London after the rave

Fri. April 14, 2006Categories: Abstract Dynamics

‘From the moment that human beings started communicating with electrical and electromagnetic signals, the ether has been a spooky place. Four years after Samuel Morse strung up his first telegraph wire in 1844, two young girls in upstate New York kick-started Spiritualism, a massively popular occult religion which attempted to fuse science and seance. […]

Now, you may think that this ghoulish dial-tweaking has gone the way of the dousing rod, but electromagnetic spiritualism is alive and well […]. Today aficionados call it Electronic Voice Phenomena, or EVP. […]

Interestingly, one of the most important requirements for good EVP is the presence of noise: a distorted channel, interference, echo, superimposition. In other words, all the active elements of our current hip-hop/dub mixology are designed to receive these spectral messages. No wonder the stuff can put you into another world.’

– Erik Davis, Dead Machines: A review of The Ghost Orchid and electromagnetic voice phenomena

A MASSIVE new addition to the sonic hauntology canon: the self-titled album by Burial on Kode 9’s Hyperdub label.

Burial is the kind of album I’ve dreamt of for years; literally. It is oneiric dance music, a collection of the ‘dreamed songs’ Ian Penman imagined in his epochal piece on Tricky’s Maxinquaye. Maxinquaye would be a reference point here, as would Pole – like both these artists, Burial conjures audio-spectres out of crackle, foregrounding rather than repressing sound’s accidental materialities. Tricky and Pole’s ‘cracklology’ was a further development of dub’s materialist sorcery in which ‘the seam of its recording was turned inside out for us to hear and exult in; when we had been used to the “re” of recording being repressed, recessed, as though it really were just a re-presentation of something that already existed in its own right’ (Penman). But rather than the hydroponic heat of Tricky’s Bristol or the dank caverns of Pole’s Berlin, Burial’s sound evokes what the press release calls a ‘near future South London underwater. You can never tell if the crackle is the burning static off pirate radio, or the tropical downpour of the submerged city out of the window.’

Near future, maybe… But listening to Burial as I walk through damp and drizzly South London streets in this abortive Spring, it strikes me that the LP is very London Now – which is to say, it suggests a city haunted not only by the past but by lost futures. It seems to have less to do with a near future than with the tantalising ache of a future just out of reach.

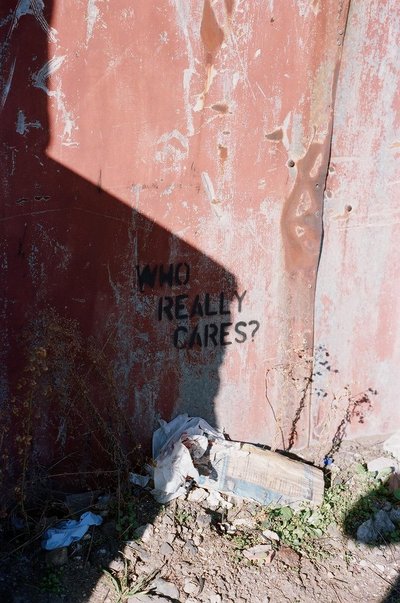

It’s interesting to compare the LP with the forthcoming EP on kin by Johnny Dark (see my press release here). Johnny’s Toronto-based ‘nu-step’ is a kind of science fictional what-if exercise; what if the late 90s London 2-step inhuman-feminine sound had continued to mutate without devolving into the sullen dead ends of grime and dubstep? The ultra-exuberance of Johnny’s sound – ‘garish rather than grimy’ – contrasts starkly with the mournful restraint of the Burial album. Instead of the ‘can’t wait’ of 2-step’s anorgasmic anticipation-plateau, Burial is haunted by what once was, what could have been, and – most keeningly – what could still happen. Johnny’s sound has all the freshness of newly sprayed graffiti; the Burial LP is like the faded ten year-old tag of a kid whose rave dreams have been crushed by a series of dead end job.

