NO NOW

Thu. February 26, 2004Categories: Abstract Dynamics

Ccru: The 7+2 Syzygy is carried by the demon Oddubb, whose associations with hyperstitious doublings reinforces its twin character.

Fascinating piece here on Pop, Jazz, time and honesty. Phil distinguishes two distinct sensibilities and temporalities: a ‘Jazz’ aesthetic, based upon the faithful reproduction of live performance and a ‘Pop aesthetic’, based around an ‘eternal Now.’ The Jazz aesthetic is exercised by profound anxieties about fidelity, about ‘honesty.’ No such worries with Pop.

Couldn’t we reverse this relation? Pop’s indifference to playing live, its dependence upon overdubs and its predilection for generating sounds that could only ever exist in the studio, means that, at the point of production, there is never a Pop ‘Now’. Sure, at the point of consumption, Pop is associated with particular moments (Phil’s point about the Now! compilations demonstrates this beautifully.) By contrast, Jazz is about a (re)captured Now, about the drama of a performance unfolding in front of us, in real time.

Phil positions Miles’ and Teo Macero’s ‘recordings’ of the late 1960s and 1970s as a diagonal between the Jazz and Pop sensibilities. They ‘seemed to explicitly deny the existence of any now, at least as far as the recording process was concerned. He argued, through his work, that studio albums had no obligation to replicate real eventsthat they could be elaborate constructs, faithful only to their own internal logic.’ The obvious genius of Miles and Macero notwithstanding, there’s a case for saying that their techniques were not so much groundbreaking as Jazz playing catch-up with Pop – a trading of Jazz’s Now for Pop’s unlife.

Phil characterises Miles and Macero’s stance as being opposed to any ‘honesty.’ I wonder if duplicity isn’t a better term than ‘dishonesty.’ Duplicity, as opposed to fidelity; duplicity, with its (lexical and semantic) connections to doubling, dubbing. The version is not a dishonest reproduction of the truth: it articulates a different ontology, in which there is no present, no presence, no originary unity, but only a time that is always (at least) doubled.

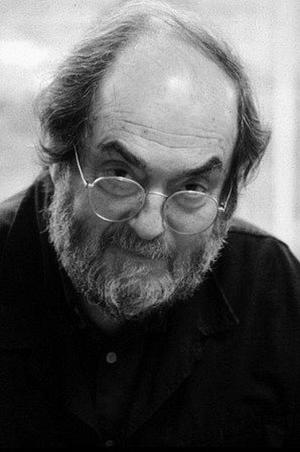

The emphasis on editing, not as a matter of ‘tidying-up’, anterior to the real process of production, but as the essential creative act, recalls Stanley Kubrick’s claim that the most crucial aspect of film directing happens in the editing suite. The opposition between film and theatre doubles the relation between Pop and Jazz. Kubrick’s notorious, seemingly sadistic, tendency to make actors repeat takes ad nauseam didn’t arise from perfectionism. On the contrary, in many ways, since, when he was watching the actors perform, Kubrick didn’t know what he wanted. The real creative process happened long after the actors, the ‘liveware’, had departed; Kubrick didn’t want to pre-empt any decisions he would make then, wanted to keep open as many options as possible. What Kubrick demanded from actors was not a unitary performance that could be faithfully reproduced on celluloid, but a pallet of potentials from which he could construct the onscreen ‘performance’, after the fact, in the editing suite. Kubrick’s anti-humanist methodology treated actors much in the way that Macero treated sounds, as manipulable traces.