BUILDING WORLDS

Thu. March 18, 2004Categories: Abstract Dynamics

The more I’ve thought about this, it occurs to me that as long as there’s been a world we have been creating an imaginary counterpart to that world with different places, different people, different history, and to some degree that phantom world of the imagination has co-existed with our own.”

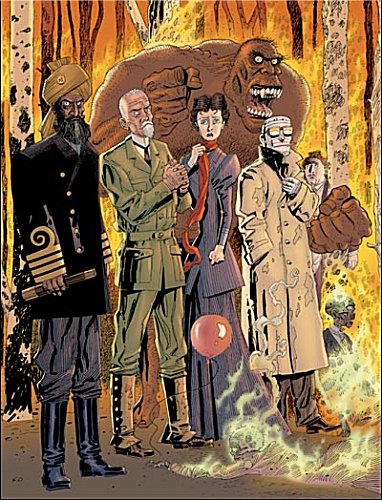

So I watched The League of Gentlemen on video at the weekend. Its a passable enough romp, if no masterpiece. More intriguing than either the film or the graphic novel upon which it is based (O.K.: Ill level with you, Ive only read the second volume of the g-novel) is its premise. Im sure everyones familiar with Alan Moores conceit: the wheeze being to combine characters from a number of late-Victorian fictions Mina Murray from Stokers Dracula, Jeckyll and Hyde from Stephensons novella, Captain Nem from Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, the eponymous hero of Wells The Invisible Man, H. Rider Haggards Allan Quatermaine, Conan-Doyles Moriarty and (in the film alone) Wildes Dorian Gray.

Idle googling after watching the film turned up this fascinating article by Peter Sanderson. Sanderson shows that Moores aim was an exploration of the origins of the 20C superhero concept in certain archetypes of Victorian fantastic fiction. Moore makes parallels between the iconography and concepts of the superhero comic and those of his simulated nineteenth century world. The name, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, for instance, was conceived of as a kind of pre-echo of DCs Justice League of America and of Marvels X-Men. (Hence the marketing of the movie as a Victorian X-Men.) In addition, Moores re-imagining of the Edward Hyde character as an enormously-proportioned brute with superhuman strength in other words as a kind of 19C Hulk was an allusion to Stan Lees well-known claim that the Hulk = Jeckyll and Hyde + Frankensteins Monster.

Moores ambition extended beyond a genealogy of the superhero, though, and embraced broader questions about the relationship between fiction and reality. Moores contention is that the construction of mythical systems is as old as the species itself, and, in the second volume of the g-novel, he includes an absurdly compendious Travelers Almanac which incorporates and interweaves Moores own retellings and appropriations of fictional characters into a grand cartographic survey of the worlds mythologies.

Sanderson demonstrates that Moores methodology is nothing new, finding parallels for this appropriative implexing (or enfolding) in such august sources as Dante and Virgil (remembering of course that Dante famously implexed Virgil into his own mythscape). A more recent analogue is Philip Jose Farmer, whose Wold Newtons fictions retold the stories of Doc Savage, Tarzan, Sherlock Holmes, amongst many others. Farmers idea was that a meteor hit a small English village in 1795, causing mutations in the gene-line which ultimately result in these heroes. (cf also Marvels Conspiracy mini-series, which cheekily suggested that the whole pantheon of Silver Age Marvel heroes were the results of US government experiments with radiation.)

Sanderson identifies that what was unique about 60s Marvel was that it projected a consistent universe. In the years prior to Marvels arrival, DC which trumpets itself as the original universe had in fact failed to cotton on to the possibilities of creating a plane of consistency connecting all their books. Marvels titles, on the other hand, were from the start envisaged as an interconnected rhizome, presided over by the omniscient creator-writer-editor Stan Lee (with footnotes – which, as per my last Marvel piece, added to the frustration of the Brit reader: i.e. see Defenders 14 which you knew very well that you would never see. But thats another story.)

Were approaching the mechanics of Pulp Theology. Pulp is above all about the production of universes . Not parallel universes, but universes which establish a plane of consistency between their fictional world, our world and previous fictional worlds/ mythologies. Compare for instance Marvels use of Dracula, Frankensteins Monster, Norse mythology (Thor). Consistency is a crucial dimension of what fascinates about Pulp. Whereas the artist-author insists on repeated acts of new creation, building worlds anew with each fiction, the pulp author supplements and elaborates upon the same mythscape,. With each additional fiction, the mythwolrd becomes more and more independent, attains an autonomy from its supposed creator. It is as if at a certain point the unconscious refuses to accept the unreality of the characters and the world to which they belong. (No negation in the unconscious according to Freud, remember). As these worlds become more autonomous, have more reality invested in them by their readers, they cease to be the exclusive product of their supposed creators. It is for this reason that authors are often uneasy about the production of such world; Stephen Kings The Dark Half and Misery and Peter Straubs Mr X give an insight into the disquiet and distaste mass market authors can have for readers who take their fictions too seriously.

