I’d rather Fleetwood Mac…

Tue. June 29, 2004Categories: Abstract Dynamics

[Prefatory note: Ive been preparing this post for a while, cultivating an obsession you might say, but putting it up now might be regarded as perverse if not to say self-defeating timing, since it seems to contradict the burn-all-nostalgia, the past-is-dead message of yesterdays Glastonbury fulminations. Only superficially, though. What irritates and irks about Glastonbury is what irritates and irks about students and Indie (for it is their festival, the celebration of their culture): namely, that it occupies a position of alleged marginality only to clog it full of what is most horribly mainstream and moribund*. Far more interesting to do the reverse to occupy the mainstream and redirect, deflect and infect it. OK, OK, this sounds like entryism, and we know how discredited that philosophy is, right? But if youre not persuaded by me, listen to Greil Marcus: With its insistence on perceptions snatched out of a blur, drawing on (but never imitating) Jamaican dub and ancient Appalachian ballads, Fleetwood Mac is subverting the music from the inside out, very much like one of John Le Carres moles who, planted in the heart of the establishment, does not begin his secret campaign of sabotage and betrayal until everyone has gotten used to him, and takes him for granted. (Fever in the Marketplace: Real Life Rock Top Ten 1979, In the Fascist Bathroom, 82-83]

We like Le Carre comparisons here

I love Fleetwood Mac in the way that you love those things that you come to late in life.

Being born in the late sixties and coming to pop awareness in the early eighties meant that my first taste of F M was the singles from Tango in the Night (1987), easily dismissed at the time as appealing enough but emollient, depthless MOR confections. The only trace of the preposterously successful Rumours (1977) by then was the instrumental section of The Chain used as the theme tune for the BBCs motor racing coverage. (Later, Id encounter Go Your Own Way when Scorsese used it in Casino.)

In America, it could not but be different. Rumours cast a vast shadow over US rock and pop that would be inescapable for a generation.

Fleetwood Mac, Simon wrote in his 1994 piece on Tusk were what America had instead of punk. In their own ways, both Rumours and Never Mind the Bollocks were about saying goodbye to the past: but where the Pistols adopted a scorched earth policy, carpet bombing the whole of rock history (even it, to Lydons chagrin, they were unable to escape it), Fleetwood Mac favoured reinvention, the painful exploration of wounds old and new, a kind of gestalt therapy that would require decades of working through. Compare Rottens No Future with McVies Dont stop/ thinking about tomorrow for a snapshot of the differences between US and UK rock in the late seventies (and between American and British psychology in general). Dont Stop had exactly the kind of message that a shellshocked America, dragging itself out of the mire of Vietnam, was ready to hear, just as the dispossessed of Callaghans Britain, stumbling towards the Winter of Discontent, took a fatalistic delight in Rottens incendiary nihilism. (Bill Clinton would famously use Dont Stop as the talismanic theme-tune for another would-be American renewal, in his election campaign of1992 but dont let the patronage of that lying sleaze put you off, please.)

American pop is slow to change but essentially progressive. By contrast, British pop, fuelled by speed and e, moves in fits and starts, breaks and loops, sudden surges, depressive longeurs and doublings-back. Thats why the US could never produce nor properly appreciate Oasis. And why the UK wouldnt nurture a band like the Nicks-Buckingham version of Fleetwood Mac.

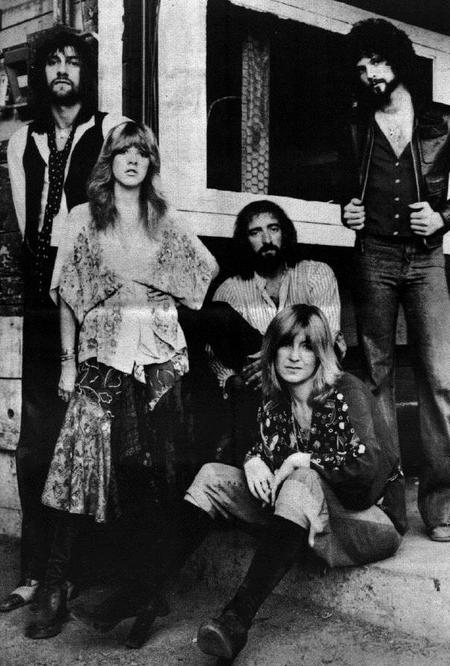

The groundwork for Rumours was laid on the self-titled album of two years before. The roles were already established. Of the three songwriters, Christine McVie, along with the rhythm section of then-husband John and Mick Fleetwood, was the link to the bands past. She was the reliable provider of bankable melodic pop, Macs McCartney. But the future lay with the two young Americans recruited to resuscitate the flatlining ex-pat Brit blues band, Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks. Buckingham, whose compositions bookend the album, brought angst, anger and a fierce, combustible energy. Monday Morning looks ahead with an unsteady gaze, unable to convince itself that the easiness of mind that it pines for could ever be achieved. The troubled waters of So Afraid roil with unresolved anxieties. But its Nicks who is the most sublimely, uncannily fascinating.