Burial is an elegy for the hardcore continuum, a Memories from the Haunted Ballroom for the rave generation. It is like walking into the abadoned spaces once carnivalized by raves and finding them returned to depopulated dereliction. Muted air horns flare like the ghosts of raves past. Broken glass cracks underfoot. MDMA flashbacks bring London to unlife in the way that hallucinogens brought demons crawling out of the subways in Jacob’s Ladder‘s New York. Audio hallucinations transform the city’s rhythms into inorganic beings, more dejected than malign. You see faces in the clouds and hear voices in the crackle. What you momentarily thought was muffled bass turns out only to be the rumbling of tube trains.

Burial‘s mourning and melancholia sets it apart from dubstep’s emotional autism and austerity. My problem with dubstep has been that in constituting dub as a positive entity, with no relation to the Song or to Pop, it has too often missed the spectrality wrought by dub’s subtraction-in-process. The emptying out has tended to produce not space but an oppressive, claustrophobic flatness. If, by contrast, Burial’s schizophonic hauntology has a 3D depth of field it is in part because of the way it grants a privileged role to voices under erasure, returning to dub’s phono-decrentism. (Penman again – Dub ‘makes of the Voice not a self-possession but a dispossession – a “re” possession by the studio, detoured through the hidden circuits of the recording console.’) Snatches of plaintive vocal skitter through the tracks like fragments of abandoned love letters blowing through streets blighted by an unnamed catastrophe. The effect is as heartbreakingly poignant as the long tracking shot in Tarkovsky’s Stalker that lingers over sublime objects-become trash.

Burial‘s London is a wounded city, populated by ectsasy casualties on day release from psychiatric units, disappointed lovers on night buses, parents who can’t quite bring themselves to sell their rave 12 inches at a carboot sale, all of them with haunted looks on their faces, but also haunting their interpassively nihilist kids with the thought that things weren’t always like this. The sadness in the Dem 2 meets Vini Reilly-era Durutti Column ‘You Hurt Me’ and ‘Gutted’ is almost overwhelming. ‘Southern Comfort’ only deadens the pain. Ravers have become deadbeats, and Burial’s beats are accordingly undead – like the tik-tok of an off-kilter metronome in an abandoned Silent Hill school, the klak-klak of graffiti-splashed ghost trains idling in sidings. 10 years ago, Kodwo compared the ‘harsh, roaring noise’ of No U-Turn’s ‘hoover bass’ with like the sound of a thousand car alarms going off simultaneously’. The subdued bass on Burial is the spectral echo of a roar, burned-out cars remembering the noise they once made.

Burial reminds me, actually, of paintings by Nigel Cooke currently on show, appropriately enough, at the South London Gallery in Camberwell. I’ll be writing more about Cooke’s paintings over the next few days, but the morose figures Cooke graffitis onto his own paintings are perfect visual analogues for Burial’s sound. A decade ago, jungle and hip hop invoked devils, demons and angels. Burial’s sound , however, summons the ‘chain-smoking plants and sobbing vegetables’ that sigh longingly in Cooke’s painting. Speaking at the Tate last week, Cooke observed that much of the violence of grafitti comes from its velocity. There’s something of an affinity between the way that Cooke re-creates grafitti in the ‘slow’ medium of oil paints and the way in which Burial submerge (dubmerge?) rave’s hyperkinesis in a stately melancholia.

Burial‘s dilapidated Afro NoFuturism does for London in the 00s what Wu Tang did for New York in the 90s. It delivers what Massive Attack promised but never really achieved. It’s everything that Goldie’s Timeless ought to have been. It’s the Dub City counterpart to Luomo’s Vocalcity. Imagine a spectralized Gorrilaz on downers, but a tenth as smug and ten times as evocative. Burial is one of the albums of the decade. Trust me.

[…] of this memory that itself is a re-sounding, I’d only be transposing Mark Fisher’s embrace of Burial into another time, another place. Which is precisely Fisher’s point. If I were to […]

[…] (原文收錄於Mark Fisher¹的個人博客『k-punk』 於2006 年發表的網誌: https://k-punk.org/london-after-the-rave/) […]