaposed, one next to the other. A different kind of ‘reality bleed’ altogether.

As Jodi rightly observes, ‘When we first see [the son] he is part of a completely fantastic image of the perfect family: the teenage son concerned about his little sister’s bad dream.’ This, then, would appear not to be ‘real’. But what is? There is barely one situation in which the son finds himself that is not equally implausible: his verbal and then physical besting of the bully, like his shooting of the gangster to save his father’s life, seem ‘obviously’ fantasmatic. But, then, so does everything else in the film. Jodi might argue that the film’s ‘real Real’ is what is not depicted at the level of its diegesis – yet, her reading, of necessity, relies on privileging certain elements of what we DO see (most obviously, we have to accept that the son really is a son, really is at high school etc etc).

Jodi’s reading also surreptitiously resolves the film’s ontological tension, by assuming that the ‘Joey reality’ is ontologically inferior to the ‘Tom reality’. On what grounds, though? As Jodi herself notes, the Stall domestic Paradiso is no more ‘real'(istic) than the organized crime Inferno; it is just that, in the first case, the fantasies derive from melodrama, while in the second, they are taken from the gangster genre. (In this respect, A History of Violence can be compared with The Shining, which similarly mediates between the conventions of family drama and those of another genre, in that case, Horror. See Walter Metz’s intertextual analysis here.) Paradoxically, the Stall family only seems realistic once it is menaced by mobsters who are no more realistic. If there is ‘realism’ at all, it is generated by the tensions between the conventions of two genres.

Jodi says that my reading was too quick to remove fantasy. But I would want to argue that Jodi, like Graham Fuller in Sight and Sound, contains fantasy by giving it a diegetic motivation. What this leaves out is in a way the most obvious fantasmatic level: that of our own fantasies. It is not that the events of the film can be reduced to the fantasy of one of the characters; no, the film forces us to confront the way in which the characters are OUR fantasies, the violence is the violence of OUR wish fulfillments.

Which is why I wholeheartedly concur with Jonathan Rosenbaum (via).

‘There’s hardly a shot, setting, character, line of dialogue, or piece of action in A History of Violence that can’t be seen as some sort of cliche,’ he writes. ‘Its fantasies about how American small towns are paradise and big cities are hell are genre standbys that Cronenberg milks at every turn. But none of this plays like cliche; Cronenberg is such an uncommon master of tone that we’re in a state of denial about our familiarity with the material — a kind of willed innocence that resembles Tom Stall’s own disavowals.’