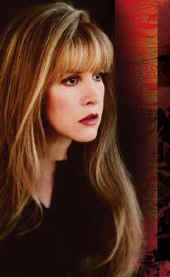

Stevies preoccupations are easily caricatured. Yet for all her rep as an ethereal, dippy hippie, Nicks femysticism is surprisingly material: her becomings-woman – always associated with physical instantiations (storms, oceans, birds) – invariably pass by way of becomings-animal to becoming-the-cosmos. The entity she invokes is less the Mother Earth of traditional feminine symbolism (whether on loan from the male imaginary or reappropriated by feminists) than what Can called Mother Sky, the great cosmic seducer who lures you into flight rather than roots you to the ground.

Rhiannon is her first anthem to this elusive, forever fugitive agent of female flux. The song – a paean to she who cannot be pinned down or defined, the temptress who rules her life like a bird in flight – could be the female reply to The Stones Ruby Tuesday. Nicks renders it as a gentle taunt to Rhiannons male pursuers, those who would own or possess her: Will you ever win? Landslide, elemental and occasionally elliptical, is an achingly pretty rumination on passing time. It auditions what might be called Nicks Space-Country sound. (Its no surprise that, when it was covered by a the Dixie Chicks last year, Stevie won a Country award.)

Nicks poised female strength (in song, if not in life) couldnt form a greater contrast with Mcvies recorded persona. Christines reputation as the bands sensible member is undeserved. On the contrary, Mcvies songs express a submissiveness so consistent as to be almost pathologically masochistic. Say That You Love Me, Christines Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?, boasts one of her most winning melodies, but it speaks of distrust and betrayal. The impending-end-of-the-McVie-marriage song, Over My Head, is painfully equivocal, not sure whether it wants to continue drowning in what sounds like an abusive subordination to the Other (It sure feels good) or come up for air (am I wasting my time).

But Fleetwood Mac is only the prelude to Rumours, which, from its first seconds, feels epochal. No need to dwell on the soap operas which attended its production, the final disintegration of the McVie marriage and the descent into acrimony of the Nicks-Buckingham affair, because that story has been endlessly told, nowhere better than on the blood-letting catharsis of the songs themselves.

The Chain, credited to the whole band, is the core around which the rest of the album grows; its central image calls up all the contradictions and compromises of their complexly intertwined dependencies and co-dependencies: bondage and fellowship, bondage as fellowship, fellowship as bondage.

McVie provides the joy (the solo-piano epiphany of Songbird, the giddy first-flush butterfly flutters of You Make Loving Fun and that ageless tribute to optimism, Dont Stop), but the catalytic core of the album is the dialogue between Buckingham and Nicks.

Go Your Own Way is the sound of Buckingham warring within himself, alternately placating then damning his lovers phantasmatic image, the verses supplicative (If I could/ I would give you my world), the chorus subsiding into desperate anger, the song lurching between Ill love you forever and fuck you, its over before finally incandescing in an (instrumental) ecstasy of rage. I (dont) want you back.

Stevies Dreams responds not with anger, not even reproach, but anticipates the lover becoming snared in his own rueful memories which are destined to give the lie to any cheap conquests he might temporarily enjoy (Women they will come and they will go/ But when the rain washes you clean, youll know.)

The track Im continually drawn back, though, to is the closer, Nicks Gold Dust Woman. Its an ending to an album as suspended, as poised, as the dying shimmer of Roxy Musics For Your Pleasure. An eerily, ironically prophetic future autobiography of Nicks addictions (first, to cocaine and later to prescription tranquillizers: rock on gold dust woman/ take your silver spoon/ and dig your grave), the track wouldnt be out of place on Tago Mago. The Gold Dust Woman, a dragon, a spider, is the female anti-type to Rhiannon: imprisoned and imprisoning, quite literally a femme fatale, a life-denier rather than a fleeing free spirit.

Rumours is, for better or worse, emblematic of its time, unable to escape the seventies it so effectively soundtracks. Its successor, Tusk (1979), however, is untimely, impossibly intimate and unassimilably eccentric, largely because of Buckinghams megalomaniac production, which, in addition to giving the whole album a 3D hypervividness, made it a genre-of-one unrepeatable singularity.

