Thu. April 8, 2004

Categories: Abstract Dynamics

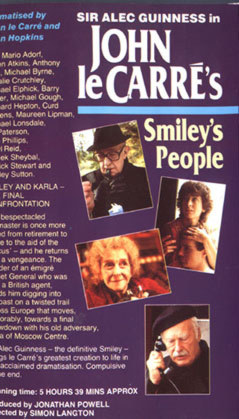

Just watched all six episodes of the BBC’s 1982 production of Le Carre’s Smiley’s People.

Smiley’s People needs to be sipped, savoured, swilled around the palate like the fine vintage it is; to be enjoyed as a cure for the attention-atrophying aphasia of Now TV’s kwick-kutting migraine. It takes its langurous but assured pace from Guinness, for whom the word ‘lugubrious’ might have been invented. After the set-up preamble in the first episode, there’s barely a frame of the drama which Guinness doesn’t dominate. But his dominance, like Smiley’s, arises from a quiet natural authority that disdains the tasteless excesses of ostentation and histrionics. Unlike Olivier, Guinness is a natural film and television actor. His understatedness, his mastery of the micro-gesture, make his performances ideally suited to the close-up; he knows he doesn’t need to bark and mug in order to project to the back row. Comparisons with the likes of shouting prancers such as Gary Oldman are so invidious that I won’t pursue them. Guinness’ well-heeled subtelty is infectious; everyone in the cast plays their part to minor-key perfection.

Narratively, Smiley’s People makes little if no sense without the background provided by Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, but, much to its credit, the adaptation doesn’t pander to audience expectations by shoehorning embarrassingly contrived recapitulations into the plot; the references to the previous serial are elliptical and oblique. The back story – Smiley’s lifelong struggle with his monkish and enigmatic double, Karla of ‘Moscow centre’; Karla’s penetration into the heart of the Secret Service/ ‘Circus’, whose total destruction is only narrowly averted by Smiley’s uncovering of Karla’s mole, Bill Haden, a partial victory which does little to assuage the professional and personal defeat effected by Haden’s affair with Smiley’s wife, Ann – emerges via offhand allusions, questions, loose threads. In any case, affectively, it’s clear what is at stake; Guinness can convey the weight of a lifetime of accreted pain, disappointment and stifled expectation in his movement across a room, in the way he wipes his spectacles . Guiness’s deflections of the constant inquiries about Ann’s wellbeing – themselves multi-levelled interrogations, combining superficial politeness with genuine concern and a salt-in-the-wound crowing at Smiley’s fatally compromised masculinity – are a masterclass in nuance.

Smiley is famously the anti-Bond; not the roue but the wronged husband, not a man of action but an expert manipulator and methodical researcher. He is the rotund, white-templed real to Bond’s eternally virile fantasy. Yet Smiley is now as much a part of the British mythscape as Bond, or Sherlock Holmes. Eternally dutiful and imperturbably patient, he is the cuckolded Arthur to Ann’s Quinevere and Bill Haden’s Launcelot, a prince in a Lacanian tragedy.

Both Tinker, Tailor and Smiley’s People are dominated by two virtual absences: Ann (Sian Phillips) and Karla (Patrick Stewart). Over the twelve hours of both serials, Karla and Ann cannot occupy more than ten minutes of screen-time between them. Karla’s role in the first serial is confined to flashback scenes of his legendary encounter with Smiley in Delhi when the British agent let the Soviet spymaster ‘slip through his fingers.’ Both serials’ le petit objet a is the cigarette lighter – a gift from Anne – Karla took from Smiley during this meeting. ‘It’s only a Ronson,’ Smiley observes, well aware of the symbolic freight that this slightest of material objects – tossed aside by Karla at the serial’s conclusion in an ilegible gesture: an acknowledgement of defeat? a sign of continuing defiance? – carries. Incredible to reflect, given his luvvy hamming as Capt. Picard, that Stewart does not say a word in either serial. But his reticence lends Karla’s rare appearances an electricity, a glowering, inscrutable intensity for which no amount of overblown speechifying could substititute.

Ironic about the possibility of restoring lost unity, of placating life’s perpetual aches, Smiley is the successful Lacanian analysand par excellence. When Karla is finally captured in Berlin, when the cigarette lighter is returned (the fort-da game temporarily at an end, the lost object back in Smiley’s grasp), Smiley’s loyal lieutenant, Peter Guillam, turns to him. ‘You’ve won, George.’

There’s more than British restraint, phlegmatic containment, behind Smiley’s reply. He’s attained a Spinozistic wisdom, an awareness ‘that there can be no hope without fear, and no fear without hope’. Far from embittering him, pain and reversal have bequeathed to Smiley an indifference to the fickle viscissitudes of outrageous fortune that is ‘philosophical’ in both the colloquial, and the rigorously Spinozistic, sense. His unflappable dispassionate calm is an end in itself.

‘Yes,’ Smiley says, ‘I suppose I have.’

I don’t have Smiley’s People, but continual re-viewing of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy DVDs is one of the things that makes life bearable.

Of course, it proves _everything_ you’ve ever said about TV being better in ye olde days.

This doesn’t add anything useful to what you’ve said of course, but I thought it deserved one comment at least!