King can be contrasted with Lovecraft who, like Marvel, constructed a consistent universe across his fictions. It is not so much the power of Lovecrafts lurid descriptions which give rise to the sense of reality his fictional world acquires; it is the sheer fact of his universes consistency. Erik Davis points to this in a brilliant piece on Lovecraft, :

‘Though Lovecraft broke with classic fantasy, he gave his Mythos density and depth by building a shared world to house his disparate tales. The Mythos stories all share a liminal map that weaves fictional placeslike Arkham, Dunwich, and Miskatonic University into the New England landscape; they also refer to a common body of entities and forbidden books. A relatively common feature in fantasy fiction, these metafictional techniques create the sense that Lovecraft’s Mythos lies beyond each individual tales, hovering in a dimension halfway between fantasy and the real.

Lovecraft did not just tell taleshe built a world.’

Davis calls Lovecrafts approach magick realism, although with due deference to Angus objections to this genre I should point out that he distinguishes Lovecrafts fiction from that of authors like Allende and Marquez. Whereas Marquez and Allende dust conventional realism with a patina of the Fantastic, Lovecrafts tales had a more literal magical dimension. Davis: Many magicians and occultists have taken up his Mythos as source material for their practice. Drawn from the darker regions of the esoteric countercultureThelema and Satanism and Chaos magicthese Lovecraftian mages actively seek to generate the terrifying and atavistic encounters that Lovecraft’s protagonists stumble into compulsively, blindly or against their will.

Naturally, Lovecrafts world depends for its unliving vitality upon being taken for real by fans. The word “fan”, Davis identifies, comes from fanaticus, an ancient term for a temple devotee, and Lovecraft fans exhibit the unflagging devotion, fetishism and sectarian debates that have characterized popular religious cults throughout the ages.

It is this fanaticism that so troubles some authors. Straubs Mr X, by the way, is about a reader who Straub implies idiotically refuses to accept the supposed unreality of Lovecrafts fictional cosmos. Compare this with John Carpenters masterpiece, In the Mouth of Madness. The film is itself a hyper-commentary on Pulp, in which writer Sutter Cane (a thinly-veiled King-Lovecraft composite) acts as the conduit for an invasion and contamination of our world. The invasion is not supernatural, but ontological. In a textual analogue to the Videodrome signal in Cronenbergs film (one of countless Horror references in ITMMM), Canes novels weaken their readers hold on this reality, preparing the way for the return of the Old Ones. Cane ultimately comes to the realization that his fictions were retro-engineered by the Old Ones as a means off ensuring their return. I thought I was making it up, but they were telling me what to write. Cane explicitly compares his fictions to religion, but concludes that no-one ever believed religion enough to make it work. The relation between Pulp and religion is, after all, more a matter of cultural policing mechanisms than it is a reflection of their substantive content. PKD demonstrated time and again that the distinction between pulp fiction and Gnostic revelation was an optical illusion, and what could be a better demonstration of the interchangability of cheap SF and religion than the career of L Ron Hubbard and scientology?

This interestingly connects up with the mp3 debate currently raging in the comments below because in many ways the cost of producing a universe is that your characters become public property. (Marvels own fierce protection of its own copyrights perhaps belies this somewhat; I never really understood how Wu Tang got away with their outrageous but brilliant appropriation of Marvel memes). Moores very ability to incorporate a range of characters from different authors into his League presupposes that these characters have entered the public domain. Such fictions gain reality by being dissociated from a single author, by being collectivized. Again, both Lovecraft and Marvel are models here Lovecraft famously encouraged other writers like August Derleth and Clark Ashton-Smith to contribute to his cosmos, and this process continued posthumously when the likes of Brian Lumley and Ramsey Campbell starting producing their own additions to the Cthullhu mythos.

Enough, for now.

This post is very potential for further discussions. Thanks. Have you ever explored Mesopotamian and especially Persian mythologies which I think (along with African mythologies) influenced Lovecrafts divination of hyperstitional dynamics flowing from the old ones to his books and back into the heart of their starry ancientness? What actually you said about Sutter Cane and his books playing the role of retro-engineers in their obscene communication with the Old Ones fascinates me: the pulp-horror writer is more a necromancer, the one who exhumes rather than the one who modernizes the ancient horrors since exhumation (call it a perverse ungrounding process: ex + humus: ground) proliferates surfaces through each other (scarring cold and hot surfaces of a grave), introducing architectures to speeds of becoming — becoming hot, becoming cold, being revolutionized by the dead and in the end becoming the indubitable cold; it transmutes architectures into excessive scarring processes (fibrosis … fibroproliferation of surfaces) rendering off (colding them) the solid economy of membranes, of tissues and surfaces, engineering a mess whose dimensionality blurs not to the point of a fading-out terminus but to vermicular defunct coils of dimensions which cannot resist what crawls in and out (The Old Ones); they cannot keep on negating each other any longer: ( )holes, ( )holes, ( )holes, ( )holes (but not holes) with liquidated and now evaporating Ws. Exhumation (even as disinterring or digging up [the dead?]) is not a contemporizing or a cold and inhuman modernizing operation over the things grounded (the dead?) but it is a process introducing qualitative collapse into surfaces and the facial affordances (or the stratified events) to crack them open not on the politico-economic chronosphere of Now but now as where like the role that Moby Dick (The White One) holds to seduce Ahabs becomings to untrodden Eons and Spaces. Through exhumation everything is composed the plague of Anonymous-until-Now. Anonymous-until-Now is the chemistry of the earth as the Infected One, the Forgotten One, and the Infested One; all three diagramming the earth as an unreported plague whose epidemic creativity is compassionate for all aspects of survival economy and even the Earths Zero-engine. Anonymous-until-Now and Tellurian Insurgency narrate the perversions of the Earth as an immense ungrounded becoming, A New Earth for A New People, A Good Meal for the Old Ones. Lovecraft and his fictional avatar Sutter Cane both conceived writing as exhumation where writing is actually an AWAKENING PROJECT for the Old Ones, a telluric insurgency (or according to Lovecraft, A holocaust of freedom).

