ART POP, NO, REALLY

Mon. July 5, 2004Categories: Abstract Dynamics

If were going to discuss art pop, we really ought to forget Franz Ferdinand and Scissor Sisters and talk about Moloko.

I saw them last night at the otherwise desultory Common Ground festival in Clapham, an event whose line-up was as limp as its name was uninspired.

Gratifyingly, by the way, Common Ground wasted no time in confirming all my prejudices about festivals (and then some): those on the stage haplessly attempted to muster some enthusiasm from bored punters, who wandered around listlessly in a sunlight inimical to pops mystique, Strongbow in their hand, kid on their shoulder. We werent the only people to sit and read the paper for a while.

The bill was shocking. It felt like a local council free event, the organizers under the lamentable misapprehension that theyll appear with it by booking dance acts such as the oppressively lumpen stodge of Freestylers (a candidate for my worst band ever, actually; I mean, at least the Stereophonics dont taint rap and dancehall by association) and the Dub Pistols. These cloddish white appropriations of hip-hop, drum n bass and dancehall are dis-spiritingly, missing-the-point funkless and morosely male (even when they use female vocalists). If their diabolic intent was to systematically convert some of the most exciting, cutting-edge music of recent years into a dull migraine thud, they couldnt have done a more ruthlessly efficient job.

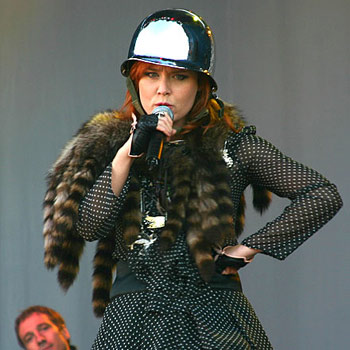

And then Moloko arrived, Rosin, preposterously but marvellously, in a helmet, like Boudicca come to retake London.

Roisin is every inch the pop star. Pop stars are a rare breed at the best of times but theyre scarce to the point of near-extinction now. (There are more pop singers and celebrities than you can stick at, of course

) Its partly a question of style, partly of glamour, but mostly its to do with charisma.

In its original meaning, charisma meant a gift from God. Appropriate. For charisma is dispensed according to fates inegalitarian whim. Roisin has it. No amount of bluster, sweat or sinew will allow the likes of the Freestylers to acquire it, even though the resentful, leveling spirit of the times would have it otherwise.

So Roisin arrives and you can feel the change in the air. Where before the stage was a libido-draining vortex (DJs on stage just one question: why?), now it radiates energy, excitement and electricity. Charisma, its almost a physical thing.

Roisin has a glamour which includes sexual attractiveness but it is not reducible to it. Glamour originally meant a spell cast by women to entrance men Roisin is certainly capitivating, but not only to men.

If (viz Foucault) sex is ubiquitous and compulsory, glamour is now subtly forbidden. With the Baudrillard of Seduction, a book which could serve as a bible of glam, we could even see sex – in all its directness, in all its supposed lack of concealment – as a way of warding off glamours ambivalence.

Much more successfully than derivative dullards like the thankfully now forgotten dull-as-a carpark-in-Croydon Suede, Moloko reconnect with the glam discontinuum which was ostensibly terminated by acid houses equity culture in the late eighties. Glam also had a terminator of an entirely different nature: hip hops in-equity culture of conspicuous bling, one of the most unfortunate side-effects of which has been the rise of sportswear (surely one of the most depressing sights now, and not only because of its implied menace: a group of male teenagers dressed in tracksuits and hoods).

That quotidian functionalism is todays equivalent of the agrarian organicism from which Seventies glam revolted into style. Glam repudiated hippies nature in the name of artifice; disdained its fugged, bleary vision of equality for a Nietzschean-aristocratic insistence upon hierarchy; rejected its unscrubbed beardiness in order to cultivate Image. (Image and great pop are indissoluble. Maybe the integral role of Image is what separates Pop from folk. Certainly, art pop, from Roxy to Jones to the New Romantics, is unthinkable outside fashion.)

Madonna carried traces of the glam aesthetic over into the pop mainstream in the eighties, but a more obvious precursor for Roisin is Grace Jones (about whom k-punk must write extensively in the very near future). Like art poppers such as Bryan Ferry (whose Love is the Drug she famously vamped), Jones take on pop was essentially conceptual; at the same time, she knew that concepts without sensual instantiation are as worthless in pop as they are in art (a lesson some of our contemporary artists would do well to heed). Incidentally, an appreciation of the concept is one of the many things that Franz Ferdinand lack that was there in their inspirations. (Actually, FF are like a copy made by an alien race, which maintains all the superficial features of the original, but misses the essential).

