SHE’S NOT MY MOTHER

Thu. June 10, 2004Categories: Abstract Dynamics

Cronenberg’s Spider – warning: contains spoilers

Interviewer: It’s hard to see this movie and not consider that all our memories are creations.

Cronenberg: But they are, they totally are.

Joy Division: Watch from the wings as the scenes were replaying

We saw ourselves now as we never had seen

Cronenbergs Spider – adapted from Patrick McGraths superb novel is a study of schizophrenia that couldnt be further removed from the clichéd image of madness in cinema. There are numerous examples of this, but the one that comes immediately to mind (perhaps because I watched it recently) is Windom Earl in the second season of Twin Peaks: gibbering, histrionic, megalomaniac. Think also of Nicholsons Joker in the first Batman movie. Madness is here imaged as a kind of absurdly inflated ego; a self that knows no bounds, which wants to expand itself infinitely. As played by Ralph Fiennes in Cronenbergs film, Spider, too, has a precarious sense of his own limits, but, far from wanting to spread further into the world, he seems to want to make himself disappear. Everything about him his mumbling speech, shambling movements and – screams withdrawal, retreat, terror of the outside. Thats because, as ever in Cronenbergs schizoverse, the outside is already inside. And the reverse.

McGraths novel is set entirely within the head of its archetypal unreliable narrator, Spider, since it is written as a series of diary entries. To simulate this, Cronenberg could have gone with the strategy employed in the early versions of the script and used voiceover (although anyone whos seen Spike Jonzes Adaptation will remember Robert Mckees rant about that particular technique). In the end, Cronenberg strips out Spiders narrative voice altogether, with the result that the film is, in a strange way, truer to the novel than the novel itself. In the novel, Spiders articulacy gives him a kind of self-awareness and (albeit limited) transcendence of his mania. In the film, there is no distance, no narrative voice, only a ceaselessly productive narrative machine, chattering out multiple permutations. In place of the transcendent offscreen voice, we are presented with Spider as a character in his own delirium, the adult version of himself observing and writing, always writing, as the memories of his childhood life play out. As Cronenberg has observed, it is almost as if Spider is directing his own memories. One journalist said to me, “When we see Spider in his own memories, peeking in the windows or hiding in the corner, isn’t that like a director being on the set?” I hadn’t thought of it that way, but he is redirecting and rechoreographing his memories. We are reminded that the dreamer is every character in his dream.

So Spider develops a naturalistic expressionism, or expressionist naturalism. Its strangely solitary London is, Cronenberg says, an expressionist London. Spider captures the boiled potatoes atmosphere of the pre-rock n roll Fifties, its muted colours as washed out as cabbage water.

The film of Cronenbergs which Spider most resembles is Naked Lunch; not only because it, too, is based upon a supposedly unadaptable book, but also because both films principally concern writing, insanity, masculinity and the death of a woman. In both Naked Lunch and Spider, the phantasmatically reiterated murder of a woman is the pivotal event, the lacuna around which the films circle. In Naked Lunch, Lee initially disavows the killing of his wife Joan by attributing it to the influence of Control. Lee is only able to accept minimal responsibility for the killing when he is required, at the end of the film, to assassinate Joan, or at least her double, again. The re-staging of the death is less an admission of ethical responsibility than an attempt to own it, to make sense of it. Such is the logic of trauma. (Reminding us of Ballards description of the motives of the schizo in The Atrocity Exhibition: He wanted to kill Kennedy again, but this time in a way that made sense.)

In Spider we are initially led to believe that Spiders father, Bill Cleg (Horace in the novel) has killed Spiders mother after embarking on an affair with the fat tart Yvonne (Hilda in the novel). No sooner has Bill brutally and casually murdered his wife, rolling her into a hastily dug grave in the earth of his allotment (out with the old, Yvonne callously cackles), than he moves Yvonne into his home. At this point, our suspicions that something is amiss with Spiders narration begins to harden into a conviction. But its only at the end of the film that we learn what appears to have really happened: it is Spider himself who killed his mother, gassing her whilst apparently suffering from a delusion that she is another person. The early exchanges between Spider and his father take on a different significance (Spider: Shes not my mother. Bill: Well, who is she then?) The final scene sees Bill rescuing Spider from the house, and desperately trying to revive Yvonne, who in death, has become, once again, the dark-haired Mrs Cleg.