Tusk includes some of McVies most alluring if less immediate songs: the opener, Over and Over, its lovely, lazy groove, offset by Lindseys slide guitar, perfectly evokes the giddying incredulity of falling in love: Could it be me? Could it really, really be?. (To which Buckinghams What Makes You Think Youre the One? might be the spiteful riposte.) Never Make Me Cry is a rarely beautiful, fragile plaint, poised, as ever, between faith and fear. But Brown Eyes, like a ballad played by Miles circa In a Silent Way, is McVies most entrancing – and entranced song – an eddying, swirlpool of qualified rapture, stoned on the prospect of the long yearned-for love, but sobered by the memories of past betrayals.

Once again, though, it is the contrast between Nicks and Buckingham that provides the albums most compelling source of drama. Here, more even than on Rumours, the differences between male and female libidinal economies are exquisitely explored. Buckinghams compositions some of them less than two minutes in length – ejaculate to a hurried conclusion, while the typical Nicks song lingers for a good five, six minutes. Lindsey founds a bizarre microgenre with almost all of his songs, from the deranged dadaist hillbilly boogie thrash of The Ledge, Not That Funny and ‘That’s Enough for Me’ through to the gorgeous, nerve-taut Pet Sounds harmony-machines such as Thats All For Everyone and Walk a Thin Line and the howl-at-the-moon Partched blooz of the mournful Save Me a Place.

Where Buckingham burns, Stevie smoulders, surges and swell, shimmers and simmers.

Tusk showcases three of Stevies and therefore anyones – best songs. Simon said everything that needed to be said about the enigmatic Sara: Siphoning sheer nectar from her throat, Stevie is cradled in Buckingham’s shimmerscape production–cascades of scintillating acoustic guitars, susurrating plumes of angel-breath harmonies, drums that seem to billow in out and of the mix. I certainly cant do better than that!

You won’t ever hear a more powerful song about the fading afterburn of a failed relationship than ‘Storms’. Hear it as the sequel to the Supremes Love Hangover. If Love Hangover is about the immediate shock of rejection, about the literal inability to accept that its over, about a willing indulgence in the negative ecstasy of pain, Storms is about the moment when denial is no longer possible, when the endorphin rush gives way to a numbness, when your bodys no longer able to cry, when you have to take the first step towards on that always ghastly journey, moving on. Every night that goes between/ I feel a little less

Beautiful Child is the third in this incredible triptych. As so often with Stevie, it’s elliptical, elusive, but evocative. Its images and affects seem to lock in directly to the unconscious. The song appears to be about a slow-smouldering love affair (‘you fell in love when I was only ten’) – well, less an affair than a kind of fated betrothal, a Heathcliff and Cathy lifemeld, now ended – seemingly forever (because of death?) Musically, it’s like a clockwork-machine gone awry (Simon: ‘The effect is like the heart is literally broken, a clockwork device gone out of synch’), a staggeringly beautiful paean to regret and loss, Stevie’s multi-tracked vocal haunting itself…

These three songs suspend rock’s blues-derived, male-modelled, tension-release ‘testicular thermodynamics’ to explore a slow-burn series of plateaus.

Leaving aside the forgettable Mirage, FMs next most significant moment was 1987s Tango in the Night, the album that Buckingham rescued from the bands coked out indifference, at the cost of his own departure. By this time, Stevie was the furthest gone, a catatonic zombie wheeled into the studio to perform her contributions. And she sounds like that, autopiloting through the meandering AOR doodles of Seven Wonders and Welcome to the Room

Sara. McVie contributes two of the albums mega-hits; the Afropop effervescence of Everywhere, and, one of her most disturbing hymns to supplication, Little Lies . But the highlight, appropriately, belongs to Buckingham; his Big Love sounds like the copulation of Duchampian desiring machines. Marcello is right to invoke Horn and ZTT, though for me, the album displays many of Horns vices, an uninvolving, pristine monumentalism, cavernous and vacuous.

Finally, then, to the MTV/VH-1 comeback special from 1997, The Dance.

Watching, you can feel all the electricity thats lacking at Glastonbury crackle. Its a masterclass in rock performance which doesnt mean histrionic posturing (Bono), end of the pier metamugging (Robbie) or tonsil-rupturing vocal gymnastics (Xtina).

Theres something almost intangible but immediately palpable that separates, say, Macca at Glastonbury from The Dance. Macca hits all the notes and technically performs well. But what FM do that McCartney didnt happens between the notes. Its the difference between acting and acting out. On The Dance, Fleetwood Mac occupy the affective space of the songs, they dont simply play them. They enter into a performance trance. The result is that every song matters.

Everything is dramatic, including the bands arrangement on stage.