Sorry for this very long and vague comment with lots of references to articles at cold-me website.

Or exhumation is a perverse modernization process?

mark, I’m not at all being facetious when I say I’m looking forward to your very long book/film/TV series/special features DVD on hyperstition and related matters, please don’t let its secrets die with you! This is wonderful, among other things a great defence of the potency and importance of those childhood microworlds which the reality principle banishes (am i right in thinking this rush of positivity was brought on by your doing some indepth comics ‘research’ ;). And I wish I had time to write an vaguely sufficient comment at the moment (however the virtues of keeping it short oughtn’t to be underrated ;)…but in the interim, have you seen the Alan Moore interview at The Edge magazine (link from undercurrent) where he talks about being possessed by supernatural entities etc.?

btw:this

>footnotes – which, as per my last Marvel piece, >added to the frustration of the Brit reader: >i.e. see Defenders 14 which you knew very >well that you would never see.

almost brought tears to my eyes!

great stuff mark! i think about this a lot too. i love the idea of each book building on an already established universe although my reference points are more like, er, tintin, raymond chandler and rex stout than marvel and lovecraft.

history books are much the same as it goes, that’s how i like to read them anyway.

Yeah! Tintin!! 🙂 🙂 🙂

The big shadow-influence on the Moore of LoG is surely Moorcock, from his reinvention of the Burroughs Mars stories, through the Oswald Bastable books (victoriana, hightech, ubermen) to Dancers at the End of Time. To say nothing of the concept of an Eternal Champion.

Like your blog, found via woebot (even though woebot’s link to you doesn’t work). I was diligent and figured out how to find you anyway. What devotion, eh? Actually, I’m just a sucker with any website with “punk” in the name or addy.

Peace!

Andrew C

What you’re describing actually reminds me a lot of the situation of TV shows that choose to have a consistent “universe.” In the case of some shows, especially sitcoms, this isn’t much of a problem, since the universe is basically the main characters and their relatives, with any new characters basically disappearing after the episode they’re in. But for some shows (the Simpsons and Buffy spring specifically to mind) which choose to be more expansive and are dealt with by a multiplicity of writers, they face a really interesting challenge–shared by comics, I think–of how to play with that universe without getting too caught up in the minutae of it all, as I think the new Star Wars films have. (And that’s sort of why I stopped watching the X-Files.) Maybe I’m erring here by talking too much about TV shows with their roots in sci-fi/fantasy; it’s just easier there. I think the Simpsons is a perfect example. People have complained about them getting worse and worse as time goes on, but I think what actually happened is that they ran up against the limits of plots and characterization available to sitcoms and started exploring surrealism, pure comedy, intertextuality, etc. Which strikes us as weird, but which can also be immensely pleasing. It’s interesting when comics do this, too.

Reza, yr post is stupefyingly, densely brilliant… Maybe we could unpack some of this at a more uh leisurely pace. And thanks for yr kind words about k-p…

Robin, I blush. And yes, some, in-depth ‘research’ has been done. Tho not enough! Haven’t checked out the Moore interview from the Edge, but did read lots of the Moorcock stuff, which brings me to….

Jim, yeh, I was going to mention Moorcock/ Jerry Cornelius in the piece, but it was already sprawling out of control as it was. Tho behind both Moorcock and Moore is Wells (the major presence in the Bastable novels and in the Dancers at the End of Time).

Andrew, glad to have you aboard, thanks for the dedication. (Think the link on the woebot sidebar works, even though yep there’s one http too many in the link in the blog round-up post).

Sorry Mark for the hurried style (yes, Id like to unlock its coded protocols) … am currently busy with preparations for the Persian New Year (btw: Happy Persian New Year). And some corrections:

Through exhumation everything is composed as the plague of Anonymous-until-Now

…whose epidemic creativity is uncompassionate for all aspects of survival economy and even the Earths Zero-engine.