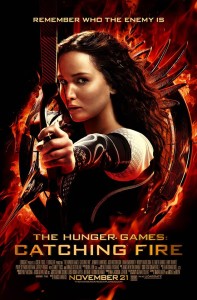

Remember Who The Enemy Is

Mon. November 25, 2013Categories: Abstract Dynamics

There’s something so uncannily timely about The Hunger Games: Catching Fire that it’s almost disturbing. In the UK over the past few weeks, there’s been a palpable sense that the dominant reality system is juddering, that things are starting to give. There’s an awakening from hedonic depressive slumber, and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire is not merely in tune with that, it’s amplifying it. Explosion in the heart of the commodity? Yes, and fire causes more fire …

I over-use the word ‘delirium’, but watching Catching Fire last week was a genuinely delirious experience. More than once I thought: How can I be watching this? How can this be allowed? One of the services Suzanne Collins has performed is to reveal the poverty, narrowness, and decadence of the ‘freedoms’ we enjoy in late, late capitalism. The mode of capture is hedonic conservatism. You can comment on anything (and your tweets may even be read out on TV), you can watch as much pornography as you like, but your ability to control your own life is minimal. Capital has insinuated itself everywhere, into our pleasures and our dreams as much as our work. You are kept hooked first with media circuses, then, if they fail, they send in the stormtrooper cops. The TV feed cuts out just before the cops start shooting.

Ideology is a story more than it is a set of ideas, and Suzanne Collins deserves immense credit for producing what is nothing less than a counter-narrative to capitalist realism. Many of the 21st century’s analyses of late capitalist capture – The Wire, The Thick Of It, Capitalist Realism itself – are in danger of offering a bad immanence, a realism about capitalist realism that can engender only a paralysing sense of the system’s total closure. Collins gives us a way out, and someone to identify with/as – the revolutionary warrior-woman, Katniss.

Sell the kids for food

The scale of the success of the mythos is integral to its importance. Young Adult Dystopia is not so much a literary genre as a way of life for the generations cast adrift and sold out after 2008. Capital – now using nihiliberal rather than neoliberal modes of governance – doesn’t have any solution except to load the young with debt and precarity. The rosy promises of neoliberalism are gone, but capitalist realism continues: there’s no alternative, sorry. We had it but you can’t, and that’s just how things are, OK? The primary audience for Collins’ novels was teenage and female, and instead of feeding them more boarding school Fantasy or Vampiary romance, Collins has been – quietly but in plain sight – training them to be revolutionaries.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the Hunger Games is the way it simply presupposes that revolution is necessary. The problems are logistical, not ethical, and the issue is simply how and when revolution can be made to happen, not if it should happen at all. Remember who the enemy is – a message, a hailing, an ethical demand that calls out through the screen to us …. that calls out to a collectivity that can only be built through class consciousness …. (And what has Collins achieved here if not an intersectional analysis and decoding of the way that class, gender, race and colonial power work together – not in the pious academic register of the Vampires’ Castle, but in the mythographic core of popular culture – functioning not as a delibidinizing demand for more thinking, more guilt, but as an inciting call to build new collectivities.)

There’s a punk immanence about Catching Fire which I haven’t seen in any cultural product for a long time – a contagious self-reflexivity that bleeds out from the film and corrodes the commodity culture that frames it. Adverts for the movie seem like they belong in the movie, and, rather than a case of empty self-referentiality, this has the effect of decoding dominant social reality. Suddenly, the dreary gloss of capital’s promotional cyber-blitz becomes de-naturalised. If the movie calls out to us through the screen, we also pass over into its world, which turns out to be ours, seen clearer now some distracting scenery is removed. Here it is: a neo-Roman cybergothic barbarism, with lurid cosmetics and costumery for the rich, hard labour for the poor. The poor get just enough high-tech to make sure that they are always connected to the Capitol’s propaganda feed. Reality TV as a form of social control – a distraction and a subjugatory spectacle that naturalises competition and forces the subordinate class fight it out to the death for the delectation of the ruling class. Sound familiar?