Roisin has that paradoxical duality which comes as second nature to the compelling performer: she is both meticulously obsessed with her image and, at the same time, apparently indifferent to what she looks like. This comes over in her dancing. There is none of the over-rehearsed choreography of the Pop Idol puppet. Like Jaggers and Ferrys, Roisins movement can occasionally look ungainly and gauche. Sometimes we feel that weve caught her prancing in front of the mirror.

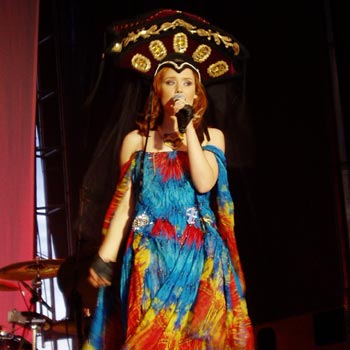

Its partly this that gives her a distance from her image that isnt camp, or at least not camp in the Kylie sense. There is an enjoyment there (this is one of many things that separates Roisin from Kylie: Kylies air hostess professionalism exudes grim determination, never enjoyment). Principally though not of course exclusively, this enjoyment is her own, an enjoyment that partly derives from being the object of attention, but which goes beyond that. Like all great performers, Roisin onstage enters a kind of performance trance, attaining the innocence of a child at play, to use Nietzsches beautifully resonant phrase. Her costume changes including fetish boots and a military cap for Pure Pleasure Seeker have the deranged playfulness of a girl riffling through a dressing-up box.

Just as Moloko give the lie to the accepted wisdom that dance music must be delivered by hooded anonymities, so they also expose the flimsiness of the alibi that Franz Ferdinand offer for indie conservatism: the idea that art pop must be retro. Molokos engagement with house and techno recalls Roxys dallyings with funk and Jones extraordinary Sly-and-Robbie assisted construction of a wonderfully elastic dubfunk. Any funk in FF is third hand, an appropriation of an appropriation.

The third shibboleth that Moloko demolish is the notion that dance music cant be performed live. If youd left before they came on, you would have gone home convinced that this was the case, as group after group trudged offstage having failed to capture the precision-engineered thrill of the rap or d n b studio production. Not so with Moloko.

For the most part the group are as reluctant to take the limelight as Roisin is delighted to bathe in it. Perhaps because of this, they are an unbelievably efficient mutagenic sonic machine, dilating tracks into anti-climactic plateaus with the same skill that a brilliant producer uses in the studio to sequence an extended version. You know youve arrived at a plateau when it feels like the track could continue indefinitely or end immediately. This happened with every track last night. No doubt this is because the songs provide such a strong basis for improvisation. Does anyone in pop at the moment, apart from maybe Destinys Child, have a sequence of high-quality singles to rival Molokos run from Sing It Back to last years Forever More? Like the Junior Boys, Molokos whole existence demonstrates that rhythmic innovation and spine-tingling songwriting do not have to be mutually exclusive. (Why did we ever think they were?)

Misleading, then, to select highlights, but the set is deftly constructed, so that the last three tracks pack the most impact: Forever More, with its anempathic house bass , Roisin plucking and shredding petals from an enormous bunch of roses as she delivered its gorgeous blues plaint; Sing It Back, which theyve expanded into a deluxe suite, a song as a sequence of different possibilities; and finally the enigmatic Indigo, which begins all Moroder-minimal, just Roisin, a drum machine and an electro throb, then builds into a mighty cake-walk riff, as brutally bass-heavy as The Fall at their most punitive.

The only drawback? Roisin said that itll be a long time until Moloko play in London again.

Damn.

they played (and I missed) a few concerts here in australia – a cross country touring dance party festival thing. apparently they were spectacular then as well and a million times better than anything else on show.

Great post, Mark!

Actually, Moloko must see themselves as continuators of the great Roxy Music tradition, since they xeroxed their “Do The Strand”/”In Every Dream Home A Heartache” promo for the “Plure Pleasure Seeker” videoclip. It was early Ferry’s wet dream: one of his muses/cover-girls as the front-woman and an Eno that doesn’t steal the spotlight.

(By the way, Mark, I couldn’t see the Spanish matchs and I’ve been absent from the blogosphere, so I didn’t had much to comment in the e-2004 blog except for calling Iñaki Saez names…)

Thanks Diego…

No problem abt the e-2004 blog; I can well appreciate why you might not be particularly motivated to post after what happened to Spain. My enthusiasm waned after England went out, too; once the Czechs were despatched, well…

Was so uninterested in the final that, as you see, I went to Moloko instead. A good choice I think…

I still have a massive soft spot for the spacefunk of “Do You Like My Tight Sweater”.

Wicked wicked wicked review Mark.

I love Moloko, they’re a fantastic band. Saw them in Sheffield a few months back and they were utterly fantastic. Shame they might well be shuffling off the coil now…

Do you like my tight sweater is just one of the most amazing, increasingly sea-sick, mutation-inducing albums ever made…

Thanks Paul…

I’m hoping that Moloko’s absence will be very temporary….