While this seems to be the preferred interpretation, the film does not close down any of the narrative possibilities it has opened up . I think we can enumerate nine distinct narrative options that the film leaves open:

Rather than resolving the ambiguities of McGraths novel, the film actually amplifies them. In the novel, we at least learn (it seems) that Spider has been incarcerated for killing his mother (even though he continues to maintain that it was his father who was responsible for the death). In the film, the twenty years between Mrs Clegs death and Spiders arrival at the halfway house are a blank. We know, or think we know, by inference, that he has been in a psychiatric institution, but no more.

Miranda Richardsons performance is crucial to the maintenance of the films polysemous ambiguity. She is superb in three different roles: as the virtuous brunette Mrs Cleg, the licentious blonde Yvonne and also as the suddenly and inappropriately sexually aggressive landlady of the halfway house, Mrs Wilkinson. The situation is complicated by the fact that Yvonne is played at first by another actress altogether (at least, I think that is the case; it is a tribute to the films queasy delirium and to Richardons performance, that Im just not sure), just as Mrs Wilkinson is played for most of the film by Lynne Redgrave.

As in Naked Lunch, writing is both passive and active. Like Bill Lee, Spider, scratching away in his notebook in his idiolectic hieroglyphics, seems at one level only to be recording signal from outside; at another level, he is the producer of the whole scene, its delirealiser.

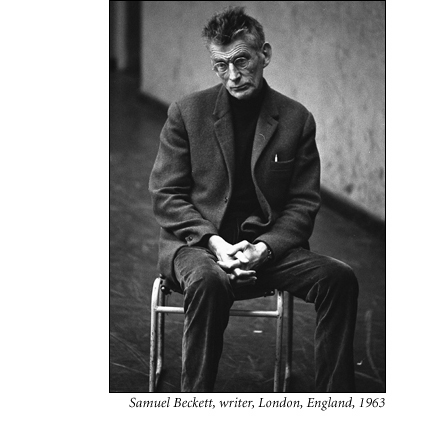

Talking about the film, Cronenberg has referred to Nabokovs theory of memory and art as attempts to recover the unrecoverable. But the figure that dominates the film is another writer who, like Nabokov, Brian McHale has referred to as a limit-modernist, Samuel Beckett. Cronenberg has said that Spiders look, with its shock of spiky hair, was very much influenced by photographs of Beckett, but the affinity with Beckett goes much deeper. Like Molloy or Malone, Spider is continually fumbling in his pockets for talismanic objects. Such partial objects mark the routes on their intensive voyages. Like McGrath, Cronenberg seduces us into identification with Spider (Cronenberg: ‘I am Spider’), taking us with him on his schizo-stroll, then strands us in the delirium…

Thought-provoking post as usual. Took me back to my reaction to the film having LOVED the novel.

Yep, Cronenberg filmed the ‘unfilmable’ book…I remember wondering why. I think he failed to the extent that he doesn’t, actually, add anything to the novel. Perhaps I don’t mean ‘add’. What I mean is: the novel exists, is wonderful, amazing and I just don’t know what the film is FOR. I think almost everything you claim for the Cronenberg here is already in the novel.

While you’re right about the ‘boiled potatoes’ atmosphere, I was nonplussed by the way the look of the film never broke with a familiar even hollywood ‘sheen’. A dank sheen to be sure, but a strangely tidy, coherent ‘look’ which I felt at odds – and not productively – with the troubled, troubling matter of the book.

On Miranda Richardson, well I just couldn’t get past her hysterical, gurning performance. ‘Come to fix my pipes, plumber?’ became a catchphrase round our house for a bit. I know she’s much admired: I just can’t abide her.

Keep ’em coming, Mark.

Surely the ‘gurning’ definitely fitted with the character as described in the novel? Partly because Hilda/ Yvonne is so hyperbolically phantasmatic? I adore MR (as you can probably tell).

I sort of agree abt the dank sheen; though I think that’s partly what makes it an expressionist, rather than a straightforward, naturalism. Otherwise, it would have just been like any other Britflick…

I think it does add to what’s in the novel. In many ways, Spider is Cronenberg’s most cinematic film, it does things that can only be done in cinema. I think precisely the avoidance of the narrative voice makes it incredibly different from the novel: stunningly, in the film, we simultaneously see only from Spider’s perspective (without ever hearing him) and also see Spider as others see him…