Part of the sophistication and pertinence of Collins’ vision, though, is its awareness of the ambivalent role of mass media. Katniss is a totem not because she takes direct action against the Capitol – what form would that take, in these conditions? – but because her place in the media allows her to function as a means of connecting otherwise atomised populations. Her role is symbolic, but – since the capture system is itself symbolic in the first instance – this is what makes her such a catalyst. The girl on fire … and fire spreads fire … Her arrows must ultimately be aimed at the reality system, not at human individuals, all of whom are replaceable.

The removal of capitalist cyberspace from Collins’s world clears away the distracting machinery of Web 2.0 (participation as an extension of spectacle into something more pervasive, total, rather than as its antidote) and shows how TV, or, better, what Alex Williams has called ‘the Universal Tabloid’, is still productive of what counts as reality. (For all the horizontalist rhetoric about Web 2.0, just look at what typically trends on Twitter: TV programmes.) There’s a role as hero or villain – or maybe a story about how we’ve gone from hero to villain – prepared for all of us in the Universal Tabloid. The scenes in which Plutarch Heavensbee gives a businesslike description of the carrot and stick nature of the Capitol’s media-authoritarian power have a withering, mordant precision. “More beatings, what will her wedding be like, executions, wedding cake …”

As Unemployed Negativity wrote of the first film: “It is not enough that the participants kill each other, but in doing so they must provide a compelling persona and narrative. Doing so guarantees them good standing in their odds and means that they will be provided with assistance by those who are betting on their victory. Before they enter the arena they are given makeovers and are interviewed like contenders on American Idol. Gaining the support of the audience is a matter of life in death.” This is what keeps the Tributes sticking to their reality TV-defined meat puppet role. The only alternative is death.

But what if you choose death? This is the crux of the first film, and I turned to Bifo when I tried to write about it. “Suicide is the decisive political act of our times”, Bifo wrote in Precarious Rhapsody: Semiocapitalism and the Pathologies of the Post-alpha Generation. (London: Minor Compositions, 2009, p55) Katniss and Peeta’s threat of suicide is the only possible act of insubordination in the Hunger Games. And this is insubordination, NOT resistance. As the two most acute analysts of Control society, Burroughs and Foucault, both recognised, resistance is not a challenge to power; it is, on the contrary, that which power needs. No power without something to resist it. No power without a living being as its subject. When they kill us, they can no longer see us subjugated. A being reduced to whimpering – this is the limits of power. Beyond that lies death. So only if you act as if you are dead can you be free. This is Katniss’s decisive step into becoming a revolutionary, and in choosing death, she wins back her life – or the possibility of a life no longer lived as a slave-subordinate, but as a free individual.

The emotional dimensions of all this are by no means ancillary, because Collins – and the films follow her novels very closely in most respects – understands how Control society operates through affective parasitism and emotional bondage. Katniss enters into the Hunger Games to save her sister, and fear for her family keeps her in line. Part of what makes the novels and the films so powerful is the way they move beyond the consentimental affective regime imposed by reality TV, lachrymose advertising and soap operas. The greatness of Jennifer Lawrence’s performances as Katniss consist in part in her capacity to touch on feelings – rage, horror, grim resolve – that have a political, rather than a privatised, register.

The personal is political because there is no personal.

There is no private realm to retreat into.

Haymitch tells Katniss and Peeta that they will never get off the train – meaning that the reality TV parts they are required to play will continue until their deaths. It’s all an act, but there’s no offstage.

There are no woods to run into where the Capitol won’t follow. If you escape, they can always get your family.

There are no temporary autonomous zones that they won’t shut down. It’s just a matter of time.

Everyone wants to be Katniss, except Katniss herself.

Bring me my bow, of burning gold

The only thing she can do – when the time is right – is take aim at the reality system.

Then you watch the artificial sky fall

Then you wake up

And

This is the revolution ….