At the back, the groups engine room, itself a study in contrasts. Mick Fleetwood, effusive, gregarious, an attention-junkie, gurns, leers and lurches like some hyperactive Ray Harryhausen-giant, while John McVie, baseball gap pulled down over his eyes, lurks in the shadows in the manner of unassuming mechanic. On the right, slightly detached, vaguely inhibited, uncomfortably stiff, dressed like a glamorous headmistress, Christine McVie: sensible and sentimental. But the real action is front and left. Stevie, leaning forward in a witchy hunch, swathed in shawls and scarves, sensuality incarnate, her gaze fixated, for most of the time, on Buckingham (body taut, his head rolled back), both well aware that the source of the groups sorcerous power is the interplay between the two of them.

Live, Buckingham is the revelation. Sure, by now he can play Stevies courtly suitor to perfection (check his attentive acoustic picking on Landslide), but he comes into his own on songs like My Little Demon, So Afraid and Go Insane where he stakes his claim to be considered the inheritor of howling, anguished bluesman, tradition initiated by Robert Johnson. Imagine Led Zeppelin if they were good; i.e. with all the nihilibidinal anguish, but minus Plants caterwauling histrionics or Pages overelaboration (errr, whats left?) And look at what he does to Tango in the Nights Big Love. Scrabbling it out solo on an acoustic guitar, he strips the songs surface gloss away to reveal a raw, bleeding core of blues anguish and failed ambition.

Once again, though, its the luminescent Nicks who is the stunning eye of the storm. Shes grown into Landslide, a song which sounded too old for a woman in her twenties. As she sings the line, ‘Ive grown older, too’, she gives a wistful, knowing shrug

.. But it’s Silver Springs, the song criminally left off Rumours for ‘lack of space’, that is the highlight of the DVD. Stevie shows that she could out Alanis Alanis twenty years before Jagged Little Pill. She tries to sound graceful and in control, if regretful (‘Is she pretty? … Was it worth it? … I don’t wanna know’), when out of nowhere, the song is swept up by a tempest of raw emotion, Stevie transformed into a harpie-banshee agent of revenge and implacable obsession – ‘Time casts its spell on you/ But you won’t forget me… You’ll never get away from the woman who loves you… Words are just a fool.’ She has always been a storm, indeed, and like the X-Woman, she is superbly impressive at marshalling and controlling her elemental power.

IF YOURE EVER GOING TO BUY A DVD OF LIVE MUSIC, BUY THIS ONE

I’ve not yet organized my thoughts on last year’s comeback LP,

‘Say You Will’, but you should definitely read Marcello’s thoughts on it.

While we’re at it, Marcello’s general FM overview is indispensable, as his (at least I assume it’s his) Uncut review of the Redux re-releases of Fleetwood Mac, Rumours and Tusk.

* Bathetic footnote: the word moribund will always remind me of Alan Partridge onKnowing Me, Knowing You, countering accusations that its moribund with a (scarcely credible) positive assessment. Not my words. The words of Mike Taylor of TV Quick.

jesus you really DO like f.Mac. They are cool,never been a doubt in my mind – ever! They can make me cry and smile. Never to be “underestimated or understated” -I say.

Yeh, as I say, they’re relatively new to me — something that’s crept up on me on the last two/ three years.

That Dance DVD really is the shit…

I’d rather Jack…

Good stuff Mark. We’ve been absolutely caning the FM reissues in the office- although the eponymous album isn’t nearly as strong as the others. Especially wonderful was the demo version of Second Hand News, which I swear is one of the perkiest yet profoundest things known to man.

I also think Tango is patchily brilliant. The guitars sound incredibly pristine, to a similar degree of tone-festishism as Chris Isaak’s Wicked Game say. In the era of Stock Aitken and Waterman, pop bands had to try and smuggle the guitar in again, sounding almost as pure as a synth. Big Love is an amazing tune- I heard a re-edit of it into a deep-house / disco tune which worked superbly, taking those swelling, throbbing drums (Freudianisms definitely intended) and making a floor quaker out of it.

Derek, yeh TITN may grow on me, Big Love is fantastic.

I think you’re being hard on the 75 album – it does include Landslide and Rhiannon after all, and So Afraid, and some really nice Christine songs (Over My Head, Say that you Love me).

Know what you mean abt hammering them (as you can see), they become like a self-sufficient universe don’t they?

Yeah exactly, it’s a little world of it’s own. A world where “soft rock” suddenly started sounding very, very hard indeed. The problem with the 75 effort is that the tracks sound too different, like they hadn’t matured this new AOR style into anything fluent.

Lindsay Buckingham is fascinating I think. He manages to trade backing vocals with the girls with touchy feely casualness, yet retains an incredibly dynamic masculinity on the album (“let me do my stuff…”). That’s why it’s such an emotionally abrasive- it’s not the sound of boys doing their thing alone, it’s a competition to see who out of the men and women can do their stuff….